Dark humor, laced with arsenic and old shit, presides over the politics of our time. Obviously. And so it is that the recent Holocaust denier festival, held by Iran’s president, Ahmadinejad , existed very briefly as a moral low point shaming Iran, and was then quickly pimped out by the propagandists of the long war to shame the rest of us. It is an illustrative story, demonstrating that morality melts in the self aggrandizing rhetoric of the belligeranti as quickly as icecubes in hell.

The proper response to the idiot president’s gathering of bedbug scholars and cross eyed KKK men was given by the Iranian population, who voted – within the oppressive limits set by the state – against the accident who governs them. However, it is important to remember this about Ahmadinejad – his idiocy consists, in part, of making for official export what many of America’s Middle Eastern allies prefer to purvey for purely home consumption.

However, that is an unpleasant thing for our current crop of liberationists. Krauthammer recently spelled out the implicit underpinnings of the politics of anti-Semitism by distinguishing the good anti-semites from the bad ones. The good ones are like Nixon – or the current house of Saud. Nixon might have raved against the Jews, and the House of Saud officially condones systematic anti-semitism in the Peninsula – from solemn newspaper series about the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to textbooks that helpfully define Jews as Apes. This might seem, oh, distasteful, but it isn’t so distasteful that our Churchill counterpart in the U.K., brave, brave Tony Blair, can’t occasionally kowtow to the Saudis and pull the plug on bribery investigations and the like, while strewing the Middle East with as much WMD as Britain can sell. And Nixon, of course, saved Israel in 1973.

To find out where a selective moral mindset can lead you, LI suggests reading some of the hothouse maunderings of the late, great Ron Rosenbaum. Like Christopher Hitchens, Rosenbaum has become a convert to neo-conservatism in his declining years, and he now has a forum at a Pajamas Media site that combines the two salient styles of neo-conism: the apocalyptic and the dyspeptic. It is all St. John of Patmos, with a severe ulcer. The second holocaust is around the corner, according to Rosenbaum. Is he talking about the 600,000 Iraqis that have dies so far in the past three years of this unjust and cursed war? No, he’s talking about the Iranian missile system that dances like a poisoned sugarplum in the neocon collective head. Time is running out – the promise of the Bush administration was to promote at least one more war. The real man’s war, the march to Teheran. And, sadly, the clock is ticking and the planes aren’t flying. Rosenbaum is already ahead of the troops, however, proposing that Ahmadinejad be tried for genocide. It is a pre-genocide thing he’s done, a virtual genocide. This is among Rosenbaum’s helpful suggestions about the Middle East. He also seems to suggest that, to prevent a Holocaust, the Palestinians must disappear. Or so it seems – he is against a Tony Judt type state, merging Palestinians and Israelis, and he is against a double state. Perhaps to avoid the Holocaust we have to reinstitute slavery – certainly the disenfranchisement of the Palestinian population that would please Rosenbaum is all about denying those radical Palestinians any political voice at all. To save the village of our Western moral values, we had to burn it down, seems to be the motto.

But when LI wants to drink a refreshing draught of moonlit struck water – to frolic among the truly politically confused – we go to Harry’s Place. The site has continued the most fascinating experiment, dressing up a Thatcherite politics in the ragged language of the most bogus New Left doctrines. At Harry’s Place, Iraq was never occupied, it was liberated. By comrades! comrades one and all.

For them, too, of course, the little matter of the Saudi corruption of British politics, not to speak of the much more violent nature of anti-semitism (and much more totalitarian nature of the political culture) is absolutely on the margins, as they have riveted Iran with their comradely critiques. You get the feeling that these guys have been a bit beat up over the past three years – they aren’t as gung ho on nuking Iran as Rosenbaum (or maybe just a small, lovepat bombing – Rosenbaum is rather vague about how he wants Iran rubbled). But they do love to take the moral high ground, which consists of tying the anti-war movement to the pro-Ahmadinejad, pro Saddam Hussein cadre among us – all twenty of them. This is what happens when morality is an excuse for war, and the war/non-war binary are the only parameters allowed in talking about international relations. Having staked out the big issue – Holocaust denial – and keeping an eagle eye on all the millions of radical pseudolefty Islamofascistophiles who are just itching to do that, they don’t have time to plaster the other eagle eye on, say, our comrades in Basra, who have expressed their own ideas about the Jews by even changing the weekend – they did want to make sure that the Jewish Sabbath was ritually made into a work day, as a sort of symbolic treading over the Jews.

Such are the fruits of the new anti anti-the-wrong-Semites. Let's hope they don't form one of those terrible vintages. Certainly seems like the Grapes of Wrath to me.

“I’m so bored. I hate my life.” - Britney Spears

Das Langweilige ist interessant geworden, weil das Interessante angefangen hat langweilig zu werden. – Thomas Mann

"Never for money/always for love" - The Talking Heads

Wednesday, December 27, 2006

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

pleased with my own self

Casting our eye over the last year, LI feels … good. This has been, of course, a terrible year in the set of terrible years that have made up this decade of complete and utter failure. Our failure to achieve the economic viability of even the lowliest bottomfeeder, which we used to justify, in a half assed way, as the price of art, is no longer justifiable by any criteria. We will long remember and long regret the various outrageous stupidities that have threaded themselves in our moment-to-moment, especially as it looks like we are headed towards streetcorner destitution as surely as the stunned ox slipping down the greased chute is headed for the butcher’s blade. But I would like to think that every life has its little Camelot moment, yes? And so I look back at LI’s past year and a half and like God looking at the green and blue globe he dreamed up on one of eternity’s slower nights, I can say: it is good.

I’ve been five and a half years at the blogging biz, and looking over my back pages, I obviously took some time to figure out what I was doing. For a writer of more traditional narratives, as well as one of more traditional discursive texts, blogging is difficult. It is a text type in the literature of spontaneity that gives us Jules Renand’s journals and Horace Walpole’s letters – not to speak of Malcolm Lowry’s – , which is a literature I have a fondness for. In any work that aspires to literature, one is looking for the real right thing, the moment in which urgency and the mediation of artifice form a more perfect union. And every romantic soul, from Shelley to the Beats, has longed for a way of casting off the mediation, of making good on the adage, first thought, best thought. Unfortunately for the romantics, mediation is indispensable. The path to the urgent moment is necessary, even if, from the subjective viewpoint, it is secondary and always irritating.

But so speaks the classicist mickey within. Of course, LI is living in a society in which boredom is considered the worst quality – to say that a book is boring is to say it has committed a capital offense. Myself, I think the liquidation of boredom in the aesthetic realm is intimately connected to the Gated Community ethos in the social realm, in which the unbought graces of life now come out of a high end catalogue, and are called “pre-owned”. If you don’t know how to be boring – its time, its place, its subtle effects on the unconscious, what it is for, what it tells you about time and solitude – you’ll make a fucking twist of everything. It will just be Man and his faithful tv-set tracking across the void. LI is not for man and his tv set tracking across the void. We are against that shit.

I’m not excursing here – boredom is of course just the thing about spontaneous literature. To have a boring bit of exposition in a novel is tolerable, given other qualities of the novel, and its ultimate interestingness. To have a boring bit of exposition in a letter, however, is much less tolerable. Still, the premise of a letter or a journal is intimacy, which forgives many things. The great letter writers – say, Byron – visibly have a lot of fun writing their three sheets. I’ve been reading the letters of Henry Adams, lately, and it is obvious that the young Adams was modeling himself on letter writers of the past – more than anybody else, Walpole. Obviously, there are parallels between Horace and Henry – both coming from great political families, both being acute observers, and both feeling, acutely, their lack of power as a sign of some failure of character. Adams, in any case, pushes the entertainment too much to the fore. When that happens – when a certain hard to define threshold is crossed – the letter ceases to be intimate, and thus violates its own contract.

