“I’m so bored. I hate my life.” - Britney Spears

Das Langweilige ist interessant geworden, weil das Interessante angefangen hat langweilig zu werden. – Thomas Mann

"Never for money/always for love" - The Talking Heads

Thursday, July 26, 2012

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

literature's brooder

In the lexicon of cognitive states, brooding has a

distinctly low ranking. We meditate or reflect to achieve illumination;

brooding, however, is the prelude to a tantrum. To think means trying to see

the object of thought whole – but the brooder is peculiarly averse to letting

go of the object of thought, and thus condemns himself to repetition and

compulsion. Argument is meant to persuade us to let the personal go, to, in

effect, accept the autonomy of discourse. In Socrates’ dialogues, the argument

is often treated as though it were some live thing, a spirit, a genius that

must be respected. As such, the argument is extra-personal. From this

perspective, brooding is a failed, or at the very least, a pariah cognitive

act.

Yet, the brooder does have one fierce insight on his side,

for the ideology of cognition obscures the moment of surrender, or sacrifice,

in the release of the object of thought to the drift of discourse – to “what

everybody knows”. The brooder understands that argument’s aspiration to universality

is founded on blooding the personal, and that universality operates under the

rule of polemos, or war. To surrender a thought is, among other things, to

surrender.

Cioran is one of the great brooders. His longer essays can

seem wearying because his sentences are so highly worked that they seem not to

be building an argument, but to be resisting one. The readerly flow of the

essay is impeded by the brilliances of its individual moments. Cioran sometimes

seems like one of those brilliant

conversationalists who never, actually, converse – in as much as conversation

is marked by listening, while the brilliance of the conversationalist seems

impervious to hearing. It bears the mark of a certain deafness. And so it is,

sometimes, with Cioran, especially in his first texts.

Cioran’s development of a reader is a long, painful

abdication of the harangue and the monologue. To hear the other means, in a

sense, letting your style – the verbal front Cioran is so careful to maintain –

allow itself a certain vulnerability. Cioran begins to be readable, for just

this reason, in The Temptation to Exist. It is here that he actually goes the

distance, rather than contenting himself with the pure jab of the phrase.

It is here, too, that he takes as one of his objects of

thought brooding itself – although he doesn’t label the negative space he

opposes to reflection “brooding” as such. What he does is turn upon reflection,

in its institutional forms (literature and philosophy) his suspicion that

underneath the mask of liberality lurks the spirit of resentment, the eternal

return of a grievance. This notion has a long history, and we know its avatars:

Schopenhauer and Nietzsche in particular. It is the reactionary road to

enlightenment.

In Letter on some roadblocks (Lettre sur quelques impasses),

Cioran uses a trick that he employs, as well, in later texts to detach himself

from the brooder’s solipsism: the essay as a message to some correspondent. To

write a letter is not the same as engaging in a conversation, because letters are not subject to the vital

element in conversation – interruption. While conversations go by “turns”, the

violent can bear them away simply by interrupting, and there is nothing in the

rules that forbids this. But letters are, briefly, a space the producer

controls. At the same time, the letter must, however grudgingly, acknowledge

the addressee.

The impasses or roadblocks here collect around the hated

figure of the writer. On the pretence that Cioran is warning his friend against

publishing a book, he launches into an invective against the mere writer – the

littérateur – which, of course, produces a performative “impass” - since Cioran is very much a writer. This

allots him a paradoxical place in his argument. Cioran accepts the cynicism of

the paradox – he even exploits it. It is as though he were not so much a writer

as an anthropologist carrying out fieldwork on people like Cioran – other

writers. And in this guise, he is reporting on their rituals.

What is it that Cioran hates about the writer? It is, I think, the writer’s

tendency to be a moral entrepreneur – to wave about his sensitivity to right

and wrong as though it were a superiority, a talent. Underneath the moral

entrepreneur, Cioran spots the vacuity of the rhetorician:

‘Voltaire was the first litterateur to erect his

incompetence into a procedure, a method. Before him the writer, happy enough to

be next to events, was more modest: doing his job in a limited sector, he

followed his path and stuck to it. No journalist, he was most interested in the

anecdotal aspect of certain solitudes:

his indiscretion was inefficacious.

