We have tried to show that the dismissal of Adario as a figment of Lahontan’s imagination, or as the noble savage which romantically stands in the way of the modern admiration of itself – that moment of vulgarity, of the ultimately base, the truly modern – is an intellectually shaky stance. In its movement, it does conceal a truth that it doesn’t recognize – that there is no reason to suppose that all cultures match, as it were, the cultures of Europe. Match as agreeing with, or antithetical too. The possibility that two cultures can miss each other entirely is the possibility of counter-generality, unlimited. Although we like to think that the Gods play on a game board extensive enough that every pawn can find a footing. The myth of the myth of the noble savage is based, as we have said, on the myth of the civilized European, the features of which (belief in science, for instance) took in a very, very small minority of Europeans. On the other hand, as Bruce Trigger has said, the Europeans had developed an adaptability to circumstances that ultimately made them powerful not only outside, with their guns and metallurgy, but inside, with their need to be in the subject, to have the subject believe. It is this level where the savage and the civilized take their real places, masks off. But it is a level in which, to the incredulity of the governors, the slip and slide between one role and the other becomes incredibly easy. Kurz goes native, the native goes Kurz. Nous sommes tous des sauvages.

Adario takes on the system that he knows is killing him at its most vital point: the mine and the thine. This sorting procedure stalks through the pox. It also stalks through the Europe of savages, the interior, the Leibeigne of Hesse, the church governed principalities, the urban mechanics, the accursed estates.

Adario’s attack takes an interesting tack when we come to that issue which must be dear to libertine ethnologues: nudity. If Paradise was the déjà vu of the explorers, Eden just ahead of them, at the center of Paradise was the central and first act of the opened eye: clothing oneself. God’s first animal to cover itself in shame as to what it showed. The Europeans always found the ways in which the natives covered themselves to be disquieting. In the case of the Hurons and Iroquois, what disturbed was not the allure of tits and cunt, the supplement to our voyage of Cytheria, down the trembling female body – no, it was dick. Turnabout that has been muted, even now, among those who would nose out our Orientalist ancestors, and one of the reasons that Lahontan’s biographer finds him slightly obscene. Just as Adario found the European propensity for daring décolleté slightly obscene.

About which, more in the next post.

“I’m so bored. I hate my life.” - Britney Spears

Das Langweilige ist interessant geworden, weil das Interessante angefangen hat langweilig zu werden. – Thomas Mann

"Never for money/always for love" - The Talking Heads

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Lahontan

“Just look at P…, he continued, when she plays Daphne, and, chased by Apollo, turns to look at him – her soul sits in the turmoil of the small of her back; she bends, as though she wanted to break, as a naiad out of the school of Bernini. Look at the young F., then, when he, as Paris, stands among the three Goddesses and hands the apple to Venus. His entire soul sits (it is a shock to see it) in his elbow.

Such mistakes, he added, disconnectedly, are unavoidable, since we ate from the Tree of Knowledge. Paradise is still locked up and the Cherub is behind us; we must make a trip around the world, and see whether perhaps it isn’t still open somewhere in the back.” – Kleist, On the Marionette Theater.

I have danced in these threads so far without, astonishingly enough, mentioning Paradise. But now is the time. Daphne crouches, Paris extends the apple. Once upon a time, when Eve was not coy, the animals could talk, and an island floated up to the people, trailing a cloud above it, on which the Gods were standing. Paradise, of course, it was always a question of Paradise in the Encounter.

… So what was he thinking, sitting there in 1707. There – in Amsterdam? In Copenhagen? As he took up the quill, was he thinking that he had never ceased traveling? That it was all as if he had never gotten out of that infinite forest, that it was still ceaselessly snowing, as he had first seen it from the deck of a boat, leaving debts he could hardly understand behind him, status, college, a dead father tracked down and staked through the heart by the immovability of a society that knew nothing of progress but everything about prestige. The ancients feuded with the moderns on the torrents of the Pau. Lom d’arc, Baron of Lahontan, his father, cleared the Adour River up to Bayonne. He’d never seen a river like the St. Lawrence. Rivers ran fatally through his life.

Did he think that the blizzard of snow and the forest were mirror images one of the other, both wildernesses through which only the most artful entity, the Manitou, could dodge?

The tricks you learn. Looking at his hand, the souvenir of the stump where his little finger used to be. Left for the filthy bottomdwellers at some Wisconsin portage…

According to his biographer and self appointed judge, Joseph-Edmund Roy, the Baron de Lahontan’s father had exhausted his own resources and a great part of his life in the work of clearing the river. In the end, he succeeded, making Bayonne a commercial port. His reward was to be sued for debt, and to fail, in turn, to collect the debts owed him.

Lahontan. Lahontan was a small village which, at one time, was comprised in the territory held by Montaigne's family. Montaigne mentions it as a funny, primitive place. Peculiarly cut off. The story is that the village kept its own customs, generation after generation, until an outsider married into the place, and introduced all the modern troubles: lawsuits, doctors, exchange.

In the shadow of the Pyrenees. He was eight years old when his father died. The son of the second wife.

Baron de Lahontan was seventeen when he first saw New France. Ten years later, he turned his back on it for the last time, a convoluted quarrel such as he always seemed to be getting into. Deserting his post to take sail on a ship that he bribed to drop him off on the Portugese shore. By then, he was suffering from a bit of persecution complex about returning to France. Afraid of being seized for debt, or insubordination. He’d made enemies, god knows. The Sieur de Pontchartrain paid men to silence the like of small fry nobility.

“On the 23 Jume 1699, the parliament in Paris issued an arrest – a warrant – in this affair. It is enough to say that the text of the warrant mentons more than 150 summonses, requests, replies, sustainments, contradictions, arres and sentences, without counting the production of supplementary motions. We find more than sixty parties intervening. They come from Paris, Tours, Rouen and every corner of Bearn. The procedures, which began in 1664, were continued annually up to 1699 when the warrant on the distribution of money was issued, but in 1789, the city of Bayonne was still fighting with the creditors of the Lahontan family.”

Perhaps it is a winter morning. The day is cloudy. He sets his pen to the foolscape. The expriest will visit him later in the day, and they will go over the dialogue. Ex-priest, but still a priest – not the kind of creature he likes. Something about them leaves him breathless with hostility. And the ex-priest was common, there was no denying it. Some peddler’s boy, he imagined. He remembers getting out of a tough spot in Spain, no money for the inn, using the gestures he’d observed used by the Jesuits among the Huron, and the gestures, too, that the local healer used, setting himself up as a montebank, paying the bill, getting a coach. The baron-medecin. Out of Moliere and Don Quixotte. Now, he receives, under a cover name, money from a family friend, which he invests in bills of exchange, creaming off a certain percentage for himself.