Blogging begins by pissing on that contract. I’ve noticed that those who blog for friends start out strong, but quickly peter out. That’s because, well, here it is and don’t say I said it: Hegel is right about some things. The Spirit does obey a pattern – or at least, produces one – and it goes badly with people who try to cross da Spirit. Blogging derives from intimate literature, but is as cold as a motherfucker, in the end. And here’s the paradox: just because LI is so out of sorts with the Spirit of the Age, a pterodactyl among canaries, blogging has been good to us. The reason for that is that complaining – especially complaining from one’s whole existence, complaining that is rooted in a total failure to fit in, in a total complaint levied at the basic social system – is one of those transitional speech forms. It provides a passage from intimacy to anonymity. I have poured more anger and moaning into the ears of debt collectors on the other end of the phone – or, say, the bureaucrats who periodically threaten to turn off my power – than I would dare to do even with a lover. Of course, this is partly cause I’m half mad, but I’m not the half mad guy who talks to himself on the bus. Yet.

But complaining itself is only transitional. And it moves to two extremes – either monomania, or extreme dispersion. Complaining about one thing over and over, or complaining about everything.

Which gets me to why LI is pleased with the past year. It is no secret that, of course, I am a monomaniac. I have the same hardon against the Bush administration that Jeremiah had against the worshippers of Baal. But Jeremiah – or lets say one of the Isaiahs, who are my fave prophets – the Isaiahs were clever prophets. They saw the wickedness of one kingdom or king in terms of a whole vision of what the world is like. They saw early and plainly that the world is balanced between paradise or hell, and one gesture can send it either way. That gesture is the prophetic fiction – the only time anybody listens to the prophet in the Bible, in Jonah, the prophet is naturally pissed off. It is much more fun to predict fire and brimstone than to have people listen to you, change their ways, and avert the fire and brimstone. Dire is sexy – everybody mocks a reformer. But backing up to the point: in the last year and a half I think I’ve successfully found the bigger poetic themes, the motifs I want – madness, the supremacy of war, magic, the synthesis of Michelet’s witchcraft and Marxism – to organize my random bitchery.

I’ve been five and a half years at the blogging biz, and looking over my back pages, I obviously took some time to figure out what I was doing. For a writer of more traditional narratives, as well as one of more traditional discursive texts, blogging is difficult. It is a text type in the literature of spontaneity that gives us Jules Renand’s journals and Horace Walpole’s letters – not to speak of Malcolm Lowry’s – , which is a literature I have a fondness for. In any work that aspires to literature, one is looking for the real right thing, the moment in which urgency and the mediation of artifice form a more perfect union. And every romantic soul, from Shelley to the Beats, has longed for a way of casting off the mediation, of making good on the adage, first thought, best thought. Unfortunately for the romantics, mediation is indispensable. The path to the urgent moment is necessary, even if, from the subjective viewpoint, it is secondary and always irritating.

But so speaks the classicist mickey within. Of course, LI is living in a society in which boredom is considered the worst quality – to say that a book is boring is to say it has committed a capital offense. Myself, I think the liquidation of boredom in the aesthetic realm is intimately connected to the Gated Community ethos in the social realm, in which the unbought graces of life now come out of a high end catalogue, and are called “pre-owned”. If you don’t know how to be boring – its time, its place, its subtle effects on the unconscious, what it is for, what it tells you about time and solitude – you’ll make a fucking twist of everything. It will just be Man and his faithful tv-set tracking across the void. LI is not for man and his tv set tracking across the void. We are against that shit.

I’m not excursing here – boredom is of course just the thing about spontaneous literature. To have a boring bit of exposition in a novel is tolerable, given other qualities of the novel, and its ultimate interestingness. To have a boring bit of exposition in a letter, however, is much less tolerable. Still, the premise of a letter or a journal is intimacy, which forgives many things. The great letter writers – say, Byron – visibly have a lot of fun writing their three sheets. I’ve been reading the letters of Henry Adams, lately, and it is obvious that the young Adams was modeling himself on letter writers of the past – more than anybody else, Walpole. Obviously, there are parallels between Horace and Henry – both coming from great political families, both being acute observers, and both feeling, acutely, their lack of power as a sign of some failure of character. Adams, in any case, pushes the entertainment too much to the fore. When that happens – when a certain hard to define threshold is crossed – the letter ceases to be intimate, and thus violates its own contract.

Blogging begins by pissing on that contract. I’ve noticed that those who blog for friends start out strong, but quickly peter out. That’s because, well, here it is and don’t say I said it: Hegel is right about some things. The Spirit does obey a pattern – or at least, produces one – and it goes badly with people who try to cross da Spirit. Blogging derives from intimate literature, but is as cold as a motherfucker, in the end. And here’s the paradox: just because LI is so out of sorts with the Spirit of the Age, a pterodactyl among canaries, blogging has been good to us. The reason for that is that complaining – especially complaining from one’s whole existence, complaining that is rooted in a total failure to fit in, in a total complaint levied at the basic social system – is one of those transitional speech forms. It provides a passage from intimacy to anonymity. I have poured more anger and moaning into the ears of debt collectors on the other end of the phone – or, say, the bureaucrats who periodically threaten to turn off my power – than I would dare to do even with a lover. Of course, this is partly cause I’m half mad, but I’m not the half mad guy who talks to himself on the bus. Yet.

But complaining itself is only transitional. And it moves to two extremes – either monomania, or extreme dispersion. Complaining about one thing over and over, or complaining about everything.

Which gets me to why LI is pleased with the past year. It is no secret that, of course, I am a monomaniac. I have the same hardon against the Bush administration that Jeremiah had against the worshippers of Baal. But Jeremiah – or lets say one of the Isaiahs, who are my fave prophets – the Isaiahs were clever prophets. They saw the wickedness of one kingdom or king in terms of a whole vision of what the world is like. They saw early and plainly that the world is balanced between paradise or hell, and one gesture can send it either way. That gesture is the prophetic fiction – the only time anybody listens to the prophet in the Bible, in Jonah, the prophet is naturally pissed off. It is much more fun to predict fire and brimstone than to have people listen to you, change their ways, and avert the fire and brimstone. Dire is sexy – everybody mocks a reformer. But backing up to the point: in the last year and a half I think I’ve successfully found the bigger poetic themes, the motifs I want – madness, the supremacy of war, magic, the synthesis of Michelet’s witchcraft and Marxism – to organize my random bitchery.

Monday, December 25, 2006

a star! a star!

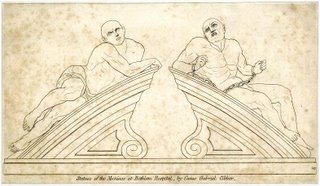

When Simon Fitzmary, the Mayor of London, was fighting in the holy land during the Crusades, he beheld, one lost night, the star of Bethlehem – the very star! Returning to England, in 1236 he founded an asylum – the Church of St. Mary of Bethlehem. It was unique, in that it gave unique shelter to the mad, the first time a public institution in Europe had so specialized. In time, the name was whittled down to Bethlem, and by Shakespeare’s time it had become Bedlam.