With our know it all (hableur) things changed. None of the

subjects which intrigued his times escaped his sarcasm, his demi-science, his

need for noise, his universal vulgarity.Everything was impure with him, except

his style…”

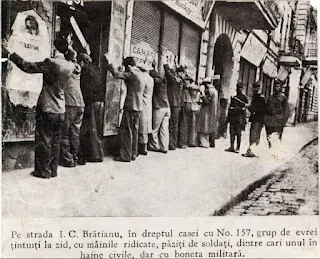

Note a key term for Cioran: impurity. Impurity, for Cioran,

is a hallmark of liberal enlightenment. To understand this, one has to

understand Cioran’s dallying with fascism of the most violent sort in the 30s,

and his brief stance as an admirer of Hitler.

This, actually, is the center of what Cioran brooded upon his whole life

long – his error, here, and his retraction. In the 30s, Cioran was very

explicit about his hatred of the Jews, his desire for war, his faith in great

and therapeutic violence that would stamp some hierarchy on the people for one

thousand years.

Later, in the late thirties in France, he began to change

his mind. He did not, as far as I am aware of, collaborate in the forties.

Rather, he went over and over the logic of his position, starting from the idea

that liberal Europe had suffocated itself under its own dead skin, exiled from

the sources of life itself. And yet, he retreated to the liberal side and renounced

violence: he renounced life-affirming war, and opted for death-affirming peace.

Violence, in Cioran’s view, makes us gigantic, larger than life, and we

renounce it at our peril. In History and Utopia he wrote:

“We employ our clearest vigils in taking apart our enemies

limb from limb, pulling out their eyes and guts, popping and emptying their

veins, crushing and pounding underfoot

each of their organs, and leaving them, for charity’s sake, merely the

enjoyment of their skeletons.” But, clearly, these are visions that Cioran now

does not want to see realized on the streets of the cities (where, as he

remarked somewhere else, he is always mildly astonished that everyone is not

killing everyone else). However, that renunciation has a price. The price is paid

in purity: “Not to venge oneself is to be enchained in the idea of forgiveness,

it is to sink into it, get stuck in it, it is to render oneself impure by the

hatred one strangles in oneself.”

Thus, the hidden dialectic between, on the one hand, the

universal vulgarisers of liberal society, and, on the other hand, the stocking

up of resentment and weakness. What distinguished the Fascist principle for

Cioran was its recognition of the logic of purity: it advocated violence not

for the sake of peace, but because violence was beautiful; bombing was

beautiful because it smashed and hurt our enemies down to the last generation;

mass murder was beautiful because you could see your true self in the pooled

blood of the victims. Cioran, at last, recognized this to be madness, but he

did not renounce the logic of purity – rather, he sought a catharsis through

rehearsing extreme statements in the paradoxical mode. After getting off to a

false start in life, he made false starts a hallmark of his style. And so

brooding, in his work, takes the place of reflection, and reflects, pallidly,

the dangerous fires that he had longed to light himself – and that then ran so

out of control that he was condemned to live in a world that was singed by the

destruction they wrought.

Thursday, July 19, 2012

on definition

Law and mathematics both developed under the steely eye of

the definition. History and literature developed behind definition’s back,

which is why both have a ludicrous bent. To understand the power and essence of

definition, one must free oneself from its seeming inevitability – one must

slip out from literature and history, rather than approach it from law and

mathematics.

Of course, once upon a time, definition was not such a

power. The idea that norms or numbers form a system, and that the system is coherent

and consistent, and that coherence and consistency are systematic – these

ideas, granted, were in the air, but they weren’t taken for granted. This is

not to tell the familiar story of the dreamtime of the folk – it is, rather,

that what a definition is, and why it should have such power, had not yet been

systematically developed. Which is to say that the system as a concept had,

itself, not been systematically developed. There was the moon, stars, tides and

the sun – that is, there was the cosmos – and there were the demons, heroes,

gods, and spirits – there was theology – and, retrospectively, we can see these

as systems. But – to put it in Hegelspeech – the system hadn’t thought of

itself yet.

Once upon a time is the pre-historical category of historical

time, and might be defined by… its lack of definition. Once upon a time does,

however, emerge in history. Although it has the curious property of only being

recognized retroactively – it is like the landscape that is revealed through

the backwindow of a moving car, which, however much we know that it is equal to

the landscape revealed through the frontwindow of the car just a moment ago,

bears the total impression of being behind us – a gestalt-switched twin.