He’ll last be seen hunting. In a forest on an estate in Luxemberg. Leibniz mentions him. Leibniz the pious man, Lahontan the libertine sceptic. What is broken in the network, what we don’t see. Only blind guesses.

The snow comes down day after day. He learns an Algonquin tongue. Reads Petronious. Lascivious scenes before going to sleep. A priest, one day, comes into his room, spots the book, seizes it and tears it into shreds. He will always resent this insult.

Did he dine with Bayle? When Adorio arose before him, the Huron philosophe. Who had visions of the undoing of his people in every baptism and ever poxy corpse. Or who was the pious Indian leader who died in Montreal and was given a Christian funeral. What do you know about people?

Lahontan had once wanted to discover something. The Long River. A foolish ambition to garner the kind of prestige that LaSalle, that madman, had gained. His party sailing past a burned out post he never noticed, a post that had been set up by Lasalle in Missouri, where a trunk was emblazoned with the words that would continue eternally return to whisper in select ears in the Artificial Paradise: Nous sommes tous des sauvages.

The Black Robes, impressing the Hurons with the announcement that the world turned around the sun. Meanwhile, back in Lahontan, a man who professed to believe that the world turned around the sun, if anyone had been so foolishly inclined to contradict the evidence of his senses, would have been visited by the priests and the local authorities and would, assuredly, recant. Civilization – not a word in general use. Citizen. Not a word in general use. Subject – ah, subjects. To turn the savages into subjects of the king. That was the project. A word undergoing some strange rhetorical stress, subject.

The ex priest, they say, added details only a cleric would know. Citations from Origen – would the 30 year old Lahontan have read Origen? And of course distance buries everything, even the Huron chief who is disallowed, as time goes by, his own critique of European civilization. No, they would speak in childish metaphors. No religion, these people. Cruel torturers. Will do anything their women tell them to do.

8 Nov. 1710

I hope you will pardon the liberty I take in imposing on your goodness for a subject about which I am going to speak to you.

My friend Bierling asked me, by a letter expressly for that purpose, if the Baron de Lahontan with his voyage and his dialogues is something imaginary and invented ... or if this is a real man who has been in America and who has spoken to a real savage named Adario. For one judges that an entire people living tranquilly among themselves without magistrates, without trials, without quarrels, is something as incredible as those hermaphrodite Australians. The discourse of Adoria has confirmed these people in their Pyrrhonism.

You will ask me, Mademoiselle, what relevance does this have for me, and shouldn’t I address M. de Lahontan himself. I will tell you why. One wants to know if Lahontan is a real and substantial man. As he was dangerously ill this summer, he could be dead (God forbid), the gout may have risen and killed him since, or he could have been saved through the application of the horns of some dear more savage than the savage animals which are respected in America.

One may perhaps judge that I have a secret reason and that the first serves only as a pretext. But say what you will, only be content with the subject of my letter. If monsieur le Baron of Lahontan is well, as I don’t doubt, he won’t be angry to have become a problem like Homer or more like Orpheus…”

- G.W.F. Leibniz

And so he sits there – where? – scratching on foolscape, the perpetual refugee. As new as the subject, as new as the citizen. Whose home moved out from under him. An island appeared, it trailed clouds, the gods disembarked, and they distributed holy objects.

Such mistakes, he added, disconnectedly, are unavoidable, since we ate from the Tree of Knowledge. Paradise is still locked up and the Cherub is behind us; we must make a trip around the world, and see whether perhaps it isn’t still open somewhere in the back.” – Kleist, On the Marionette Theater.

I have danced in these threads so far without, astonishingly enough, mentioning Paradise. But now is the time. Daphne crouches, Paris extends the apple. Once upon a time, when Eve was not coy, the animals could talk, and an island floated up to the people, trailing a cloud above it, on which the Gods were standing. Paradise, of course, it was always a question of Paradise in the Encounter.

… So what was he thinking, sitting there in 1707. There – in Amsterdam? In Copenhagen? As he took up the quill, was he thinking that he had never ceased traveling? That it was all as if he had never gotten out of that infinite forest, that it was still ceaselessly snowing, as he had first seen it from the deck of a boat, leaving debts he could hardly understand behind him, status, college, a dead father tracked down and staked through the heart by the immovability of a society that knew nothing of progress but everything about prestige. The ancients feuded with the moderns on the torrents of the Pau. Lom d’arc, Baron of Lahontan, his father, cleared the Adour River up to Bayonne. He’d never seen a river like the St. Lawrence. Rivers ran fatally through his life.

Did he think that the blizzard of snow and the forest were mirror images one of the other, both wildernesses through which only the most artful entity, the Manitou, could dodge?

The tricks you learn. Looking at his hand, the souvenir of the stump where his little finger used to be. Left for the filthy bottomdwellers at some Wisconsin portage…

According to his biographer and self appointed judge, Joseph-Edmund Roy, the Baron de Lahontan’s father had exhausted his own resources and a great part of his life in the work of clearing the river. In the end, he succeeded, making Bayonne a commercial port. His reward was to be sued for debt, and to fail, in turn, to collect the debts owed him.

Lahontan. Lahontan was a small village which, at one time, was comprised in the territory held by Montaigne's family. Montaigne mentions it as a funny, primitive place. Peculiarly cut off. The story is that the village kept its own customs, generation after generation, until an outsider married into the place, and introduced all the modern troubles: lawsuits, doctors, exchange.

In the shadow of the Pyrenees. He was eight years old when his father died. The son of the second wife.

Baron de Lahontan was seventeen when he first saw New France. Ten years later, he turned his back on it for the last time, a convoluted quarrel such as he always seemed to be getting into. Deserting his post to take sail on a ship that he bribed to drop him off on the Portugese shore. By then, he was suffering from a bit of persecution complex about returning to France. Afraid of being seized for debt, or insubordination. He’d made enemies, god knows. The Sieur de Pontchartrain paid men to silence the like of small fry nobility.

“On the 23 Jume 1699, the parliament in Paris issued an arrest – a warrant – in this affair. It is enough to say that the text of the warrant mentons more than 150 summonses, requests, replies, sustainments, contradictions, arres and sentences, without counting the production of supplementary motions. We find more than sixty parties intervening. They come from Paris, Tours, Rouen and every corner of Bearn. The procedures, which began in 1664, were continued annually up to 1699 when the warrant on the distribution of money was issued, but in 1789, the city of Bayonne was still fighting with the creditors of the Lahontan family.”

