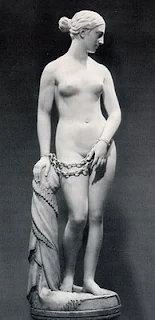

Montesquieu, on his travels through Italy, toured the Uffizi in Florence. He made copious notes, which were published in 1892. He was impressed by the statue known as the Medici Venus, about which he wrote:

Her front side is small, neither too flat nor too round. Her eyes, neither too deep, nor too little, well curved. A head, small. Cheeks, fresh and firm. The part which joins the ear, admirable. The ear, mediocre and well turned. The mouth, big enough for it to be proportionate to the lips. The neck, which is gradually enlarged from the head to the shoulders, and which appears flexible. Beautiful shoulders, but less large than a man’s. Her arms, round and which join to the arm [sic – probably meant hand] by degrees. They have the appearance of firm flesh. Her hands, long and as though made of flesh. Tits, separated, not too low, nor too high. Thighs, admirable: they are elevated a bit from the mons pubis and then diminish little by little to the knee. Her foreleg is admirable: you would think it was flesh. A little more high than the cheeks, you see a little dimple pressing on the back bone, as if from which they are given birth. One knows her attitude – she has a hand upon her tits and the other on her private part, and squats just the littlest bit, as though to hide herself as well as she can in the state she is in. “

After this, he goes through two other Venuses to return to his favorite:

Returning to the Medici Venus – how it serves as a rule, and how what is like it in its proportions is admirable, and what departs from it is bad, one can hardly describe it to much and remark on it.

Behind, just above the cheeks, there is, on each side, two small dimples, and one in the middle, which comes from the back bone; then two small eminences: and at last, the curve down which goes under the coccyx. The cheeks are round, and, on each side of them, there is a little dimple in order to mark their roundness. The cheeks, lower down, make a short curve, and when they are reunited with the thighs, there is a new, little bump. Then, a little hardly noticeable dimple for a new small bump.”

Jacques Guicharnaud has noted that Sade, too, made his tour of Italy, for almost a year, from 1775 to 1776. He too visits the Uffizi. Later, he lends his experience to Juliette and friends. Guicharnaud remarks on the coincidence between Montesquieu and Sade – although of course Montesquieu’s journal had not been published at that time. But the point isn’t the influence but the contrast.

When the heroine, accompanied by Sbrigani and their suite, stops in front of “that superb morsel,” she is gripped by the “sweetest emotin,” and remarks: “it is said that a Greek blazed with passion for a statue… I admit it, I might have imitatied him near that one. The the statue is hardly described at all. Juliette merely points out, very flatly, “the gracious cuves of the bosom and gthe buttocks…

Still in the Uffizi, in front of Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Montesquieu remarks “An admirable Venus; she is lying down naked; you think you’re seeing flesh and the body itself.” Taken literally, this notation is chaste. But before the same painting Juliette gives many more details, without being verbose, and her description leads to an act: when Sbrigani mentioned that “this Venus looked incredibly like Raimonde,” one of their friends, Juliette, in a blaze of passion, “pressed a fiery kiss to the roselike mouth” of the young woman.

To go on with the parallel between these two forms of tourism – or art criticism -: the few works chosen by Juliette are always sources of erotic reactions. Whereas before an ancient Priapus, Montesquieu proves brief and objective, Juliette immediately considers the possibilities – and impossibilities – of the same statue.” (Jacques Guicharnaud,The Wreathed Columns of St. Peter's, Yale French Studies, No. 35, (1965), 31)

Although Sade’s image is of the coldest of the aristocrats, this description is of an extreme vulgarity – Marx’s vulgarity of the modern in all its glory. It resembles Montesquieu less than the famous visit of Gervaise’s wedding party to the Louvre in L’assommoir:

M. Madinier kept quiet in order to manage his effect. He went straight to Ruben’s Kermesse. There, he said nothing, but contented himself with nodding at the canvas and rolling his eyes gaily. The ladies, when they had their noses up into it, uttered little moans; then turned away, very red. The men held them back, jokingly, looking for particularly dirty details.

-- Look-it this!, repeated Boche, this is worth the cost of admission. And here’s one who is puking, and here’s one who is watering the dandylions. And here’s one, o, this one – well, they are a proper lot, they are.

Kant, when he codified the enlightement response to the art work, was drawing on a repertoire which, in part, Sade must have known. Surely Sade was aware of poor old Wincklemann, robbed and murdered by the boy he’d picked up to fuck, all alone in the port of Trieste – it was such a Sadian nuance. But Sade was not interested in art, in any real sense. He could not understand an object that was fundamantally unassimilable to a use. And this is a key to one of Sade’s peculiarities – his invention of the fastforward. True, in the history of porn, the fastforward had to wait for the invention of video and the channel changer. But the temporal foundation of it is already there in Sade. For Montesquieu, the description of the Medici Venus (so eerily reminiscent of advertisements for slaves – or an advertisement for the Venus Hottentot, although she came along long after Montequieu was dead) – is about allowing the object, in the time of the observation, to become what it is, to announce itself, to be seen and more than seen. This time, in turn, served the enlighenment system of the senses. In that system, touch is fundamental. Sight, especially the sight of a sculpture, is in a separate, derivative sense domain. The slow, lubricious stroll around the statue is rooted in the libertine code that allows for a nature without God, but also without man. A nature, that is, removed from the use of men. Of course, one can shift this by some small degree and arrive at the slave holder, and by another degree, at Don Juan.

Sade, however, is not on that channel. He is, at least here, a fast forward libertine, for whom the object is becoming generic, and must have a use. Use will reduce the Greek statue and the Titian to a joke or a proxy for sex. This is Sade’s own vulgarity, prefiguring the bourgeois moment of satisfaction that, really, there is nothing in art. It is either a pinup or a moneymaker. Or – a form of vulgarity perhaps more common in the U..S. - it gives pride to some ethnic group, some gender position; it is critical, it resists, it has a proper political content.

We too hastily identify Sade’s orgies with the Dionysian. But his fast forwards betray him. Calasso points out that Dionysos, unlike the other gods, ‘doesn’t descend on women like a predator, clutch them to his chest, then suddenly let go and disappear. He is constantly in the process of seducing them, because the life forces came together in him. The juice of the vine is his, and likewise the many juices of life. “Sovereign of all that is moist.’ Dionysos himself is liquid, a stream that surrounds us. “Mad for the women,” Nonnus, the last poet to celebrate the god, frequently writes. And with Christian malice Clement of Alexandria speaks of Dionysos as choiropsales, ‘the one who touces the vulva.” The one whose fingers could make it vibrate like the strings of the lyre.” [Calasso, 14]

2 comments:

LI, so there is this quote with which Bataille begins L'Histoire de l'érotisme, part 2 of La part maudite, essai d'économie générale.

The quote is from Léonard de Vinci.

L'acte d'accouplement et les membres dont il se sert sont d'une telle laideur que s'il n'y avait la beauté des visages, les ornements des participants et l'élan effréné, la nature perdrait l'espèce humaine.

...

Amie

L. da Vinci meets Lennie Bruce! Priceless quote, Amie!

Post a Comment