To take a random instance, take IP rights. IP rights bet

everything on definition. But this, up until very recently, wasn’t so.

Take this from Sherman and Bentley’s

The Making of Modern Intellectual Property Law: the British Experience,

1760-1911:

“One of the most important points of contrast

between modern and pre-modern law is in terms of the way the law is organised.

While today the shape of the law is almost universally taken as a given ± the

general category of intellectual property law being divided into subsidiary

categories of patents, designs, trade marks, copyright and related rights ±

under pre-modern law there was no clear consensus as to how the law ought to be

arranged: no one way of thinking had yet come to dominate as the mode of

organisation. Rather, there was a range of competing and, to our modern eyes,

alien forms of organisation. It is also clear that, at least up until the

1850s, there was no law of copyright, patents, designs or trade marks, and

certainly no intellectual property law. At best there was agreement that the

law recognised and granted property rights in mental labour, although the

nature of this legal category itself was uncertain.”

Mental

labor, Sherman and Bentley claim, were treated in modern law the way the old

behavioralists treated ideas and mental events: as irritants and illusions,

having nothing to do with the case. Clearing your mind of mental labor, you go

forward from once upon a time and into the clear light of definitions that are

appropriate for corporate enterprises, or the modern laboratory, or the studio,

or private public collaborations, etc. – all the heavy tinsel of business and

policy speak.

I

mention this to underline the fact that though it may seem quaint to want to

actually examine the philosophical validity of definitions, quaintness can give

way to urgency if the police are at your door and you are accused of providing

links to pirates. It is at that moment that the average schmuck gets a full

glimpse of the armed power of the definition.

And

yet – still, I ask you, what is it? A genre? Is a definition like a poem or an

aphorism or a novel? A piece of language thinking of itself, a piece of

floating meta bumping into our everyday routines? Even asking what it is seems

to bring it up (its shadow swelling ominously) behind me. Is it a god, a demon,

or … after all … a human being?

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

metaphysics of paper4: fallen leaves

The waste books (there’s a Russian word for this, the

“fallen leaves’ genre, - Opavshelistika

-- seem to leave behind some anachronistic, animal trail in the modern system

of literature. That system connects the media and the university in a total

environment of writing that conditions the very notion of the “writer”: he’s a

journalist, a pundit, a poet, a novelist. In the twentieth century, the

writer’s most important work is to produce texts that can be taken up by the

cinema, or by television. The writer in the press produces opinions. Literature

informs the conversation in the press and the classroom, and prefers its

readers to be in the classroom or as members of a bookclub. It prefers, above

all, to see literature as a social function – from this point of view, solitude

is unmasked as bourgeois mystification, or as a psychological aberration.

This system has a place for the aliens of literature who

write the Opavshelistika, but it is in the nature of the

system that taking them seriously means metamorphosing them, curing them of the

solitude in which they are bathed. It is the cure that the waste book writers fear, or devise means to avoid. These

aliens take marginality and solitude as the conditions of the vocation of

writing – and insofar as these are the byproducts of failure (a failure to

market, to circulate, and to achieve the regard that comes with good business),

the waste book writers tend to will failure, to desire it as a sacred thing,

valuable in itself. It is by the crack in the golden bowl, the phrase that

doesn’t reach its end – it is by indirection, evocation, and the proper

appreciation of fortuna in the very production of writing that one reverses the

system’s unbearably invasive presence.

It is from the point of view of the will to failure that

Vasilli Rozanov, in Fallen Leaves, issues his condemnation of writing: “In my

opinion, the essence of literature is false: I don’t mean that the litterateurs

or, again, the ‘present times’ are bad, but instead the entire domain of their

action, and that “all the way to the root.” [my translation from the French]

Rozanov takes up a theme that feeds into the literary

guerilla’s rejection of the system, and its paradoxes. It is a theme that is

tonally always on a foray; however, these forays have a certain midnight air.

It is a theme that lends itself to incendiary grafitti. Yet, its producer, in

the morning, wakes up to the fact that he or she is still a writer. The waste

book, the marginal note, the rejection of literature, is also published, also

circulates, also provides us with a domain of study and of reference. Its

communicative content, however true, is falsified by its communicative form,

its necessary alliance with the system it rejects.