Perhaps it is a winter morning. The day is cloudy. He sets his pen to the foolscape. The expriest will visit him later in the day, and they will go over the dialogue. Ex-priest, but still a priest – not the kind of creature he likes. Something about them leaves him breathless with hostility. And the ex-priest was common, there was no denying it. Some peddler’s boy, he imagined. He remembers getting out of a tough spot in Spain, no money for the inn, using the gestures he’d observed used by the Jesuits among the Huron, and the gestures, too, that the local healer used, setting himself up as a montebank, paying the bill, getting a coach. The baron-medecin. Out of Moliere and Don Quixotte. Now, he receives, under a cover name, money from a family friend, which he invests in bills of exchange, creaming off a certain percentage for himself.

He’ll last be seen hunting. In a forest on an estate in Luxemberg. Leibniz mentions him. Leibniz the pious man, Lahontan the libertine sceptic. What is broken in the network, what we don’t see. Only blind guesses.

The snow comes down day after day. He learns an Algonquin tongue. Reads Petronious. Lascivious scenes before going to sleep. A priest, one day, comes into his room, spots the book, seizes it and tears it into shreds. He will always resent this insult.

Did he dine with Bayle? When Adorio arose before him, the Huron philosophe. Who had visions of the undoing of his people in every baptism and ever poxy corpse. Or who was the pious Indian leader who died in Montreal and was given a Christian funeral. What do you know about people?

Lahontan had once wanted to discover something. The Long River. A foolish ambition to garner the kind of prestige that LaSalle, that madman, had gained. His party sailing past a burned out post he never noticed, a post that had been set up by Lasalle in Missouri, where a trunk was emblazoned with the words that would continue eternally return to whisper in select ears in the Artificial Paradise: Nous sommes tous des sauvages.

The Black Robes, impressing the Hurons with the announcement that the world turned around the sun. Meanwhile, back in Lahontan, a man who professed to believe that the world turned around the sun, if anyone had been so foolishly inclined to contradict the evidence of his senses, would have been visited by the priests and the local authorities and would, assuredly, recant. Civilization – not a word in general use. Citizen. Not a word in general use. Subject – ah, subjects. To turn the savages into subjects of the king. That was the project. A word undergoing some strange rhetorical stress, subject.

The ex priest, they say, added details only a cleric would know. Citations from Origen – would the 30 year old Lahontan have read Origen? And of course distance buries everything, even the Huron chief who is disallowed, as time goes by, his own critique of European civilization. No, they would speak in childish metaphors. No religion, these people. Cruel torturers. Will do anything their women tell them to do.

8 Nov. 1710

I hope you will pardon the liberty I take in imposing on your goodness for a subject about which I am going to speak to you.

My friend Bierling asked me, by a letter expressly for that purpose, if the Baron de Lahontan with his voyage and his dialogues is something imaginary and invented ... or if this is a real man who has been in America and who has spoken to a real savage named Adario. For one judges that an entire people living tranquilly among themselves without magistrates, without trials, without quarrels, is something as incredible as those hermaphrodite Australians. The discourse of Adoria has confirmed these people in their Pyrrhonism.

You will ask me, Mademoiselle, what relevance does this have for me, and shouldn’t I address M. de Lahontan himself. I will tell you why. One wants to know if Lahontan is a real and substantial man. As he was dangerously ill this summer, he could be dead (God forbid), the gout may have risen and killed him since, or he could have been saved through the application of the horns of some dear more savage than the savage animals which are respected in America.

One may perhaps judge that I have a secret reason and that the first serves only as a pretext. But say what you will, only be content with the subject of my letter. If monsieur le Baron of Lahontan is well, as I don’t doubt, he won’t be angry to have become a problem like Homer or more like Orpheus…”

- G.W.F. Leibniz

And so he sits there – where? – scratching on foolscape, the perpetual refugee. As new as the subject, as new as the citizen. Whose home moved out from under him. An island appeared, it trailed clouds, the gods disembarked, and they distributed holy objects.

Sunday, February 15, 2009

More on the myth of the myth of the noble savage

It is hard to cut through the scrim. While the Jesuits were trying to impress the Hurons with the latest discoveries in natural philosophy, in 1677, the police in Paris were arresting Magdelaine de la Grange and charging her, at that moment, with murder and forging a marriage certificate between herself and the lawyer she was living with. This was the beginning, it turned out, of the "Affair of Poisons", in which the highly civilized nobility of Louis XIV's court were found to be frequenters of fortune tellers, back ally witches, and implorers, upon the right occasion, of the devil. The affair was investigated by men who assembled in a room in which all the walls were shrouded with black cloth, and the testimonies were elicited by torture.

It is the latter culture that historians call the civilized one, as opposed to the savages of New France. Why? Historians are like shopkeepers in a Mafia dominated section of Queens – they are overly impressed with guns. Civilization equals a lotta guns. Savages on the one side, the urban society with books and guns on the other. In this divide, it is the soft Westerner who praises the lifestyle of the savages as having any advantage over the civilized. Thus, one puts down the myth that they were ecologically aware. The myth that they were gentle. This or that myth. The iconoclasm, however, never gets out of hand – there is not putting down of the myth that the civilized were civilized. Thus, contact testimony to the stature of the Indians (a very good indicator of well being), or the non-hierarchized religious organization of certain Indian nations, or the political and personal power females in certain Indian nations enjoyed is ignored. To emphasize these things is to see the savages through a “soft” focus. It is to lose track of civilization.

Of course, historians of the Americas often are astonishingly ill informed about the history of the European societies, and view European protagonists as, of course, agents who have experienced the city, the mechanical philosophy, the horse, uh, mathematics and all the rest of it. That the Copernican system would have astonished most of the inhabitants of Paris and certainly most of the inhabitants of Lahontan – a little region near the Pyrenees – is something quite beyond the myth of the noble savage argument.

James P. Ronda, in 1977, published a charming article entitled "We Are Well As We Are": An Indian Critique of Seventeenth-Century Christian Missions”, in which he quotes testimony that was sent back in the Jesuit Relations – a sort of newsletter of the missionaries in New France. When the Jesuits came among the Huron to announce the good news and generally accelerate the civilizing process, The Hurons listened with the utmost politeness – which had something to do with the guns, and something to do with wanting allies in the raids against the Iroquois. This paragraph is so lovely it makes me melt:

“Hurons, both converts and traditionalists, found the doctrines of sin and guilt confusing. "How . .. do we sin?" asked one man. "As for me, I do not recognize any sins."'2 When the missionaries attempted to explain how one could sin even in one's thoughts, they often encountered utter disbelief. "As for me, I do not know what it is to have bad thoughts," replied one old man. "Our usual thoughts are, 'that is where I shall go,' and 'Now that we are going to trade, I sometimes think that they would do me a great favor when I go down to Kebec, by giving me a fine large kettle for a robe that I have.' "13 Even among converts the missionaries met considerable resistance to the ideas of sin and guilt. When a recently converted Huron came to confess, the missionaries rejoiced: "He was about to accuse himself," they thought, "of having violated what the Father had taught." They were soon disappointed, however, for the convert came rather to accuse another Indian of stealing his cap. He had assumed that this "confession" would win him another cap from the Jesuit.”