And so it was that the rider on the highway is overthrown by the raven, the beast slouches east in the ditch, and poor Jesus o’ Bedlam was born…

Merrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrryyyyyyyyyyyyyyy Christmasssssssssssss

Sunday, December 24, 2006

nostrodamus/LI

A bad policy is one that is so structured that it cannot even exploit advantageous opportunities. By that definition, America’s policy in the Middle East is a magnitude more than bad. This week showcased the cul de sac into which Americans have been lead by the Bush White House.

Given a more rational order of things, this should have been a good week for American foreign policy. Iranian elections struck a heavy blow at the rightwing populism of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. In the Iranian setting, he is proving to be even worse than he seemed at first. His attempt to straddle the contradictions of social and cultural repression and economic expansion – not that these are always in contradiction with each other, but, in Iran’s present case, they certainly are – has failed; his primitive notion of economics to begin with has fatally limited him; and his appeal to a core base has alienated the rest of the country. So Ahmadinejad, like Bush, is becoming a leader/minority.

However, this good news for the Americans can’t get past the American media filter. Since it has been decided that Iran is a dictatorship, run by mad mullahs (as distinguished from the sweet, kindly mullahs that the U.S. has been appealing to, in the Islamic Republic of Iraq, to overthrow the democratically elected leadership), the press can’t even recognize the election. To do so would, after all, put in question the democratic swindle – which was underlined by a mad Blair appealing to dictatorial Gulf emirates to march, oh so democratically, against Iran, even as he was bowing to the Saudi princes and suppressing investigation into the astonishing briberies that have accompanied the British attempt to litter the Middle East with the weapons of mass destruction. This is a familiar pattern – having long ago decided on an absolutist program of hegemony in the Middle East, the U.S. (and, as always, Blair should be viewed as an American subaltern, his rank somewhat below an under undersecretary in the Department of Agriculture) has frozen itself into a posture in which it is impossible to accept anything but total victory – the emplacement, everywhere, of U.S. dominated allies in the Middle East - or defeat. The odds are heavily on defeat.

A sane U.S. foreign policy would recognize a few things. One of them is that the U.S. does not have the moral upper hand on the nuclear issue in the Middle East. Israel practically announced what everybody knows this week – it has a reserve of atomic weapons. How did it get those weapons? Nuclear proliferation happened, here, illegally. The criminal culprit was – the U.S.A. In fact, the powers that managed to get nuclear materials to Israel in the sixties were breaking U.S. domestic law as well. There is a plaque to James Jesus Angleton in Israel, as well there should be. That crazy as a bedbug CIA man handled the Israeli “account’ at the agency, and decided unilaterally to supply the country with atomic weapons. One of the loopier decisions of the D.C. right. Iran may not go for building nuclear weapons – for all the Sturm and Drang, there’s no evidence that they are. If they want to, of course, they have access to Pakistan – with whom they had a very cordial meeting, this week, in the course of which Pakistan announced its aid to Iran’s energy program. This is the same Pakistan that U.S. administrations have tied themselves to now since the seventies, and received, in return – a base to organize jihadism as an international force, a secret service that set up the Taliban and aided Al Qaeda, and a government that has set aside a reservation for Al Qaeda and the Taliban for the last three or four months, reproducing the conditions in Afghanistan in 2000, as Al Qaeda prepared for its big adventure.

But of course, this happens invisibly right before our eyes. The agent of invisibility is language – Pakistan becomes democratic because the U.S. papers call it democratic, Iran becomes a tyranny because the U.S. papers say it is a tyranny, and so on. Currently, the Bush administration’s notion that the Badr brigade represents ‘moderates’ is going down like chocolate milk in the media. By moderate, we are not exactly sure what is meant: do they mean that when Badr brigade members take out the drill, plug it in, and insert the whirling drill bit in the eye socket of some kidnapped Iraqi, that the militia man only pressed down very gently as the liquid eye matter is scattered over the victim’s cheeks and chin? Or is it that the Badr brigade lets the man freely scream as the drill bit plunges into the brain, instead of using tape over his mouth as those bad, bad Sadr people do? LI, moral relativists that we are, doesn’t see the vital, freedom loving part of the Badr program. But of course, we are so morally confused that we think the Vice President was inciting genocide for floating a memo suggesting that the U.S. ‘eliminate’ the Sunnis in Iraq, thus competing with Ahmadinejad for the ‘morally depraved’ part of the competition in the Mr. Rebel in Chief contest. Of course, it may be that this is soft genocide, a moderate position in which certain Sunni children will be allowed to live, as long of course as they agree to the flat tax, but LI is such a blame America firster that we find this unacceptable. Imagine!

This week is no doubt a foretaste of things to come. 2007 should be an even more disastrous year for the U.S. in the Middle East. As we’ve consistently said over the past two years, the chance of the U.S. attacking Iran is low. The Bush administration is surprising – it has explored whole new dimensions of fucking up – and it could surprise us about this issue. After all, the Nixon administration decided, in spite of the evident unpopularity of the Vietnam war, and knowing that they had lost it, to encroach into Cambodia and Laos. But Cambodia and Laos didn’t produce oil, or buy the latest air defense missiles from Russia. Besides which, there is the financial question. In the next couple years, there are about 400 billion dollars in privatization projects on the table in the Middle East, according to the WSJ. And nobody wants these babies fucked up. The Carlyle group is already very heavily into trying to become financier and buyer. What would fuck up the privatizations is an inflamed populace, which might not, to begin with, like the idea of foreign countries buying their water, power, telephone, and other firms. Baby Bush might not want to listen to Daddy, but other people in his administration are looking forward to whoring themselves out in the private sphere for big bucks after their ripoff service with the government is done. These people are going to restrain Baby Bush’s tantrums, we think.

Given a more rational order of things, this should have been a good week for American foreign policy. Iranian elections struck a heavy blow at the rightwing populism of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. In the Iranian setting, he is proving to be even worse than he seemed at first. His attempt to straddle the contradictions of social and cultural repression and economic expansion – not that these are always in contradiction with each other, but, in Iran’s present case, they certainly are – has failed; his primitive notion of economics to begin with has fatally limited him; and his appeal to a core base has alienated the rest of the country. So Ahmadinejad, like Bush, is becoming a leader/minority.

However, this good news for the Americans can’t get past the American media filter. Since it has been decided that Iran is a dictatorship, run by mad mullahs (as distinguished from the sweet, kindly mullahs that the U.S. has been appealing to, in the Islamic Republic of Iraq, to overthrow the democratically elected leadership), the press can’t even recognize the election. To do so would, after all, put in question the democratic swindle – which was underlined by a mad Blair appealing to dictatorial Gulf emirates to march, oh so democratically, against Iran, even as he was bowing to the Saudi princes and suppressing investigation into the astonishing briberies that have accompanied the British attempt to litter the Middle East with the weapons of mass destruction. This is a familiar pattern – having long ago decided on an absolutist program of hegemony in the Middle East, the U.S. (and, as always, Blair should be viewed as an American subaltern, his rank somewhat below an under undersecretary in the Department of Agriculture) has frozen itself into a posture in which it is impossible to accept anything but total victory – the emplacement, everywhere, of U.S. dominated allies in the Middle East - or defeat. The odds are heavily on defeat.