Rozanov sees,

clearly enough, that writing is an ethical – or, rather, cosmological

act.

“ ‘–I am buckling down to write, but is everybody going to

read me?”

Why this “I” and why this ‘they’ll read me”? It really means

“I am more intelligent than the others”, “the others are worth less than me.” It is a sin.”

In one of his letters, Van Gogh expresses the thought that

Jesus did not mean for his words to be written down, and would have been horrified

at the tradition of Christian literature. In a sense, the Gospel is founded on

a radical lack of faith – the writing signals that the apocalypse is

indefinitely deferred. The charismatic moment is lost as soon as it is finds a

medium – this is its melancholy, this is the contradiction that charisma

sublimates. Rozanov was of course

attracted to the apocalyptic moment, and he toyed with the vatic function of

the writer, all the way to the point of marrying his first wife, Appollinaria

Suslova, apparently on the strength of the fact that she had been involved in

that sado-masochistic relationship with Dostoevsky that the latter transposed

to the Gambler. His own vatic denunciations – of Jews, of Communists, finally

of Christ – are violent and, at the same time, never definite, never part of a

set code.

Interestingly, Rozanov was well aware that it was the, as it

were, material conditions of the written that defined the cultural system of

writing that he detested:

“What is new [ Rozanov is writing about his text, Solitaria]

is the tone, once again that of pre-Gutenberg manuscripts. In the Middle Ages,

one didn’t write for the public because, reasonably enough, the printing press

didn’t exist. And the literature of the middle ages are under many aspects

beautiful, strong, touching and deeply beneficent in its discretion. The new

literature has been up to a certain point victim of its excessive manifestation: after the invention of the

printing press, no one in general was capable of that, and no one, moreover,

had the courage to defeat Gutenberg.”

Rozanov himself, according to George Nivat, issued his books

in limited numbers, and he tried very much, in the Fallen leaves, to press the

occasion against the written – where it was written, what needed to be erased,

etc. At the same time, he wrote for the press – he wrote enormously for the

press. And from this perspective it is not so much Gutenberg but the great

yoking together of the press and the steam engine that his writing set out to

defeat, a cosmological struggle against the monologing super-ego.

“My real isolation, almost mysterious, made me capable of

doing it [defeating Gutenberg]. Strakhov said to me “Have the reader always

present in your mind, and write in such a way that everything be clear for

him.” But however much I try to imagine him, I never succeed. I could never

represent to myself the face of a reader, the approbation of a brain, and I

always wrote alone, essentially for myself. Even when I wrote to please, it was

as if I was throwing something over a precipice, making “a great laugh flash

out of the depths”, when there was nobody around me. I always liked to write my

“editorials” in the waiting room of journals, in the midst of visitors, their

discussions with the writers, in the coming and going, the noise, and me

planted there hatching an article “a propos of the last speech in the Duma”. Or

even in the hall of the editorial

board. One time I had to say to my collaborators, sirs, a little quiet

please, I’m writing a reactionary article (gestures, laughs, commentaries). The

hilarity was at its peak. Understanding nothing, just as before.”

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

Arles - travelogue - don't bet your life on posterity

He

didn’t know that it was a Santa Fe sky, say the sky of June 3, 1993,

same lowslung clouds, same flat earth, same encircling hills, same high

blue sky above the clouds, that he was seeing in that summer of 1888,

when he was bothered by the mistral and the rent and the need to

suppress his sexual instincts – the year he lived on half cooked

chickpeas and cheap alcohol – because Van Gogh never set eyes on New

Mexico. I however recognized it instantly, hanging there in the distance

outside the bus window as we swept by the acres of sun flowers and made

the turn into Arles from Tarascon, where we’d go off the train.