That one old Huron man neatly sums up a whole line of thought in Beyond Good and Evil.

“Indians tended to view the conceptions of heaven and hell with even less regard. The Huron, Montagnais, and New England native Americans all Indians tended to view the conceptions of heaven and hell with even less regard. The Huron, Montagnais, and New England native Americans all anticipated an afterlife but assumed that it would be spent in morally neutral surroundings, not in a place of heavenly reward or hellish punishment. The Hurons spoke of a "village of souls" populated by the spirits of the dead. Life in those villages was believed to resemble life on earth with its daily round of eating, hunting, farming, and war-making. Missionary efforts to impress Indians with the delights of heaven met with disbelief and derision. Because the Jesuits described heaven in European material terms, the Hurons concluded that heaven was only for the French. When one Huron was asked why she refused to accept the offer of eternal life, she characteristically replied, "I have no acquaintances there, and the French who are there would not care to give me anything to eat.""15 The father of a recently deceased convert child urged the missionaries to dress her in French garments for burial so that she would be recognized as a European and permitted entrance into heaven.'6 Most native Americans rejected the European heaven, desiring to go where their ancestors were. The mission compounded this rejection by telling potential converts that heaven contained neither grain fields nor trading places, neither tobacco nor sexual activity-surely a dreary prospect. Some Indians resented the notion that one had to die in order to enjoy the blessings of conversion, while others observed that an everlasting life without marriage or labor was a highly undesirable fate.'7 Missionaries provoked an even stronger negative response when they preached about everlasting punishment in a fiery hell. The hell the Jesuits described must have profoundly affected their Indian listeners, for the Huron and Montagnais were no strangers to the horrors it was said to contain. The torture by fire of captured warriors was a customary part of Iroquoian warfare, and Huron and Montagnais men knew that such would be their fate if they fell into enemy hands. They themselves practiced torture rituals on their own captives, applying burning brands and glowing coals to the bodies of the condemned before execution. Men and women who had participated in such events must have responded emphatically to the idea of hell. But the evidence suggests that most responded in disbelief. Though the torments of hell were all too imaginable, they were rejected because they seemed to serve no useful purpose. In fact, the most common objection to the Christian hell was that it only lessened the delights of earthly life. "If thou wishest to speak to me of Hell, go out of my Cabin at once," exclaimed one Huron. "Such thoughts disturb my rest, and cause me uneasiness amid my pleasures." Hurons resented what seemed to them a Christian obsession with death and punishment. This resentment may have sprung from Huron anxiety about death and about the uneasy relationship between the living and the spirits of the dead.'8 Whether or not disturbed by this prospect, one Huron spoke for many when he said simply, "I am content to be damned.''19

Other native Americans went beyond rejecting hell as an unpleasant place to question the basic Christian assumptions about postmortem punishment. "We have no such apprehension as you have," said a Huron, "of a good and bad Mansion after this life, provided for the good and bad Souls; for we cannot tell whether every thing that appears faulty to Men, is so in the Eyes of God."20”

Given these responses, it is peculiar that Baron Lahontan’s dialogues with Adario, in actuality a Huron named Kondiaronk, have been almost unanimously judged by historians as gross fictions, attributing words to this Huron that could never have come out of his mouth. After all, the argument runs, many of those words are sharp criticisms of religion in the vein of Bayle himself – and the Indians obviously weren’t capable of such complex concepts. Or so say those who are anxious, very anxious, to use the “myth of the noble savage” to close down the discussion of the Encounter. If you run the myth of the myth of the savage to earth, you will find that it arose in a painfully familiar context in the early twentieth century. One of its most influential designers was a historian and literary critic named Gilbert Chinard. Chinard began writing in France before World War I, and settled in the U.S. after the war. He was prolific. And, from the beginning, he was carrying a torch for an essentially reactionary political philosophy. Chinard’s thesis was that Lahontan created the noble savage myth which was appropriated by Rousseau, and used to spread a diseased notion of egalitarianism of which the dire effects were seen in the Revolution. It is interesting that a thesis which, in 1913, was so obviously attuned to a certain political current in France. Chinard was basically a reactionary modernist, with all the identifying marks: the attack on Rousseau as the precursor of a dangerous romanticism; the nostalgia for a certain image of the ancien regime; the notion of classicism as clarity; the almost hysterical language about the French Revolution. From the Action Francais to T.S. Eliot, these were themes of the radical conservative program. Translated to the U.S., these themes really became pertinent after World War II, in the Cold War reaction to the 30s leftist culture. Partly the success of the myth of the savage was due to Chinard himself, who loomed largely in the study of colonial and revolutionary Americo-Franco relations between the wars. He published both in French and English, and was a brilliant scholar of the colonial/Revolutionary period, one of the few scholars with a grasp of the full trans-Atlantic scene in which the intellectual history of the Enlightenment unfolded. In this history, certain testimonies were given weight, and certain were tossed out. Lahontan, whose works – to give Chinard his due – were edited and republished by Chinard, was dismissed without, evidently, first hand reading. For instance, this is George R. Healy in an article from 1958 entitled, The French Jesuits and the Idea of the Noble Savage, in which one is astonished to read this: “The men most influential in popularizing the notion of savagery as a condition superior to contemporary civilization – Lahontan and Rousseau, for example – were surely more given to the manufacture of titillative paradox than to research among the hard sociological facts.” As if George R. Healy had ever met a 17th century Huron or spoken his language, or drank chocolate in an eighteenth century Parisian salon. If anybody had a comparative sense of ‘civilization’ vs. ‘savagery’ in 1707, it was surely Lahontan, who spent his young adult years in French Canada, learned a Algonquin tongue, and eventually escaped from duty in French Canada by bribing a vessel to take him to Portugal, from which he made his way, avoiding France, to the Netherlands – surely not in a tenured cloud, but probably paying carriage drivers and staying in flea infested inns where every night’s sleep was among the hard sociological facts.

Mais assez! Now that we have done a little work with a battering ram, let’s get down to Lahontan’s life.

Saturday, February 14, 2009

The myth of the noble European

It is, of course, much too late in the day to call back the myth of the myth of the noble savage.

Curiously, attacking the myth of the noble savage seems to be a sport that every generation of historians engage in. Yet, the sport is curiously foreshortened, on the principle of the White magic: As without, so NOT within. The White magic is so powerful that the historians who operate within this principle seemingly are unaware of it – unaware that they are taking as a norm a certain view of European “civilization” which, in actuality, was a rare thing in 16th and 17th century Europe. In fact, it might not be a thing at all.

