It has long been my contention that there is no story about life on earth that does not boil down to an evolutionary story. The creationist version of life on earth has, since the 19th century, made large use of the notion of intelligent design – but anybody who knows anything about design knows that it evolves. The intelligent design argument is a mess, since the standards it uses to critique Darwinism are, of course, entirely absent when it tries to construct the meaning of intelligent design. Just as we can trace the evolution of the design of the watch by the material left behind in its wake – diagrams, tools, etc. – so too, if intelligent design were true, we would be able to see the material left behind in its wake – proto-humans, for instance. At this point, intelligent design simply gives up the intelligent part and opts for supernatural design, a design that defies the same physical laws that, on its critique side, intelligent design uses to try to de-legitimate Darwinian evolution.

Of course, creationists aren’t the only ones to ignore the evolutionary nature of all accounts of design. Philosophers, much to my distress, often assume things like zombies without having any sense that a zombie has to come with an evolutionary story, and that has to be packed into their account that a zombie doesn’t sense like a human being. This simply proves that philosophers are bad intelligent designers – something I think Wittgenstein spotted long ago.

At the same time, not all evolution is Darwinian evolution – that is, the statistical effect of selection, while definitely having some effects at the cultural level, does not play the role it plays in Darwinian evolution. Evolution on the cultural level often takes the form of assemblages that bring together different developmental paths as overlapping associations.

All of which is the wordy and way too wordy intro to what I want to do for a lark: understand the evolution of the ghost shape that one sees, in paper cutouts and cartoons, on Halloween.

Jean-Claude Schmitt, the author of Ghosts in the Middle Ages, lists six ways in which ghosts were depicted in the 13th and 14th century: the Lazarus, or resurrected man; as looking like a living person; as looking like a small, naked child, a common way of depicting the soul; wrapped in a diaphonous shroud; as a decomposing corpse; and as invisible, with the convention here depending on the text. In the last case, the text speaks of the ghost being sensed, but not seen.

It is striking how closely this list corresponds to features one finds in the common, commercial construction paper ghosts that are bought before Halloween in the store and strung up on doors and windows to create the “haunted house”.

However, in the age of drawing, painting and stonework, there were certain possibilities, mixes of the above categories, that were beyond the technological imagination. Clearly ectoplasm, that gross but fascinating presence in much of the spiritualist photography of the 19th and 20th century, is a compromise, a condensation, of the decomposing corpse and the diaphonous shroud. It was diaphonous matter in a state of decomposition. And yet, this decomposition was astonishingly lively – presaging the world of synthetics, the jello world, that came after 1945. Which was incidentally not only the year that the war gave up its ghosts, but also the year Casper the Friendly ghost was launched, a sort of Cold War parable – a friendly presence that was doomed to scare those it wished to greet. An image of American ambition throughout the world, or at least through American eyes, where we came with the noblest intention of helping and only seemed to scare and enrage the people we helped – so that we had to help them through other means, for instance, by bombing them or overthrowing their governments. We were the world’s Casper the Friendly Ghost.

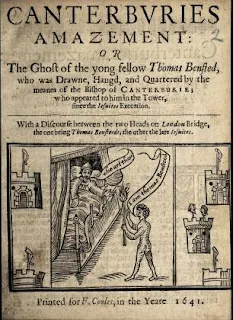

Owen Davies popular history of ghost beliefs, The Haunted, proposes a close relationship between the way corpses were dressed for burial and the appearance of the sheeted ghost. The winding sheet as the last bit of clothing a mortal wears was, in the seventeenth century, supplanted by an increasing use of clothing – and yet still a white robe was often worn. “John Aubrey recounted that the Oxford philologist Henry Jacob, who died on 5 November 1652, appeared a week later to his cousin, the doctor William Jacob, “standing by his Bed, in his Shirt, with a white Capon on his Head”, which was presumably how he was dressed in the coffin.” Here we see an evolutionary fluke: the white sheet takes on a life, or afterlife, of its own with the ghost, as the human corpse is dressed increasingly in other raiment. By the nineteenth century the “bedsheet ghost” image had become standard. Davies thinks that the belief in ghosts, however, liberated itself from the contrivance of the bedsheet due to twentieth century movies. Early comedy silents and talkies extensively used the bedsheet ghost for hilarity. Since ghost belief is usually not about the funnies, but about the unheimlich, ghosts were seen not in sheets, but in their clothes – or sometimes wounded, or bleeding. There was, in the evolution of the ghost costume, this break in “seriousness”, with the children’s bedsheet ghost continuing its iconic run while the real ghost of ghost encounters lost the white sheet entirely.

No comments:

Post a Comment