A sane U.S. foreign policy would recognize a few things. One of them is that the U.S. does not have the moral upper hand on the nuclear issue in the Middle East. Israel practically announced what everybody knows this week – it has a reserve of atomic weapons. How did it get those weapons? Nuclear proliferation happened, here, illegally. The criminal culprit was – the U.S.A. In fact, the powers that managed to get nuclear materials to Israel in the sixties were breaking U.S. domestic law as well. There is a plaque to James Jesus Angleton in Israel, as well there should be. That crazy as a bedbug CIA man handled the Israeli “account’ at the agency, and decided unilaterally to supply the country with atomic weapons. One of the loopier decisions of the D.C. right. Iran may not go for building nuclear weapons – for all the Sturm and Drang, there’s no evidence that they are. If they want to, of course, they have access to Pakistan – with whom they had a very cordial meeting, this week, in the course of which Pakistan announced its aid to Iran’s energy program. This is the same Pakistan that U.S. administrations have tied themselves to now since the seventies, and received, in return – a base to organize jihadism as an international force, a secret service that set up the Taliban and aided Al Qaeda, and a government that has set aside a reservation for Al Qaeda and the Taliban for the last three or four months, reproducing the conditions in Afghanistan in 2000, as Al Qaeda prepared for its big adventure.

But of course, this happens invisibly right before our eyes. The agent of invisibility is language – Pakistan becomes democratic because the U.S. papers call it democratic, Iran becomes a tyranny because the U.S. papers say it is a tyranny, and so on. Currently, the Bush administration’s notion that the Badr brigade represents ‘moderates’ is going down like chocolate milk in the media. By moderate, we are not exactly sure what is meant: do they mean that when Badr brigade members take out the drill, plug it in, and insert the whirling drill bit in the eye socket of some kidnapped Iraqi, that the militia man only pressed down very gently as the liquid eye matter is scattered over the victim’s cheeks and chin? Or is it that the Badr brigade lets the man freely scream as the drill bit plunges into the brain, instead of using tape over his mouth as those bad, bad Sadr people do? LI, moral relativists that we are, doesn’t see the vital, freedom loving part of the Badr program. But of course, we are so morally confused that we think the Vice President was inciting genocide for floating a memo suggesting that the U.S. ‘eliminate’ the Sunnis in Iraq, thus competing with Ahmadinejad for the ‘morally depraved’ part of the competition in the Mr. Rebel in Chief contest. Of course, it may be that this is soft genocide, a moderate position in which certain Sunni children will be allowed to live, as long of course as they agree to the flat tax, but LI is such a blame America firster that we find this unacceptable. Imagine!

This week is no doubt a foretaste of things to come. 2007 should be an even more disastrous year for the U.S. in the Middle East. As we’ve consistently said over the past two years, the chance of the U.S. attacking Iran is low. The Bush administration is surprising – it has explored whole new dimensions of fucking up – and it could surprise us about this issue. After all, the Nixon administration decided, in spite of the evident unpopularity of the Vietnam war, and knowing that they had lost it, to encroach into Cambodia and Laos. But Cambodia and Laos didn’t produce oil, or buy the latest air defense missiles from Russia. Besides which, there is the financial question. In the next couple years, there are about 400 billion dollars in privatization projects on the table in the Middle East, according to the WSJ. And nobody wants these babies fucked up. The Carlyle group is already very heavily into trying to become financier and buyer. What would fuck up the privatizations is an inflamed populace, which might not, to begin with, like the idea of foreign countries buying their water, power, telephone, and other firms. Baby Bush might not want to listen to Daddy, but other people in his administration are looking forward to whoring themselves out in the private sphere for big bucks after their ripoff service with the government is done. These people are going to restrain Baby Bush’s tantrums, we think.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

IT's pig metaphysics

LI’s readers are, presumably, the same people who read Infinite thought. For those who haven’t read IT’s prolegomena to all future pig metaphysics, go here.

“What we have to understand, as a matter of some urgency, is that the transcendental pig is our friend, just as the empirical pig is our lunch.”

“What we have to understand, as a matter of some urgency, is that the transcendental pig is our friend, just as the empirical pig is our lunch.”

the passion for ascendancy

“The good Samaritan he’s dressing

He’s getting ready for the show…”

Mark Danner begins his NRYB essay (see last post) with an exemplary historiette concerning a young State Department employee in Falluja who reminds him of a:

“… young Kennan's reincarnation in the person of a junior State Department official: a bright, aggressive young man who spent his twenty-hour days rumbling down the ruined streets in body armor and helmet with his reluctant Marine escorts, meeting with local Iraqi officials, and writing tart cables back to Baghdad or Washington telling his bosses the truth of what was happening on the ground, however reluctant they might be to hear it. This young diplomat was resourceful and brilliant and indefatigable, and as I watched him joking and arguing with the local sheikhs and politicos and technocrats —who were meeting, as they were forced to do, in the American bunker —I thought of the indomitable young Kennan of the interwar years, and of how, if the American effort in Iraq could ever be made to "work," only undaunted and farseeing young men like this one, his spiritual successor, could make it happen.”

This was in the days leading up to the vote on the Constitution. You will remember that Falluja is a mainly Sunni city. It was also razed by American troops in November, 2004. The inhabitants, returning to the ruins of their home, are treated like parolees in a work camp by the Americans. A little background for what the young Kenner told Danner: “And so as I sat after midnight on the eve of the vote, scribbling in my notebook in the dimly lit C-Moc bunker as the young diplomat explained to me the intricacies of the politics of the battered city, I was pleased to see him suddenly lean forward and, with quick glances to either side, offer me a confidence. "You know, tomorrow you are going to be surprised," he told me, speaking softly. "Everybody is going to be surprised. People here are not only going to vote. People here—a great many people here—are going to vote yes.”

Now, only a true mook could think something so unutterably stupid. And yet, the bright young thing almost dazzled Danner into disbelieving his own peepers. Until, of course, the elections showed that the Sunni population voted against the constitution which would basically immiserate them forever) by around 97 percent.

I think that mook was not stupid, but, rather,representative. In LI’s last post, we tried to show that the twilight of the Cold War witnessed a huge economic shift away from the Social Democratic policies of the early Cold War period within the structure created by the Cold War. The end of the Cold War, in a sense, stripped bare these shifts. George Santayana, speaking of patriotism, claimed that, without an ideal, patriotism reduces to a mere “passion for ascendancy.” This was the code of the post-war order. And it is with this code that the U.S. invaded Iraq.

Yet historic forms just don’t pop like the pricked balloons at the end of a children’s birthday party. The intensity of the anti-communist crusade created a whole discourse of righteousness that was extremely potent in America. That discourse no longer had a set object. The idea that our defining anti-thetical is now Islamo-fascism has proven to be a massive flop. Except among a small zombie contingent, Islamofascism hasn’t even entered into the public domain. If you ask around, you will find that the average person hasn’t even heard of it. This shows the common sense of the average person, since, of course, there is no such thing as Islamofascism. The closest actual thing in the world to that hybrid nothing was the government the U.S. conjured up in Iran after overthrowing Mossedeq, since it relied on a heavy contingent of those people around the Pahlavis, in the 1950s, who had ardently supported the Nazis in the 1940s. That ardor was obviously premature anticommunism, and so given a big round of applause by America’s handlers at the time. But there is nothing else on the face of the earth that resembles, in any way, this neo-con anxiety dream.