Some progress here has been made. As Terry Ellingson has pointed out, the term noble did not originally mean “morally elevated” when applied to the Indians. The first appearance of the phrase “noble savage” in English occurs early in the 17th century, in a translation of Marc Lescarbot’s account of French Canada. Why did Lescarbot call the Indians he met noble? Because they hunted, a privilege legally reserved, with some exceptions, to the nobility.

“Upon this privilege is formed the right of hunting, the noblest of all rights that be in the use of man, seeing that God is the author of it. And therefore no marvel if Kings and their nobility have reserved it unto them, by a well-concluding reason that, if they command unto men, with far better reason may they command unto beasts…

Hunting, then, having been granted unto man by a heavenly privilege, the savages through all the West Indies do exercise themselves therein without distinction of persons, not having that fair order established in these parts whereby some are born for the government of the people and the defense of the country, others for the exercising of arts and the tillage of the ground, in such sort that by a fair economy everyone liveth in safety. [Quote Ellingson, 2001: 23]

However, among the mass of accounts of the savage (accounts that are invaluable as records of the first encounter, which were subsequently – and anachronistically - criticized from a latter vantage point, by which time disease, warfare, trade and technology had done their work), there soon appeared a divide, at least among the French. The main French writers were Jesuits, and as an early twentieth century historian, Gilbert Chinard, remarked, the Jesuits were torn between the Christian imperative to depict heathen monsters, and a classical training that allowed them to spot the eerie congruities between classical Mediterranean civilizations and the Indian peoples. Et ego in arcadia was alive beneath the cassock. Hence, a dualism in the representation of the savage.

This, then, is one layer of the myth. Another layer – a layer that has to do with our principle, and the building of the myth of the myth of the noble savage – involves movements which were happening on both sides of the Atlantic at the same time. Take, for instance, the privatization of women.

Jesuits settled among the Montagnais-Naskapi people in the 1650s and 1660s, and left descriptions of this tribe of Algonquin speaking hunter gatherers who they encountered on the banks of the St. Lawrence river. These reports are summed up by Karen Anderson as follows:

In the early years of their contact with the Jesuits, Montagnais-Naskapi men and women were reported to have had an equal right to free choice in marriage and divorce and to initiate sex or to reject a suitor. Both men and women controlled their own work, and the Jesuits remarked that both knew just what they were supposed to do:”Neither meddles with the other.” Women decided when to move camps. The choice of plans, of undertakings, of plans, of journeys, of winterings,” the Jesuit missionary Paul Le Jeune reported, “lies in nearly every instance in the hands of the housewife.” Men left the arrangements of household affairs to the women, who distributed both their own and their husband’s produce without any interference. “I have never seen my host,” Le Jeune commented, “ask a giddy young women that he had with him what became of the provisions, although they were disappearing very fast.” “Women,” he further remarked, “have great power… A man may promise you something and if he does not keep his promise, he thinks himself sufficiently excused if he tells you that his wife did not wish him to do it.”

All this was soon to change with the Jesuits’ plan to convert the Montagnais-Naskapi to Christianity and to turn them into settled agriculturalists and, ultimately, French citizens.”

[Anderson, Commodity Exchange and Subordination: Montagnais-Naskapi and Huron Women, 1600-1650 Karen Anderson, Signs, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 48-62]

…

If we look at a history of women in, say, England during the same period, one finds the same process at work. Alice Clarke, in her seminal The Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century (1919) records the complex process by which women were both forced out of trades and traditional routines in agriculture and urban areas, while at the same time laborers in agriculture and urban trades were being squeezed. This resulted in the inevitable disjunction between the necessity to work – for women – and the image that working outside of the home was shameful – for women.

Thus, where Allan records an increase in the brutality to which women of the Montagnais-Naskapi were subjected (a social fact that rides in tandem with the special resistance of Indian women in the St. Lawrence valley to Christianity - contra the myth of Christian missionaries coming in on humanizing missions, women saw very well that the death of the beliefs of the culture was the end of life as they knew it), Clarke records the expulsion of poor women from the social body in England:

“No one doubted that it was somebody's duty to care for the poor, but arrangements for relief were strictly parochial and the fear of incurring unlimited future responsibilities led English parishioners to strange lengths of cruelty and callousness. The fact that a woman was soon to have a baby, instead of appealing to their chivalry, seemed to them the best

reason for turning her out of her house and driving her from the village, even when a hedge was her only refuge.

The once lusty young woman who had formerly done a hard day's work with the men at harvesting was broken by this life. It is said of an army that it fights upon its stomach. These women faced the grim battle of life, laden with the heavy burden of childbearing,

seldom knowing what it meant to have enough to eat. Is it surprising that courage often

failed and they sank into the spiritless, dismal ranks of miserable beings met in the pages of Quarter Sessions Records, who are constantly being forwarded from one parish to another.

Such women, enfeebled in mind and body, could not hope to earn more than the twopence a day and their food which is assessed as the maximum rate for women

workers in the hay harvest. On the contrary, judging from the account books of the period, they often received only one penny a day for their labour. Significant of their feebleness is the Norfolk assessment which reads, " Women and such impotent persons

that weed corne, or other such like Labourers 2d with meate and drinke, 6d without." 1 Such wages may have sufficed for the infirm and old, but they meant starvation for the woman with a young family depending on her for food. And what chance of health and

virtue existed for the children of these enfeebled starving women?” [89]

Once your eyes are opened by black magic to the communication of within and without, one notices a continuity of movements in the Transatlantic communities. This isn’t to say that the movements were entirely in synch. For instance, George Eisen has picked up accounts of sports, among the Indians, that indicate a sense of fair play still lacking among the English.

“A difference between the European and American style of sporting was readily emphasized by all observers. Sports and games were vigorous and violent affairs among the Indians as well as among the English. Nevertheless, English sports, not yet pervaded by the concept of fair play, were often rough and tumble pastimes in which a wide range of activities bordering on foul play were permitted. Contests of the Indians were conducted in an atmosphere of correctness and mutual respect. Cheating was almost unknown among them. One may compare the contemporary English and French sporting scene with the observation of Father Lalemant. In witnessing a Huron feast, the Jesuit wrote that, "everything was done with such moderation and reserve that - at least, in watching them - one could never have thought that he was in the midst of an assemblage of Barbarians, - so much respect did they pay to one another, even while contending for the victory" (Thwaites 1896-1901:23:221-223). For English spectators, the Indian football was perhaps the most familiar pursuit. The chroniclers repeatedly noted the fact that the English style of the game was violent and sometimes unfair. Spelman's, Strachey's, and Williams' testimonies clearly indicated this fact. Henry Spelman, a member of Captain Smith's expedition to Powhaton's country wrote that the Indians "never fight nor pull one another doune" (Spelman 1872:114). Strachey, the first Secretary of Virginia, also presented a curious comparison between the American and European codes of conduct in the course of the game: "they never strike up one another's heeles, as we do, not accompting that praiseworthie to purchase a goale by such an advantage" (Strachey 1849:84). In 1686, Dunton observed a football game in Agawam. He, too, elaborated on the difference: "Neither were they to apt to trip one anothers heels and quarrel, as I have seen 'em in England" (Dunton 1966:285). A contemporary of Strachey, William Wood, made valuable observations on football as played by the Indians of Massachusetts. His work, New Englands Prospect, is an account of Indian life as the author saw it between 1629 and 1633. "Before they come to this sport, [football] ," wrote the observant Puritan, "they paint themselves, even as when they goe to warre, in pollicie to prevent future mischiefe, because no man should know him that moved his patience or accidentally hurt his person, taking away the occasion of studying revenge.”