Arles it turns out was not the tourist mecca A. and I feared it might

be – seems they had all oiled off to the festival in Avignon – and we

settled in for our jaunt nicely after a small blowup at our hotel --

they tried to palm off a room to us that was deficient in the usual room

things – handles on doors, lampshades, and size, with the bathroom

competing with the bedroom in volume, which was not doing a favor to

either party. We achieved a more brilliant room, then we hied it to the

Place de Forum for lunch. I suggested to A, a little shamefacedly, that

we eat at the restaurant that claims to be the restaurant Van Gogh

painted at night (supposedly ornamenting his huge Cargmanole peasant hat

with little candles so he could see his canvas). Replete with poulpe

and nicoise salade, we then commenced a tour of Arles medievale, and the

river. Arles, like Santa Fe, hosts a lotta art in the summer –

everybody’s favorite stalker, Sophie Calle, had just been in town for an

expo – and it made a nice contrast between the old town’s winding,

narrow street, which crooked along like a map of the blind leading the

blind, and the affiches for past or present attractions which were glued

up all over the pressing walls. The weather was perfect Provence, the

kind that brings in flocks of retired British couples. They’d sneak up

behind us as we would read the carte outside of restaurants: Mum, ‘ere

it says they serve hommelette and frites! I wanted to try the taureau –

Arles is right proud of the running of its bulls, and has run them

through its cuisine as well, with local sauces and cuts. I liked it,

but, such is my feebleness and American decadence, I liked A.’s

entrecote de boeuf even more. The next day we used the ticket we’d

bought to gain entrance to all the sights on the ancien stuff – starting

with Allychamps, Champs Elysees, the street of sarcophagi, then on to

the Arene and the Thermes. A. said Arles was practically Italian. Bought

a book at Actes Sud, the bookstore/publisher, which has set up a

general emporium of culture (coffeehouse, exhibition place, cinema).

Then we lounged fashionably in a few squares, consuming beer, Perrier,

some green syrupy thing, a mystery novel, emails, and time – until we

had to move it to the railroad station and take the express train back

to Montpellier. We were sunburned, well fed, and pretty happy about our

one day jaunt/anniversary celebration.

Van Gogh, of course, left

Arles under less happy circumstances. After the unfortunate ear act and

the shutting up in the hospital, fifty Arles citizens signed a petition

to the mayor to have him expelled, which depressed him a lot. Reading

his letters, it is easy to see what an impossible man he was, messianic

in that D.H. Lawrence manner – but I have a huge weakness for the

wrestlers with the chthonic soul, the underground men, those who fizz

like some malfactured cherry bomb, refusing either to explode or sputter

out, and thus dangerous to approach. If only, for his sake, he had sold

a few paintings in his lifetime! If only, for our sake, he had sold a

few less paintings, or at least for less money, in his afterlife! Those

guys at the fin de siecle counted a lot on the Nachwelt – on the future.

They staked their work on posthumous fame. But, as Karl Kraus once

wrote, do we, the living, really deserve to be a posterity? Kraus

doubted we were up to the task. I do too.

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

metaphysics of paper 3

Viele Werke der Alten sind Fragmente geworden. Viele Werke

der Neuern sind es gleich bei der Entstehung. - Schlegel

There’s a story in Strabo that runs like this: “Neleus

succeeded to the possession of the library of Theophrastus, which included that

of Aristotle; for Aristotle gave his library, and left his school, [379] to

Theophrastus. Aristotle was the first person with whom we are acquainted who

made a collection of books, and suggested to the kings of Egypt the formation

of a library. Theophrastus left his library to Neleus, who carried it to

Scepsis, and bequeathed it to some ignorant persons who kept the books locked

up, lying in disorder. When the Scepsians understood that the Attalic kings, on

whom the city was dependent, were in eager search for books, with which they

intended to furnish the library at Pergamus, they hid theirs in an excavation

under-ground; at length, but not before they had been injured by damp and

worms, the descendants of Neleus sold the books of Aristotle and Theophrastus for

a large sum of money to Apellicon of Teos. Apellicon was rather a lover of

books than a philosopher; when therefore he attempted to restore the parts

which had been eaten and corroded by worms, he made alterations in the original

text and introduced them into new copies; he moreover supplied the defective

parts unskilfully, and published the books full of errors. It was the

misfortune of the ancient Peripatetics, those after Theophrastus, that being

wholly unprovided with the books of Aristotle, with the exception of a few

only, and those chiefly of the exoteric kind, they were unable to philosophize

according [380] to the principles of the system, and merely occupied themselves

in elaborate discussions on common places. Their successors however, from the time

that these books were published, philosophized, and propounded the doctrine of

Aristotle more successfully than their predecessors, but were under the

necessity of advancing a great deal as probable only, on account of the

multitude of errors contained in the copies.”

