Here’s a translation of the whole text. (I should say, I translated the quotes in the above paragraph myself). It is a remarkable piece – and short, too. It is pretty cool that it is up on the web for those who don’t read French.

Although Bachelard is a long way from Bruno, I don’t think my insertion of him in the chain of figures I'm going to use to talk about misfortunes of the infinite world does him any damage. On the contrary, although Bachelard doesn’t use the anima mundi terminology here, he never hesitated to reach for what some might consider scientifically ‘soft’ terms. His text does reference both older cosmologies and the relativistic image of the universe in physics.

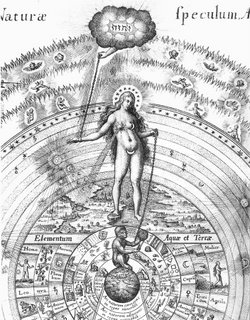

So why do we hear the faint echoes here of Bruno’s anima mundi earth, which is not simply a compound, as Bruno said, of our trash? We’d identify the anima mundi world with that - and here we are making an unjustified leap – world the philosopher has lost. When Bachelard compares the universe of general relativity with the five year plan – a pretty witty comparison – we hear the faint overtones of the infinite world concept. The world whose loss is commoditized, whose atmosphere, oceans and soils have been made totally human over the last two hundred years. The totally human world, a goal shared by capitalist and communist alike, has turned out to be an incredibly successful project. The only non-human factor left in that world – the one factor not subject to the calculation of human use and value – is God. Animal, plant, element – they have all gone into the factory. As for God of the Gods, well, the non-humanity of God doesn’t really provide much of a stumbling block. Every effort is made to process God into the human, to create your nice adorable personal God. Otherwise, fuck him/her/them. The human God is tastier, with 90% less fat.

This weekend, LI liked two posts, one by Smokewriting and one by the friend and foil of this site, Paul Craddick, at Fragmenta Philosophica, that both had to do with the planetary question posed by the IPCC report – although Smokewriting’s post came before the official release of the report. Smokewriting's post welds together two different themes: one, the “risk society” thesis of Ulrich Becker (taken over by Anthony Giddens) that grounded the "third way" rhetoric of the nineties; and two, Hans Jonas’ thesis about the temporal dimension of the capitalist exploitation of nature, where natural resources stand for the future - human future. LI particularly liked this passage:

“Implicit in Beck’s thesis is the idea that the emptying and wholesale exploitation of the future is a structural feature of capital. It is this that generates the sense of having participated in an apocalypse which one failed to notice. Capital does not just extract surplus value from the ongoing present by subjecting it to the repetitive cycles of production, but also extracts it from the living futures of potential embodied in nature. Capitalist production pulls futures into the present and uses them up, but in order to do this it vampirises the past becomings from out of which the world has congealed.”

"The apocalype which one failed to notice" - we tend to see this as the universe that is the infinity of our inattention. It is the 'too big' of all the changes wrought on the biosphere during the twentieth century, the fertilizer dumped, the exhaust from each car, the oddity that transportation became both a major killer in the twentieth century and that the killings were absorbed into the background (while everybody is searching for a cure for malaria and aids, who is searching for a cure for the car accident?), etc.

Paul’s post is less about Capital than about Cost – and the framework in which to measure costs:

[C]onfronted with the reality of climate change and a human role therein, the central question for deliberation - What is to be done? - is an ethical-political one, not primarily a scientific one (not "primarily" because, while sober scientific judgment undoubtedly must inform deliberation, the answer eludes science's competence). In other words, to suppose that science simply "tells" us how to address [climate change] is a blatant category mistake."

Put another way ... even assuming that we could believe, to a reasonable level of certainty, that a certain course of action would ameliorate climate change significantly, it still doesn't follow that it ought to be undertaken. The costs of so doing may be unjustifiable.

I’ll have more to say about this – until you, gentle reader, are sick to death of it – in later posts.