[George Eisen, Voyageurs, Black-Robes, Saints, and Indians Ethnohistory, , Vol. 24, No. 3 (Summer, 1977), pp. 191-205]

…

To return, then, to Sade. I have presented Sade so far from Klossowski’s viewpoint. Klossowski sees the system of counter-generality in Sade; what he doesn’t see, or what he mutes, is the Voltairian irony. It is that irony that takes the Christian, rather than the libertine, interpretation of other cultures – or rather, to return to the duality spotted by Chinard, Sade takes the image of the heathen as a monster as his template, even though he was well aware that there was another image – in fact, an image that exists in libertine literature, which made extensive use of ethnography. Here, Sade is not the systematist – instead, he is the traditional enlightenment philosophe. The strategy of the philosophe, from the Persian letters to Voltaire, is to take a normal case – the case for pious belief, for instance - and presses it to the most extreme of conclusions. If God kills his son, isn’t it permitted for human fathers to do the same? If God descended on the Virgin Mary and impregnated her, doesn’t that allow sex outside of wedlock – indeed, doesn’t it allow rape? The system of counter-generality is utopian and messianic; the nuances of irony are cautionary, ambiguous, and novelistic.

But what is this libertine tradition of ethnography? Which takes us back to the Baron Lahontan. As one commentator puts it, Lahontan was Dom Juan in America.

Thursday, February 12, 2009

editorial changes

As some of my readers have remarked, LI’s posts lately are a lot more dense. There is a reason for that. For the past year and a half, I’ve been using this site to do a sort of research note experiment. Usually, when you are researching a book, you type up your notes in various computer folders. But I thought it would be interesting to do this in the open, on a blog. Among other posts, The Human Limit posts would show the way research happens in real time. The principle was really the same as in those 24/7 webcams showing hot hot hot sorority girls dressing, undressing and living the vida loca with dildoes – just, you know, everyday life. Same with my research notes.

THL is not meant to be a philosophy text or a regular history. It is ‘an unofficial view of being’ – to use Wallace Steven’s definition of poetry. I’ve laid down almost all the themes I need, and now I have to start tying them together.

But I’ve decided that this will require a little more order on this blog. Which means that the current affairs commentary has to go. I am finding it too annoying, wading through my always irritated and futile remarks on the oligarchy and their wars, heists, and shiftlessness, looking for this or that thread. So I’ve decided to put them on another blog, called News from the Zona. At the moment, it is little more than template. I’ll have to fill it up eventually with links and stuff.

So, got it? If you want to read the exciting adventures of Baron Lahonte among the Huron, stay tuned on this channel. If you want to read a buncha raven like croakings about our doomed system, go to News from the Zona.

THL is not meant to be a philosophy text or a regular history. It is ‘an unofficial view of being’ – to use Wallace Steven’s definition of poetry. I’ve laid down almost all the themes I need, and now I have to start tying them together.

But I’ve decided that this will require a little more order on this blog. Which means that the current affairs commentary has to go. I am finding it too annoying, wading through my always irritated and futile remarks on the oligarchy and their wars, heists, and shiftlessness, looking for this or that thread. So I’ve decided to put them on another blog, called News from the Zona. At the moment, it is little more than template. I’ll have to fill it up eventually with links and stuff.

So, got it? If you want to read the exciting adventures of Baron Lahonte among the Huron, stay tuned on this channel. If you want to read a buncha raven like croakings about our doomed system, go to News from the Zona.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

As Without, So Within

A history could be written in the time honored manner of horror movies, which take old characters and pit them against each other: Dracula vs. Frankenstein, Godzilla vs. the blob. This episode could be called anti-christ vs. the universal, with both corners suitably decked out in lowrent F/X. Would the philosopher-villain, arising from his unmarked grave among the roots of great oaks – if, indeed, they scattered acorns on his plot as he requested– have found a place at last in B movie limbo? He would, at least, have recognized that the mad scientist was none other than the philosophical fucker, lightly transposed, but still dreaming an outsider cosmology, a metaphysical explanation for every horror. It was the beta ray accident that awoke the dead, Gidget!

The history of the human limit – that is, the history of its erasure - obeys a formula that transforms the old alchemist’s principle, as above, so below, into the principle of universal history – as without, so within. That is, the European encounter with the savages and the barbarians catalyzed the consciousness of savages and barbarians within Europe itself. The savage evokes the peasant, the slave the serf. Universal history, which proceeds by experiments – the plantation, the factory, free trade, representative government, the reservation, the labor camp, etc. – is coded from the beginning to separate the without and the within, even as every discovery produces this two fold effect. The compromise solution was to posit a homunculus within. The ideal Western man.

Sade, however, takes the experiments as narratives, fables, that can be applied, devastatingly, within. On the fair white bourgeois bosom, he applies the slavemaster’s branding iron. As we have pointed out, the ethnographic accounts of tortures and strange customs in the seventeenth century led to an estrangement from the ancients, who could be seen, more and more clearly, in terms of shamans and tribes, and then to a renewal of myth, as the romantics embraced the new barbarous classicism. Sade definitely figures in this history. Klossowski is an excellent guide to the combination of strategies which makes up the Sadeian totality – that self devouring whole. But he misses, we think, the exchanges of the without and the within. The Iroquois and the Kongo.

Klossowski’s work on Sade is a precursot to his work on Nietzsche. In both writers, Klossowski grasps the work done by the notion of the differed totality, or the eternal return of the same. It is this that, within universal history, pushes back against the satisfaction of the modern, that fatal symptom of vulgarity. Marx saw the moment of vulgarity as one of the poles of the modern, in which the determinants are satisfaction and dissatisfaction (thus creating, within the sphere of capitalism, a shadow economy, which delimits the culture of happiness). Neither of those poles is sufficient, for Marx – and thus the revolutionary, or at least the critic of the modern political economy, must oscillate between them, or find some way to exit them entirely. However, it is not so easy to get out of the Artificial Paradise.

Justine’s sorrow was to find this out the hard way.