So… we are left with the passion for ascendancy. The State Department official in Danner’s article walks about in a kind of dream of this passion, as does most of the Bush White House. Mere ascendancy, however, is never sufficient to prompt social action. It generates legitimating stories. These stories are essentially heroic in nature. This, for those who have the eyes to see it, is why the Bush people are so… well, funny. They think of themselves in heroic terms, which is in stark contrast to their incredibly pampered existences and their lifelong avoidance of any real existential risk outside of quailhunting with the gross V.P. These are Chihuahuas dreaming they are lions. They are uniquely disqualified from understanding Iraq -- not because they are unfamiliar with the facts about Iraq, but because their very lifestyles have stifled the faculty of imagination within them. Imagination, for them, is merely projection. Thus, the state department boy projects onto the Iraqis he meets a passion for… well, for the ascension of the state department boy. In their hearts, they all want him to climb the ladder. And to climb the ladder, he needs them to get on board. It is a photo op world, but the reward is that we happy plebes, we rude mechanicals can say, “we knew him when.”

Perhaps the worst thing Chalabi, the prototype D.C. salon Iraqi, ever did was to convince policy-makers that Iraq has the best interests of the U.S. at heart, and in particular the best interests of the 0.00001 percent of the U.S. that owns an AEI card. The ingratitude of the Iraqis must painfully remind these people of other betrayals that strew the path of the meritocratic - like that trusted maid one caught rummaging in the medicine cabinet, pilfering those very expensive mood changing pills. How could she? And just as we gave that made the best hand me down toys and clothes for her squalling brats, in truth, we had given the Iraqis the best of hand me down constitutions -- we trained their savage young men in the best policing techniques, though we did have to laugh behind our hands about how new it all was to them - and we are all about training up an army for them. But of course they know nothing, and in the end you can’t turn your backs on these people.

And so the disappointments of that cadre of people like the eager State department boy have mounted, until we have polite articles in the Sunday NYT debating the pros and cons of Sunni genocide – should we kill one million, or maybe three? The memos, as we know, have been emanating from the V.P.’s office. These articles that are conveniently right next to blasts at the President of Iran for threatening to wipe out Israel, so that we can get the full flavor of the moral arrogance on hand here, a moral arrogance inseparable from the passion for ascendancy.

That passion, we think, is going to get a good and stout fucking in the next year.

He’s getting ready for the show…”

Mark Danner begins his NRYB essay (see last post) with an exemplary historiette concerning a young State Department employee in Falluja who reminds him of a:

“… young Kennan's reincarnation in the person of a junior State Department official: a bright, aggressive young man who spent his twenty-hour days rumbling down the ruined streets in body armor and helmet with his reluctant Marine escorts, meeting with local Iraqi officials, and writing tart cables back to Baghdad or Washington telling his bosses the truth of what was happening on the ground, however reluctant they might be to hear it. This young diplomat was resourceful and brilliant and indefatigable, and as I watched him joking and arguing with the local sheikhs and politicos and technocrats —who were meeting, as they were forced to do, in the American bunker —I thought of the indomitable young Kennan of the interwar years, and of how, if the American effort in Iraq could ever be made to "work," only undaunted and farseeing young men like this one, his spiritual successor, could make it happen.”

This was in the days leading up to the vote on the Constitution. You will remember that Falluja is a mainly Sunni city. It was also razed by American troops in November, 2004. The inhabitants, returning to the ruins of their home, are treated like parolees in a work camp by the Americans. A little background for what the young Kenner told Danner: “And so as I sat after midnight on the eve of the vote, scribbling in my notebook in the dimly lit C-Moc bunker as the young diplomat explained to me the intricacies of the politics of the battered city, I was pleased to see him suddenly lean forward and, with quick glances to either side, offer me a confidence. "You know, tomorrow you are going to be surprised," he told me, speaking softly. "Everybody is going to be surprised. People here are not only going to vote. People here—a great many people here—are going to vote yes.”

Now, only a true mook could think something so unutterably stupid. And yet, the bright young thing almost dazzled Danner into disbelieving his own peepers. Until, of course, the elections showed that the Sunni population voted against the constitution which would basically immiserate them forever) by around 97 percent.

I think that mook was not stupid, but, rather,representative. In LI’s last post, we tried to show that the twilight of the Cold War witnessed a huge economic shift away from the Social Democratic policies of the early Cold War period within the structure created by the Cold War. The end of the Cold War, in a sense, stripped bare these shifts. George Santayana, speaking of patriotism, claimed that, without an ideal, patriotism reduces to a mere “passion for ascendancy.” This was the code of the post-war order. And it is with this code that the U.S. invaded Iraq.

Yet historic forms just don’t pop like the pricked balloons at the end of a children’s birthday party. The intensity of the anti-communist crusade created a whole discourse of righteousness that was extremely potent in America. That discourse no longer had a set object. The idea that our defining anti-thetical is now Islamo-fascism has proven to be a massive flop. Except among a small zombie contingent, Islamofascism hasn’t even entered into the public domain. If you ask around, you will find that the average person hasn’t even heard of it. This shows the common sense of the average person, since, of course, there is no such thing as Islamofascism. The closest actual thing in the world to that hybrid nothing was the government the U.S. conjured up in Iran after overthrowing Mossedeq, since it relied on a heavy contingent of those people around the Pahlavis, in the 1950s, who had ardently supported the Nazis in the 1940s. That ardor was obviously premature anticommunism, and so given a big round of applause by America’s handlers at the time. But there is nothing else on the face of the earth that resembles, in any way, this neo-con anxiety dream.

So… we are left with the passion for ascendancy. The State Department official in Danner’s article walks about in a kind of dream of this passion, as does most of the Bush White House. Mere ascendancy, however, is never sufficient to prompt social action. It generates legitimating stories. These stories are essentially heroic in nature. This, for those who have the eyes to see it, is why the Bush people are so… well, funny. They think of themselves in heroic terms, which is in stark contrast to their incredibly pampered existences and their lifelong avoidance of any real existential risk outside of quailhunting with the gross V.P. These are Chihuahuas dreaming they are lions. They are uniquely disqualified from understanding Iraq -- not because they are unfamiliar with the facts about Iraq, but because their very lifestyles have stifled the faculty of imagination within them. Imagination, for them, is merely projection. Thus, the state department boy projects onto the Iraqis he meets a passion for… well, for the ascension of the state department boy. In their hearts, they all want him to climb the ladder. And to climb the ladder, he needs them to get on board. It is a photo op world, but the reward is that we happy plebes, we rude mechanicals can say, “we knew him when.”

Perhaps the worst thing Chalabi, the prototype D.C. salon Iraqi, ever did was to convince policy-makers that Iraq has the best interests of the U.S. at heart, and in particular the best interests of the 0.00001 percent of the U.S. that owns an AEI card. The ingratitude of the Iraqis must painfully remind these people of other betrayals that strew the path of the meritocratic - like that trusted maid one caught rummaging in the medicine cabinet, pilfering those very expensive mood changing pills. How could she? And just as we gave that made the best hand me down toys and clothes for her squalling brats, in truth, we had given the Iraqis the best of hand me down constitutions -- we trained their savage young men in the best policing techniques, though we did have to laugh behind our hands about how new it all was to them - and we are all about training up an army for them. But of course they know nothing, and in the end you can’t turn your backs on these people.