When matter emerges clumsily and definitively in the world of letters, it does so through certain favored modes and occasions: the fragment, the ruin, the lost. These expose the word’s entanglement in matter, the limit to its flights, the impossibility of the heaven of pure sense. The gnostic attitude begins with a deep appreciation of these seemingly accidental events. It is a revelation, one never to be gotten over by the prepared soul, that the text can be lost or patched, the copyist can mistake or the copy be blotted, the letter lost, the word abandoned or interrupted. These events, in the great tradition, the mainstream, are waved away as contingencies, but the gnostic draws a different metaphysical conclusion, which is that these events are inherent to the pact between sound and sense, paper and text, and that the entanglement between matter and letter, or the code and the message, ruins all the tower of Babel schemes for the one true metalanguage. This metaphysical conclusion, in modernity, strengthens the margins against the center, or the mainstream. The gnostic attitude flows into Marx’s dialectical materialism, which exploits the power of the negation of the negation, and into like enterprises that bet on the return of the repressed. It connects Marx with Michelet’s witch, who, in the dark night of the feudal claim to have represented the totality of the order of creation in the social order, registers her protest by reciting the Lord’s Prayer backwards, in following the “grand principe satanique que tout doit se faire à rebours, exactement à l’envers de ce que fait le monde sacré” – “great satanic principle that everthing must be done backwards, exactly the reverse of what the sacred world does.” More commonly, the gnostic appears, in modernity, in the guise of the clerk, bureaucrat, functionary who becomes aware, to a greater or lesser degree, of his non-productive function in the sphere of circulation. He becomes a metaphysical whistle-blower – a Kafka, a Pessoa, a Bartleby.

Sunday, July 08, 2012

On the hedgehog

In a

famous essay, the Fox and the Hedgehog, Isaiah Berlin creates a taxonomy of

thinkers based on a line from Archilochus: ‘The

fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.’ The thinkers who

know one thing are, in Berlin’s view, systematic thinkers. All thought tends to

the center, among them, the one big thing that explains the world. The Foxes

are anti-systematic. They are essayists, explorers of the intersections of

thought and experience, from the scope of which they take it no principle can

absorb experience without something stubborn and unabsorbed remaining from that

experience – what Thomas Nagel calls the quality of “what it is to be like”…

Now evidently,

Berlin is using the hedgehog image as a way into talking about the mindset of

certain writers, and in particular, of Tolstoy. Tolstoy has to an extreme

degree the fox’s virtue, which is to understand the difference made by

experience, by what it is to be like – and he has to an extreme degree the

hedgehog’s vice, which is a thirst for the god’s eye view that will not rest

until everything has been settled according to some central principle.

However, what gets a

little lost here is why Archilochus chose the hedgehog, of all creatures, to

represent the systematic viewpoint – if Berlin’s interpretation is right.

There is, perhaps,

another way of looking at the hedgehog’s emblematic meaning. In Schlegel’s

Fragments – which is, among other thing, a defense of the Fragment as a genre

of philosophical knowledge - the

hedgehog, Igel in German, reappears – perhaps in some reference to

Archilochus’s line:

“A fragment must be

like a tiny artwork, wholly sundered from the surrounding world and complete in

itself like a hedgehog.”

What Schlegel’s

image proposes is not that the one great thing the hedgehog knows absorbs the

world – rather, it separates a tiny, particular experience from the world and

completes it. The paradoxical stress, here, is between the fragment and perfect

or complete closure [in sich selbst vollendet sein]. While Berlin’s does not

begin his essay by asking about what it is, in the hedgehog, that leads to the

“one big thing’ he knows, Schlegel – whether consciously referencing

Archilochus or not – returns to the ethological, or perhaps I should say ethnological, base of the comparison. [After

I wrote this, I discovered that Anthony

Grafton had been here before me – noticing this echo, too, in an essay on

fragments in the classical tradition]

Stephen Gould,

writing about Archilochus’s image, quotes Erasmus’s latin translation, which

preserved the image in the humanist curicculum: multa novit vulpes, verum echinus unum magnum. Gould also,

rightly, goes to Pliny for some sense of what the hedgehog meant to the

ancients. However, Pliny deserves to be quoted at length, for it is in Pliny

that we get a sense of the hedgehog figuring in a certain kind of game or work

– that of hunting. This aspect is neglected in Gould’s essay.