But to return to Klossowski. Using repetition as a key helps him understand the puzzle of Sade. That puzzle is simple: on the one hand, Sade has staked all pleasure on transgression. On the other hand, a world in which the norms are knocked down – a world in which transgression wins – would seem to be a world without pleasure.

Sade needs a strategy to hold these two things apart. That strategy is outrage.

“If Sade had sought (given that he would have ever been concerned with such a thing) a positive conceptual formulation of perversion, he would have passed alongside of the enigma he sets up; he would have intellectualized the phenomenon of sadism properly so-called. The motive for this is more obscure and forms the nodus of the sadean experience. This motive is outrage, where what is outraged is maintained to serve as a support for transgression.”

We are thus led inevitably to the problem of repetition – for if the point is not, by way of outrage, to overthrow the norms that make for transgression, then outrage has to be become a sort of strategic constant that the mad professor/philosopher-villain manages to make not quite powerful enough to shake the social structure, but still powerful enough to satisfy the desire for staging the transgression. Our monster accepts the terms of the game in order to play the game – the endless repetition of further b movie plots, of an endless “versus”:

“Transgression (outrage) seems absurd and puerile where it does not succeed in resolving itself into a state of affairs where it would no longer be necessary. But it belongs to the nature of transgression that it never be able to find such a state. Transgression is then something other than the pure explosion of energy accumulated by means of an obstacle. Transgression is an incessant recuperation of the possible itself-where the existing state of affairs has eliminated that possible from another form of existence. The possible in what does not exist can never be anything but possible; for if the act were to recuperate this possible as a new form of existence, it would have to transgress it in turn. The possible then eliminated would have to be recuperated yet again. What the act of transgression recuperates from the possible in what does not exist is its own possibility of transgressing what exists.

“Transgression remains a necessity in Sade's experience independent of the interpretation he gives of it. It is not only because it is given as a testimony of atheism that transgression must not and never can find a state in which it could be resolved; the energy must constantly be sur- passed in order to verify its level. It falls below the level reached as soon as it no longer meets an obstacle. A transgression must engender another transgression. But if it is thus reiterated, in Sade it reiterates itself in principle only through one same act. This very act can never be transgressed; its image is each time represented as though it had never been carried out.”

The history of the human limit – that is, the history of its erasure - obeys a formula that transforms the old alchemist’s principle, as above, so below, into the principle of universal history – as without, so within. That is, the European encounter with the savages and the barbarians catalyzed the consciousness of savages and barbarians within Europe itself. The savage evokes the peasant, the slave the serf. Universal history, which proceeds by experiments – the plantation, the factory, free trade, representative government, the reservation, the labor camp, etc. – is coded from the beginning to separate the without and the within, even as every discovery produces this two fold effect. The compromise solution was to posit a homunculus within. The ideal Western man.

Sade, however, takes the experiments as narratives, fables, that can be applied, devastatingly, within. On the fair white bourgeois bosom, he applies the slavemaster’s branding iron. As we have pointed out, the ethnographic accounts of tortures and strange customs in the seventeenth century led to an estrangement from the ancients, who could be seen, more and more clearly, in terms of shamans and tribes, and then to a renewal of myth, as the romantics embraced the new barbarous classicism. Sade definitely figures in this history. Klossowski is an excellent guide to the combination of strategies which makes up the Sadeian totality – that self devouring whole. But he misses, we think, the exchanges of the without and the within. The Iroquois and the Kongo.

Klossowski’s work on Sade is a precursot to his work on Nietzsche. In both writers, Klossowski grasps the work done by the notion of the differed totality, or the eternal return of the same. It is this that, within universal history, pushes back against the satisfaction of the modern, that fatal symptom of vulgarity. Marx saw the moment of vulgarity as one of the poles of the modern, in which the determinants are satisfaction and dissatisfaction (thus creating, within the sphere of capitalism, a shadow economy, which delimits the culture of happiness). Neither of those poles is sufficient, for Marx – and thus the revolutionary, or at least the critic of the modern political economy, must oscillate between them, or find some way to exit them entirely. However, it is not so easy to get out of the Artificial Paradise.

Justine’s sorrow was to find this out the hard way.

But to return to Klossowski. Using repetition as a key helps him understand the puzzle of Sade. That puzzle is simple: on the one hand, Sade has staked all pleasure on transgression. On the other hand, a world in which the norms are knocked down – a world in which transgression wins – would seem to be a world without pleasure.

Sade needs a strategy to hold these two things apart. That strategy is outrage.

“If Sade had sought (given that he would have ever been concerned with such a thing) a positive conceptual formulation of perversion, he would have passed alongside of the enigma he sets up; he would have intellectualized the phenomenon of sadism properly so-called. The motive for this is more obscure and forms the nodus of the sadean experience. This motive is outrage, where what is outraged is maintained to serve as a support for transgression.”

We are thus led inevitably to the problem of repetition – for if the point is not, by way of outrage, to overthrow the norms that make for transgression, then outrage has to be become a sort of strategic constant that the mad professor/philosopher-villain manages to make not quite powerful enough to shake the social structure, but still powerful enough to satisfy the desire for staging the transgression. Our monster accepts the terms of the game in order to play the game – the endless repetition of further b movie plots, of an endless “versus”:

“Transgression (outrage) seems absurd and puerile where it does not succeed in resolving itself into a state of affairs where it would no longer be necessary. But it belongs to the nature of transgression that it never be able to find such a state. Transgression is then something other than the pure explosion of energy accumulated by means of an obstacle. Transgression is an incessant recuperation of the possible itself-where the existing state of affairs has eliminated that possible from another form of existence. The possible in what does not exist can never be anything but possible; for if the act were to recuperate this possible as a new form of existence, it would have to transgress it in turn. The possible then eliminated would have to be recuperated yet again. What the act of transgression recuperates from the possible in what does not exist is its own possibility of transgressing what exists.

“Transgression remains a necessity in Sade's experience independent of the interpretation he gives of it. It is not only because it is given as a testimony of atheism that transgression must not and never can find a state in which it could be resolved; the energy must constantly be sur- passed in order to verify its level. It falls below the level reached as soon as it no longer meets an obstacle. A transgression must engender another transgression. But if it is thus reiterated, in Sade it reiterates itself in principle only through one same act. This very act can never be transgressed; its image is each time represented as though it had never been carried out.”