And so the disappointments of that cadre of people like the eager State department boy have mounted, until we have polite articles in the Sunday NYT debating the pros and cons of Sunni genocide – should we kill one million, or maybe three? The memos, as we know, have been emanating from the V.P.’s office. These articles that are conveniently right next to blasts at the President of Iran for threatening to wipe out Israel, so that we can get the full flavor of the moral arrogance on hand here, a moral arrogance inseparable from the passion for ascendancy.

That passion, we think, is going to get a good and stout fucking in the next year.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

bush at the end of the daisy chain

LI finally got around to reading Mark Danner’s article on Iraq. It is very good. However, one notices that Danner makes the blunders in Iraq stand out against a rather blurry background of America’s foreign policy history, one which exudes a lot of feel good aura but little content. That’s a shame. As we have pointed out before, one of the truly underreported aspects of the American debacle in Iraq goes back to class. Namely, America’s natural tendency to work with the upper class in third world countries was, in Iraq, uniquely negated by the fact that much of that upper class was Sunni, or was perceived to be supportive of Saddam Hussein. Meanwhile, the working class justly saw America as its enemy, since in fact America is always the enemy of the working class in any third world country you want to name. That class aspect only comes into view once one starts viewing America’s foreign policy critically – i.e., once one departs from the consensus about the Cold War that has been dribbled over the establishment like Ronald Reagan’s hair mousse.

You cannot see Iraq, you cannot see the long war, you cannot see 9/11, until you have a clear view of foreign policy past. A timely reminder of what that was all about is given to us by the recent fascistic salute to Jean Kirkpatrick in Hiatt’s Washington Post editorial. To quote it again: “The contrast between Cuba and Chile more than 30 years after Mr. Pinochet's coup is a reminder of a famous essay written by Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, the provocative and energetic scholar and U.S. ambassador to the United Nations who died Thursday. In "Dictatorships and Double Standards," a work that caught the eye of President Ronald Reagan, Ms. Kirkpatrick argued that right-wing dictators such as Mr. Pinochet were ultimately less malign than communist rulers, in part because their regimes were more likely to pave the way for liberal democracies. She, too, was vilified by the left. Yet by now it should be obvious: She was right.”

Kirkpatrick’s terms were, actually, not a change in the weather, but a call to order – a way of reminding the Carter administration of what American policy makers since Truman had always stood for: the implantation, in third world nations, of governments that implemented the Hitler model circa 1938. And, of course, that train of action lead directly to 9/11. There’s a nice reminder of this in Tariq Ali’s concise essay about Pakistan’s history in the LRB. And it calls for some overview.

While Kirkpatrick’s terms simply made visible an old pattern, it is true that the legitimacy of that pattern had been undermined by the obvious U.S. viciousness in Vietnam. Vietnam brought to the surface a critical view of U.S. aims sadly lacking now. It made visible, behind the window dressing of democracy, the real policy of instituting and supporting “authoritarian” regimes. But the critique projected that foreign policy back into the domestic realm in a way that overlooked the contradictions of the system. The foreign policy-maker’s fondness for authoritarian states was in constant tension with America’s political culture. The same liberal newspapers that could support the extension of the liberal program – for instance, disestablishing Dixie apartheid, sustaining the structures of the Keynesian welfare state in health, education, and retirement – could also maintain, without blinking, a network of assumptions shared among foreign correspondents and editors that adopted a wholly other attitude towards third world countries. Eventually, this would have a domestic political effect – cultivating reactionary political economies in Asia and South America was like creating a laboratory for the design of macro-economic policies that would hit the U.S. in the eighties, creating the conditions for a reactionary culture: heavy on military spending, using an unleashed credit sector to weaken the labor movement, with its narrow focus on pay and its inability to understand the new factors brought into the economy by easy credit, the piecemeal de-industrialization, etc., etc. Thomas Friedman, the idiot savant ideologist of neo-liberalism, was right: the whole aim was to take the economy out of politics – to put it wholly in institutional hands unaffected by popular mandate or need.

Thus, the work of the foreign policy establishment in seventies and eighties was to create a new international order of capital, founded on easy credit and pre-30s economic inequality. To buffer the economy completely – to surrender it to investors and business leaders – meant, before anything else, breaking labor’s power decisively. Thus, in the zones outside the ‘democracies’, the ‘fumigation’ began, provided at first by the Hitlerite model – National Security States - and could then become transit points in which loans (for fraudulent, state sponsored projects) and capital flight could come together to bring money into the House – the U.S. and Western Europe.

This structure required the Soviet Union as the enemy that would keep it all together. But that necessity led to a second contradiction in the system – and like one would expect, contradictions lead to innovations. The innovation that the U.S. cultivated, funded, directed and then abandoned happened to be the arming of Islamicists within the structure of fungible National Security States. This is where Tariq Ali’s history comes in as a nice reminder, since the fake history that gives us a fake debate is all about grievances – ah, the framework of victimization, so convenient as a decoy. The real history, which is deeply embedded in the pathological anti-communism and industrial policy of the American foreign policymakers can then be comfortably ignored. The problem, of course, is that it is unignorable – Iraq is a debacle, as Danner says, of the American imagination, or lack of it, but it is also a debacle exposing the way the system has been run, and the antitheses that are now coming, with IEDs and mortar fire, to ruin our ‘freedom loving’ President’s party Middle Eastern bash for himself. There is a sense in which Bush is the victim of a very old and respected Texas fraud – he’s the last link in the daisy chain. A daisy chain is not a mass fuck, in this case – a daisy chain consists of buying a property and selling it to a confederate for an inflated value, who sells it to another confederate for an inflated value, until it is laid off on a mark who, believing these values, shells out some fantastic sum for what turns out to be a world class lemon.

In the case of the Central Asian lemon, as Tariq Ali points out in this overview of Pakistan, the story has roots in the dawn of the independence period. That is when the Free World had need of a subordinate system of non-free gunga din states:

“Pakistan’s first uniformed ruler, General Ayub Khan, a Sandhurst-trained colonial officer, seized power in October 1958 with strong encouragement from both Washington and London. They were fearful that the projected first general election might produce a coalition that would take Pakistan out of security pacts like Seato and towards a non-aligned foreign policy. Ayub banned all political parties, took over opposition newspapers and told the first meeting of his cabinet: ‘As far as you are concerned there is only one embassy that matters in this country: the American Embassy.’”

In Ali’s version, the familiar scenario enfolds – the fakery of pressuring a NSS client into an election that is rigged – by suitable murders, kidnapping and torturing of radicals, students, civilians, etc., etc. – the electing of our man in Karachi, and then the praise showered on him by an adoring American press.

Let’s quote a few grafs that cluster around the Reaganite adventure in creating a jihadi network, arming them, and encouraging them to attack a superpower – a fabulous success that was somehow left out of the funeral orations over the Great Communicator’s corpse:

“Always a bad judge of character, he [Bhutto] had made a junior general and small-minded zealot, Zia-ul-Haq, army chief of staff. As head of the Pakistani training mission to Jordan, Brigadier Zia had led the Black September assault on the Palestinians in 1970. In July 1977, to pre-empt an agreement between Bhutto and the opposition parties that would have entailed new elections, Zia struck. Bhutto was arrested, and held for a few weeks, and Zia promised that new elections would be held within six months, after which the military would return to barracks. A year later Bhutto, still popular and greeted by large crowds wherever he went, was again arrested, and this time charged with murder, tried and hanged in April 1979.