“When

they perceive one hunting of them, they draw their mouths & feet close

togither, with all their belly part, where the skin hath a thin down: & no

pricks at all to do harme, and so roll themselves as round as a foot-ball, that

neither dog nor man can come by any thing but their sharpe-pointed prickles. So

soon as they see themselves past all hope to escape, they let their water go

and pisse upon themselves. Now this urine of theirs hath a poisonous qualitie

to rot their skin and prickles, for which they know well enough that they be

chased and taken. And therefore it is a secret and a special pollicie, not to

hunt them before they have let their urine go; and then their skin is verie

good, for which chiefly they are hunted: otherwise it is naught ever after and

so rotten, that it will not hang togither, but fall in peeces: all the pricks

shed off, as being putrified, yea although they should escape away from the

dogs and live still: and this is the cause that they never bepisse and drench

themselves with this pestilent excrement, but in extremitie and utter despaire:

for they cannot abide themselves their own urine, of so venimous a qualitie it

is, and so hurtfull to their owne bodie; and doe what they can to spare

themselves, attending the utmost time of extremitie, insomuch as they are ready

to be taken before they do it.”

This

habit of the hedgehog – or at least this trait attributed to the hedgehog –

puts us closer to the particular knowledge possessed by the hedgehog, in

Archilochus’s verse. It is knowledge in a field – the field of hunting – and

the hedgehog, far from being the systematic master, is the victim, the object

of the chase. The domain of hunting seems to be behind the

fables that Archilochus uses as his references – fables now obscure to us,

although we still know the stock of them labeled with the name of their

supposed author, Aesop.

One of the reasons

Berlin poses the question of Tolstoy’s philosophy of history and how seriously

we are to take it is that he is concerned, as one of the premier Cold War

intellectuals, with Marx’s philosophy of history. What he wants to know is whether

it is possible to get the hedgehog’s view of history outside of the reification

of history – that is, outside of an explanation of causes (attributed to

“history’’) that is merely an affirmation of effects. The nineteenth century in

which he places Tolstoy was hypnotized by the verb, ‘determine’. That x

‘determines’ y seemed to say something more profound about y’s connection to x

than to say x causes y. Determine – in German, Bestimmung – announces a power

relationship that quickly slides into myth – the myth of the relation between

creator, who shapes, and the creature, who lives within the creator’s lines,

the creator’s survey plat.

“History alone – the

sum of empirically discoverable data – held the key to the mystery of why

what happened

happened as it did and not otherwise; and only history, consequently, could

throw light on the fundamental ethical problems which obsessed him as they did

every Russian thinker in the nineteenth century.What is to be done? How should

one live? Why are we here?What must we be and do? The study of historical

connections and the demand for empirical answers to these proklyatye voprosy1 became fused into

one in Tolstoy’s mind, as his early diaries and letters show very vividly.”

Berlin is moving his

pieces forward in the essay in broad, easy gestures, which has the advantage of

making his essay accessible and interesting, and the disadvantage that comes

from refusing to nitpick: that is, gliding over certain philosophically

important issues. In particular, the junction of empirical and positivist does

a lot of work for Berlin in the essay, even as one has to question its

self-evidence. Positivism was not simply about the empirical – it was about

progress. It was about a pattern in history that is above the empirical, the scatter

of facts. Similarly, the romantic

protest against the great

anti-metaphysical writers of the eighteenth century was not, as Berlin actually

knew, simply a rejection of science. Schlegel was not rejecting science so much

as questioning its universal application – the fragment, in Schlegel’s view,

presents a sort of monadic block to the statistical method of science. It

doesn’t transcend the empirical – far from it. It dwells in the empirical, it

weighs down experience with all its force, it presents its ‘bristles’ to the

world like a hedgehog. And it does so in the consciousness that it is being

hunted. For science, here, is no neutral social mechanism – it is used with

definite aims.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Love and the electric chair

It is an interesting exercise to apply the method of the theorists to themselves. For instance, Walter Benjamin, who was critiqued by Ador...

-

You can skip this boring part ... LI has not been able to keep up with Chabert in her multi-entry assault on Derrida. As in a proper duel, t...

-

Ladies and Gentlemen... the moment you have all been waiting for! An adventure beyond your wildest dreams! An adrenaline rush from start to...

-

LI feels like a little note on politics is called for. The comments thread following the dialectics of diddling post made me realize that, ...