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

venus' booty

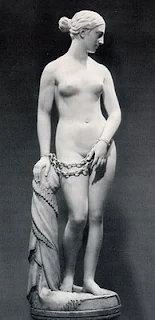

Montesquieu, on his travels through Italy, toured the Uffizi in Florence. He made copious notes, which were published in 1892. He was impressed by the statue known as the Medici Venus, about which he wrote:

Her front side is small, neither too flat nor too round. Her eyes, neither too deep, nor too little, well curved. A head, small. Cheeks, fresh and firm. The part which joins the ear, admirable. The ear, mediocre and well turned. The mouth, big enough for it to be proportionate to the lips. The neck, which is gradually enlarged from the head to the shoulders, and which appears flexible. Beautiful shoulders, but less large than a man’s. Her arms, round and which join to the arm [sic – probably meant hand] by degrees. They have the appearance of firm flesh. Her hands, long and as though made of flesh. Tits, separated, not too low, nor too high. Thighs, admirable: they are elevated a bit from the mons pubis and then diminish little by little to the knee. Her foreleg is admirable: you would think it was flesh. A little more high than the cheeks, you see a little dimple pressing on the back bone, as if from which they are given birth. One knows her attitude – she has a hand upon her tits and the other on her private part, and squats just the littlest bit, as though to hide herself as well as she can in the state she is in. “

After this, he goes through two other Venuses to return to his favorite:

Returning to the Medici Venus – how it serves as a rule, and how what is like it in its proportions is admirable, and what departs from it is bad, one can hardly describe it to much and remark on it.

Behind, just above the cheeks, there is, on each side, two small dimples, and one in the middle, which comes from the back bone; then two small eminences: and at last, the curve down which goes under the coccyx. The cheeks are round, and, on each side of them, there is a little dimple in order to mark their roundness. The cheeks, lower down, make a short curve, and when they are reunited with the thighs, there is a new, little bump. Then, a little hardly noticeable dimple for a new small bump.”

Jacques Guicharnaud has noted that Sade, too, made his tour of Italy, for almost a year, from 1775 to 1776. He too visits the Uffizi. Later, he lends his experience to Juliette and friends. Guicharnaud remarks on the coincidence between Montesquieu and Sade – although of course Montesquieu’s journal had not been published at that time. But the point isn’t the influence but the contrast.

When the heroine, accompanied by Sbrigani and their suite, stops in front of “that superb morsel,” she is gripped by the “sweetest emotin,” and remarks: “it is said that a Greek blazed with passion for a statue… I admit it, I might have imitatied him near that one. The the statue is hardly described at all. Juliette merely points out, very flatly, “the gracious cuves of the bosom and gthe buttocks…

Still in the Uffizi, in front of Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Montesquieu remarks “An admirable Venus; she is lying down naked; you think you’re seeing flesh and the body itself.” Taken literally, this notation is chaste. But before the same painting Juliette gives many more details, without being verbose, and her description leads to an act: when Sbrigani mentioned that “this Venus looked incredibly like Raimonde,” one of their friends, Juliette, in a blaze of passion, “pressed a fiery kiss to the roselike mouth” of the young woman.

To go on with the parallel between these two forms of tourism – or art criticism -: the few works chosen by Juliette are always sources of erotic reactions. Whereas before an ancient Priapus, Montesquieu proves brief and objective, Juliette immediately considers the possibilities – and impossibilities – of the same statue.” (Jacques Guicharnaud,The Wreathed Columns of St. Peter's, Yale French Studies, No. 35, (1965), 31)

Although Sade’s image is of the coldest of the aristocrats, this description is of an extreme vulgarity – Marx’s vulgarity of the modern in all its glory. It resembles Montesquieu less than the famous visit of Gervaise’s wedding party to the Louvre in L’assommoir:

M. Madinier kept quiet in order to manage his effect. He went straight to Ruben’s Kermesse. There, he said nothing, but contented himself with nodding at the canvas and rolling his eyes gaily. The ladies, when they had their noses up into it, uttered little moans; then turned away, very red. The men held them back, jokingly, looking for particularly dirty details.

-- Look-it this!, repeated Boche, this is worth the cost of admission. And here’s one who is puking, and here’s one who is watering the dandylions. And here’s one, o, this one – well, they are a proper lot, they are.

Kant, when he codified the enlightement response to the art work, was drawing on a repertoire which, in part, Sade must have known. Surely Sade was aware of poor old Wincklemann, robbed and murdered by the boy he’d picked up to fuck, all alone in the port of Trieste – it was such a Sadian nuance. But Sade was not interested in art, in any real sense. He could not understand an object that was fundamantally unassimilable to a use. And this is a key to one of Sade’s peculiarities – his invention of the fastforward. True, in the history of porn, the fastforward had to wait for the invention of video and the channel changer. But the temporal foundation of it is already there in Sade. For Montesquieu, the description of the Medici Venus (so eerily reminiscent of advertisements for slaves – or an advertisement for the Venus Hottentot, although she came along long after Montequieu was dead) – is about allowing the object, in the time of the observation, to become what it is, to announce itself, to be seen and more than seen. This time, in turn, served the enlighenment system of the senses. In that system, touch is fundamental. Sight, especially the sight of a sculpture, is in a separate, derivative sense domain. The slow, lubricious stroll around the statue is rooted in the libertine code that allows for a nature without God, but also without man. A nature, that is, removed from the use of men. Of course, one can shift this by some small degree and arrive at the slave holder, and by another degree, at Don Juan.

Sade, however, is not on that channel. He is, at least here, a fast forward libertine, for whom the object is becoming generic, and must have a use. Use will reduce the Greek statue and the Titian to a joke or a proxy for sex. This is Sade’s own vulgarity, prefiguring the bourgeois moment of satisfaction that, really, there is nothing in art. It is either a pinup or a moneymaker. Or – a form of vulgarity perhaps more common in the U..S. - it gives pride to some ethnic group, some gender position; it is critical, it resists, it has a proper political content.

We too hastily identify Sade’s orgies with the Dionysian. But his fast forwards betray him. Calasso points out that Dionysos, unlike the other gods, ‘doesn’t descend on women like a predator, clutch them to his chest, then suddenly let go and disappear. He is constantly in the process of seducing them, because the life forces came together in him. The juice of the vine is his, and likewise the many juices of life. “Sovereign of all that is moist.’ Dionysos himself is liquid, a stream that surrounds us. “Mad for the women,” Nonnus, the last poet to celebrate the god, frequently writes. And with Christian malice Clement of Alexandria speaks of Dionysos as choiropsales, ‘the one who touces the vulva.” The one whose fingers could make it vibrate like the strings of the lyre.” [Calasso, 14]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Love and the electric chair

It is an interesting exercise to apply the method of the theorists to themselves. For instance, Walter Benjamin, who was critiqued by Ador...

-

You can skip this boring part ... LI has not been able to keep up with Chabert in her multi-entry assault on Derrida. As in a proper duel, t...

-

Ladies and Gentlemen... the moment you have all been waiting for! An adventure beyond your wildest dreams! An adrenaline rush from start to...

-

LI feels like a little note on politics is called for. The comments thread following the dialectics of diddling post made me realize that, ...