Over the next ten years the political culture of Pakistan was brutalised. As public floggings (of dissident journalists among others) and hangings became the norm, Zia himself was turned into a Cold War hero – thanks largely to events in Afghanistan. Religious affinity did nothing to mitigate the hostility of Afghan leaders to their neighbour. The main reason was the Durand Line, which was imposed on the Afghans in 1893 to mark the frontier between British India and Afghanistan and which divided the Pashtun population of the region. After a hundred years (the Hong Kong model) all of what became the North-Western Frontier Province of British India was supposed to revert to Afghanistan but no government in Kabul ever accepted the Durand Line any more than they accepted British, or, later, Pakistani control, over the territory.”

Then we get into it – although these facts are known, it is always good to have a concise account of how the U.S. fought the Cold War, outside of the purview of the population:

“In 1977, when Zia came to power, 90 per cent of men and 98 per cent of women in Afghanistan were illiterate; 5 per cent of landowners held 45 per cent of the cultivable land and the country had the lowest per capita income of any in Asia. The same year, the Parcham Communists, who had backed the 1973 military coup by Prince Daud after which a republic was proclaimed, withdrew their support from Daud, were reunited with other Communist groups to form the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), and began to agitate for a new government. The regimes in neighbouring countries became involved. The shah of Iran, acting as a conduit for Washington, recommended firm action – large-scale arrests, executions, torture – and put units from his torture agency at Daud’s disposal. The shah also told Daud that if he recognised the Durand Line as a permanent frontier the shah would give Afghanistan $3 billion and Pakistan would cease hostile actions. Meanwhile, Pakistani intelligence agencies were arming Afghan exiles while encouraging old-style tribal uprisings aimed at restoring the monarchy. Daud was inclined to accept the shah’s offer, but the Communists organised a pre-emptive coup and took power in April 1978. There was panic in Washington, which increased tenfold as it became clear that the shah too was about to be deposed. General Zia’s dictatorship thus became the lynchpin of US strategy in the region, which is why Washington green-lighted Bhutto’s execution and turned a blind eye to the country’s nuclear programme. The US wanted a stable Pakistan whatever the cost.

As we now know, plans (a ‘bear-trap’, in the words of the US national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski) were laid to destabilise the PDPA, in the hope that its Soviet protectors would be drawn in. Plans of this sort often go awry, but they succeeded in Afghanistan, primarily because of the weaknesses of the Afghan Communists themselves: they had come to power through a military coup which hadn’t involved any mobilisation outside Kabul, yet they pretended this was a national revolution; their Stalinist political formation made them allergic to any form of accountability and ideas such as drafting a charter of democratic rights or holding free elections to a constituent assembly never entered their heads. Ferocious factional struggles led, in September 1979, to a Mafia-style shoot-out at the Presidential Palace in Kabul, during which the prime minister, Hafizullah Amin, shot President Taraki dead. Amin, a nutty Stalinist, claimed that 98 per cent of the population supported his reforms but the 2 per cent who opposed them had to be liquidated. There were mutinies in the army and risings in a number of towns as a result, and this time they had nothing to do with the Americans or General Zia.

Finally, after two unanimous Politburo decisions against intervention, the Soviet Union changed its mind, saying that it had ‘new documentation’. This is still classified, but it would not surprise me in the least if the evidence consisted of forgeries suggesting that Amin was a CIA agent. Whatever it was, the Politburo, with Yuri Andropov voting against, now decided to send troops into Afghanistan. Its aim was to get rid of a discredited regime and replace it with a marginally less repulsive one. Sound familiar?

From 1979 until 1988, Afghanistan was the focal point of the Cold War. Millions of refugees crossed the Durand Line and settled in camps and cities in the NWFP. Weapons and money, as well as jihadis from Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Egypt, flooded into Pakistan. All the main Western intelligence agencies (including the Israelis’) had offices in Peshawar, near the frontier. The black-market and market rates for the dollar were exactly the same. Weapons, including Stinger missiles, were sold to the mujahedin by Pakistani officers who wanted to get rich quickly. The heroin trade flourished and the number of registered addicts in Pakistan grew from a few hundred in 1977 to a few million in 1987.”

Well, enough for today. I am going to add to this post tomorrow, I hope.

You cannot see Iraq, you cannot see the long war, you cannot see 9/11, until you have a clear view of foreign policy past. A timely reminder of what that was all about is given to us by the recent fascistic salute to Jean Kirkpatrick in Hiatt’s Washington Post editorial. To quote it again: “The contrast between Cuba and Chile more than 30 years after Mr. Pinochet's coup is a reminder of a famous essay written by Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, the provocative and energetic scholar and U.S. ambassador to the United Nations who died Thursday. In "Dictatorships and Double Standards," a work that caught the eye of President Ronald Reagan, Ms. Kirkpatrick argued that right-wing dictators such as Mr. Pinochet were ultimately less malign than communist rulers, in part because their regimes were more likely to pave the way for liberal democracies. She, too, was vilified by the left. Yet by now it should be obvious: She was right.”

Kirkpatrick’s terms were, actually, not a change in the weather, but a call to order – a way of reminding the Carter administration of what American policy makers since Truman had always stood for: the implantation, in third world nations, of governments that implemented the Hitler model circa 1938. And, of course, that train of action lead directly to 9/11. There’s a nice reminder of this in Tariq Ali’s concise essay about Pakistan’s history in the LRB. And it calls for some overview.

While Kirkpatrick’s terms simply made visible an old pattern, it is true that the legitimacy of that pattern had been undermined by the obvious U.S. viciousness in Vietnam. Vietnam brought to the surface a critical view of U.S. aims sadly lacking now. It made visible, behind the window dressing of democracy, the real policy of instituting and supporting “authoritarian” regimes. But the critique projected that foreign policy back into the domestic realm in a way that overlooked the contradictions of the system. The foreign policy-maker’s fondness for authoritarian states was in constant tension with America’s political culture. The same liberal newspapers that could support the extension of the liberal program – for instance, disestablishing Dixie apartheid, sustaining the structures of the Keynesian welfare state in health, education, and retirement – could also maintain, without blinking, a network of assumptions shared among foreign correspondents and editors that adopted a wholly other attitude towards third world countries. Eventually, this would have a domestic political effect – cultivating reactionary political economies in Asia and South America was like creating a laboratory for the design of macro-economic policies that would hit the U.S. in the eighties, creating the conditions for a reactionary culture: heavy on military spending, using an unleashed credit sector to weaken the labor movement, with its narrow focus on pay and its inability to understand the new factors brought into the economy by easy credit, the piecemeal de-industrialization, etc., etc. Thomas Friedman, the idiot savant ideologist of neo-liberalism, was right: the whole aim was to take the economy out of politics – to put it wholly in institutional hands unaffected by popular mandate or need.

Thus, the work of the foreign policy establishment in seventies and eighties was to create a new international order of capital, founded on easy credit and pre-30s economic inequality. To buffer the economy completely – to surrender it to investors and business leaders – meant, before anything else, breaking labor’s power decisively. Thus, in the zones outside the ‘democracies’, the ‘fumigation’ began, provided at first by the Hitlerite model – National Security States - and could then become transit points in which loans (for fraudulent, state sponsored projects) and capital flight could come together to bring money into the House – the U.S. and Western Europe.

This structure required the Soviet Union as the enemy that would keep it all together. But that necessity led to a second contradiction in the system – and like one would expect, contradictions lead to innovations. The innovation that the U.S. cultivated, funded, directed and then abandoned happened to be the arming of Islamicists within the structure of fungible National Security States. This is where Tariq Ali’s history comes in as a nice reminder, since the fake history that gives us a fake debate is all about grievances – ah, the framework of victimization, so convenient as a decoy. The real history, which is deeply embedded in the pathological anti-communism and industrial policy of the American foreign policymakers can then be comfortably ignored. The problem, of course, is that it is unignorable – Iraq is a debacle, as Danner says, of the American imagination, or lack of it, but it is also a debacle exposing the way the system has been run, and the antitheses that are now coming, with IEDs and mortar fire, to ruin our ‘freedom loving’ President’s party Middle Eastern bash for himself. There is a sense in which Bush is the victim of a very old and respected Texas fraud – he’s the last link in the daisy chain. A daisy chain is not a mass fuck, in this case – a daisy chain consists of buying a property and selling it to a confederate for an inflated value, who sells it to another confederate for an inflated value, until it is laid off on a mark who, believing these values, shells out some fantastic sum for what turns out to be a world class lemon.

In the case of the Central Asian lemon, as Tariq Ali points out in this overview of Pakistan, the story has roots in the dawn of the independence period. That is when the Free World had need of a subordinate system of non-free gunga din states:

“Pakistan’s first uniformed ruler, General Ayub Khan, a Sandhurst-trained colonial officer, seized power in October 1958 with strong encouragement from both Washington and London. They were fearful that the projected first general election might produce a coalition that would take Pakistan out of security pacts like Seato and towards a non-aligned foreign policy. Ayub banned all political parties, took over opposition newspapers and told the first meeting of his cabinet: ‘As far as you are concerned there is only one embassy that matters in this country: the American Embassy.’”

In Ali’s version, the familiar scenario enfolds – the fakery of pressuring a NSS client into an election that is rigged – by suitable murders, kidnapping and torturing of radicals, students, civilians, etc., etc. – the electing of our man in Karachi, and then the praise showered on him by an adoring American press.

Let’s quote a few grafs that cluster around the Reaganite adventure in creating a jihadi network, arming them, and encouraging them to attack a superpower – a fabulous success that was somehow left out of the funeral orations over the Great Communicator’s corpse:

“Always a bad judge of character, he [Bhutto] had made a junior general and small-minded zealot, Zia-ul-Haq, army chief of staff. As head of the Pakistani training mission to Jordan, Brigadier Zia had led the Black September assault on the Palestinians in 1970. In July 1977, to pre-empt an agreement between Bhutto and the opposition parties that would have entailed new elections, Zia struck. Bhutto was arrested, and held for a few weeks, and Zia promised that new elections would be held within six months, after which the military would return to barracks. A year later Bhutto, still popular and greeted by large crowds wherever he went, was again arrested, and this time charged with murder, tried and hanged in April 1979.

Over the next ten years the political culture of Pakistan was brutalised. As public floggings (of dissident journalists among others) and hangings became the norm, Zia himself was turned into a Cold War hero – thanks largely to events in Afghanistan. Religious affinity did nothing to mitigate the hostility of Afghan leaders to their neighbour. The main reason was the Durand Line, which was imposed on the Afghans in 1893 to mark the frontier between British India and Afghanistan and which divided the Pashtun population of the region. After a hundred years (the Hong Kong model) all of what became the North-Western Frontier Province of British India was supposed to revert to Afghanistan but no government in Kabul ever accepted the Durand Line any more than they accepted British, or, later, Pakistani control, over the territory.”

Then we get into it – although these facts are known, it is always good to have a concise account of how the U.S. fought the Cold War, outside of the purview of the population:

“In 1977, when Zia came to power, 90 per cent of men and 98 per cent of women in Afghanistan were illiterate; 5 per cent of landowners held 45 per cent of the cultivable land and the country had the lowest per capita income of any in Asia. The same year, the Parcham Communists, who had backed the 1973 military coup by Prince Daud after which a republic was proclaimed, withdrew their support from Daud, were reunited with other Communist groups to form the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), and began to agitate for a new government. The regimes in neighbouring countries became involved. The shah of Iran, acting as a conduit for Washington, recommended firm action – large-scale arrests, executions, torture – and put units from his torture agency at Daud’s disposal. The shah also told Daud that if he recognised the Durand Line as a permanent frontier the shah would give Afghanistan $3 billion and Pakistan would cease hostile actions. Meanwhile, Pakistani intelligence agencies were arming Afghan exiles while encouraging old-style tribal uprisings aimed at restoring the monarchy. Daud was inclined to accept the shah’s offer, but the Communists organised a pre-emptive coup and took power in April 1978. There was panic in Washington, which increased tenfold as it became clear that the shah too was about to be deposed. General Zia’s dictatorship thus became the lynchpin of US strategy in the region, which is why Washington green-lighted Bhutto’s execution and turned a blind eye to the country’s nuclear programme. The US wanted a stable Pakistan whatever the cost.

As we now know, plans (a ‘bear-trap’, in the words of the US national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski) were laid to destabilise the PDPA, in the hope that its Soviet protectors would be drawn in. Plans of this sort often go awry, but they succeeded in Afghanistan, primarily because of the weaknesses of the Afghan Communists themselves: they had come to power through a military coup which hadn’t involved any mobilisation outside Kabul, yet they pretended this was a national revolution; their Stalinist political formation made them allergic to any form of accountability and ideas such as drafting a charter of democratic rights or holding free elections to a constituent assembly never entered their heads. Ferocious factional struggles led, in September 1979, to a Mafia-style shoot-out at the Presidential Palace in Kabul, during which the prime minister, Hafizullah Amin, shot President Taraki dead. Amin, a nutty Stalinist, claimed that 98 per cent of the population supported his reforms but the 2 per cent who opposed them had to be liquidated. There were mutinies in the army and risings in a number of towns as a result, and this time they had nothing to do with the Americans or General Zia.

Finally, after two unanimous Politburo decisions against intervention, the Soviet Union changed its mind, saying that it had ‘new documentation’. This is still classified, but it would not surprise me in the least if the evidence consisted of forgeries suggesting that Amin was a CIA agent. Whatever it was, the Politburo, with Yuri Andropov voting against, now decided to send troops into Afghanistan. Its aim was to get rid of a discredited regime and replace it with a marginally less repulsive one. Sound familiar?

From 1979 until 1988, Afghanistan was the focal point of the Cold War. Millions of refugees crossed the Durand Line and settled in camps and cities in the NWFP. Weapons and money, as well as jihadis from Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Egypt, flooded into Pakistan. All the main Western intelligence agencies (including the Israelis’) had offices in Peshawar, near the frontier. The black-market and market rates for the dollar were exactly the same. Weapons, including Stinger missiles, were sold to the mujahedin by Pakistani officers who wanted to get rich quickly. The heroin trade flourished and the number of registered addicts in Pakistan grew from a few hundred in 1977 to a few million in 1987.”

Well, enough for today. I am going to add to this post tomorrow, I hope.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

No opinion

I believe that if you gave a pollster a gun, and that pollster shot the polled in the leg and asked them if they approved or did not appro...

-

You can skip this boring part ... LI has not been able to keep up with Chabert in her multi-entry assault on Derrida. As in a proper duel, t...

-

Ladies and Gentlemen... the moment you have all been waiting for! An adventure beyond your wildest dreams! An adrenaline rush from start to...

-

LI feels like a little note on politics is called for. The comments thread following the dialectics of diddling post made me realize that, ...