In Uri Eisenzweig’s magisterial Fictions de l’anarchisme, on page 57, mention is made of Clément Duval, who is included among the “mi-révolutionnaires and the illégalistes”. In a footnote, we are told his “affaire” preoccupied anarchist circles in the 1886–1887 period. Eisenzweig’s book is intended to touch on anarchy and the literature of the period, as well as giving us a proto-history of terrorism as a particular discursive device, and Duval was merely a small figure in this theme.

A good book. One review remarked: “Complex analyses — always accompanied by a great attention to the sources, the texts — develops the thesis according to which these provocations [of the anarchist movement] translate a crisis as to the capacity of language to transmit a « realistic » perception of social relations ; a crisis that touched, of course, on the confidence in parliamentary rule, but also, more generally, on the status of communication — thus, of literature…”

So: a name, Clément Duval. I came upon it as an innocent. I know of Sacco and Vanzetti, I know a bit about the Bonnet gang, I know that Carla Tresca was murdered by Stalinists. A little learning, but I come from the Marx side of things, generally. It is only that: lately, I have wondered if maybe it is anarchy, mutual aid as Kropotkin put it, that will save us.

Salvation, which I once thought of as bourgeois mystification, I now think of as a historical necessity. I grow old, I grow old.

I liked the idea of mi-revolutionnaires and illegalists. So I started to research the “affaire Duval.” Which brought me to an address: 31 Rue de Monceau.

A pretty and expensive part of Paris, today. A pretty and expensive part of Paris in the 1880s, too.

I have been thinking about addresses in Paris. I’ve been thinking of city novels and addresses. I’ve been thinking that in the streets of certain cities, certain capitals, there are ghosts. Ghosts of historic events. And ghosts of faits divers. The outlaw event, the irregularity. Didier Decoin wrote: “what seduces us are the “little people” of the fait divers.” In opposition to a history of great events and great people.

An opposition that, like the old regime that forged it, has not entirely crumbled.

In a sense, as my research began to make clear, Clément Duval’s entire life was spent attacking that opposition; which implies, like all such blind and heady attacks, a certain dependence on the opposition.

2.

I’ve come to think there’s a certain guilt about Clément Duval. Not a guilt among the guilty — the powerful, the police, the capitalists, etc. No, a guilt among the comrades. A guilt in the leftwing, anti-statist circles that knew about him.

Octave Mirbeau wrote: “The old world crumbles under the weight of its sins. It will light the bomb that will blow it up. And that bomb will certainly contain neither gunpowder nor dynamite. It will contain the Idea and the Pity: two forces without which one can do nothing.” Mirbeau’s prophecies, of the 1890s apply comprehensively to Clément Duval, but they were written with the famous Ravachol in mind — a much more bloodstained, a much more liminal, a much more psychologically disturbed figure. I believe — or at least the story of Duval has features that make me believe — that he was not only abused by the system — but was, perhaps, set up.

3.

That’s pure speculation on my part. Nobody else says it.

Duval, by profession a locksmith, was a member of the Batignolle Panther, an anarchist group whose choice of totem animal did not, I believe, influence the choice of the same totem for the Black Power militants of the 1960s. However, under the surface, leftist touches leftist, situation situation, courtroom theatre, courtroom theatre. Who knows what rumors Huey Newton might have heard?

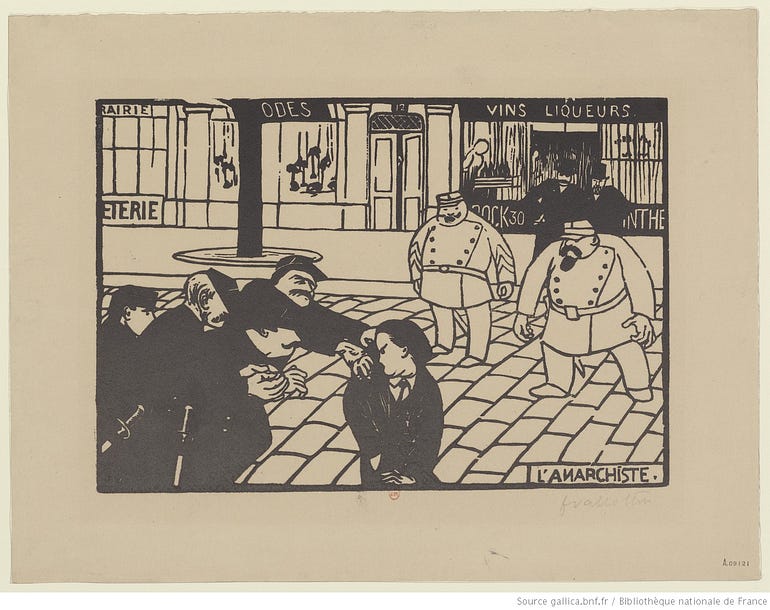

It was in 1886 when the Duval affair reached the Paris papers. Duval and a mysterious man named Turquais or Turquet, resolved to put into practice the slogan, expropriate the expropriators. Proudhon’s phrase, Property is Theft (a maxim that contains the essence of graffiti as the anarchist weapon of choice) had been absorbed into the anarchist community. The “right to theft”, which had, they claimed, been the property of the upper class, was to become the property of those bold enough among the workers to claim it. Thievery on a mass scale — capitalism — was to be met with thievery on an individual scale — anarchy. The target they chose was, to say the least, peculiar: a two story town house in which a fashionable painter, Madame Lemaire, lived and worked. On October 6, 1886, at 31 Rue Monceau, a fire broke out — a fire set by robbers. Let me quote Maitron, the indispensable site for radical history:

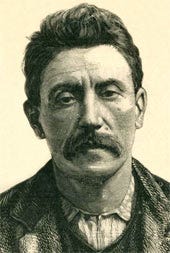

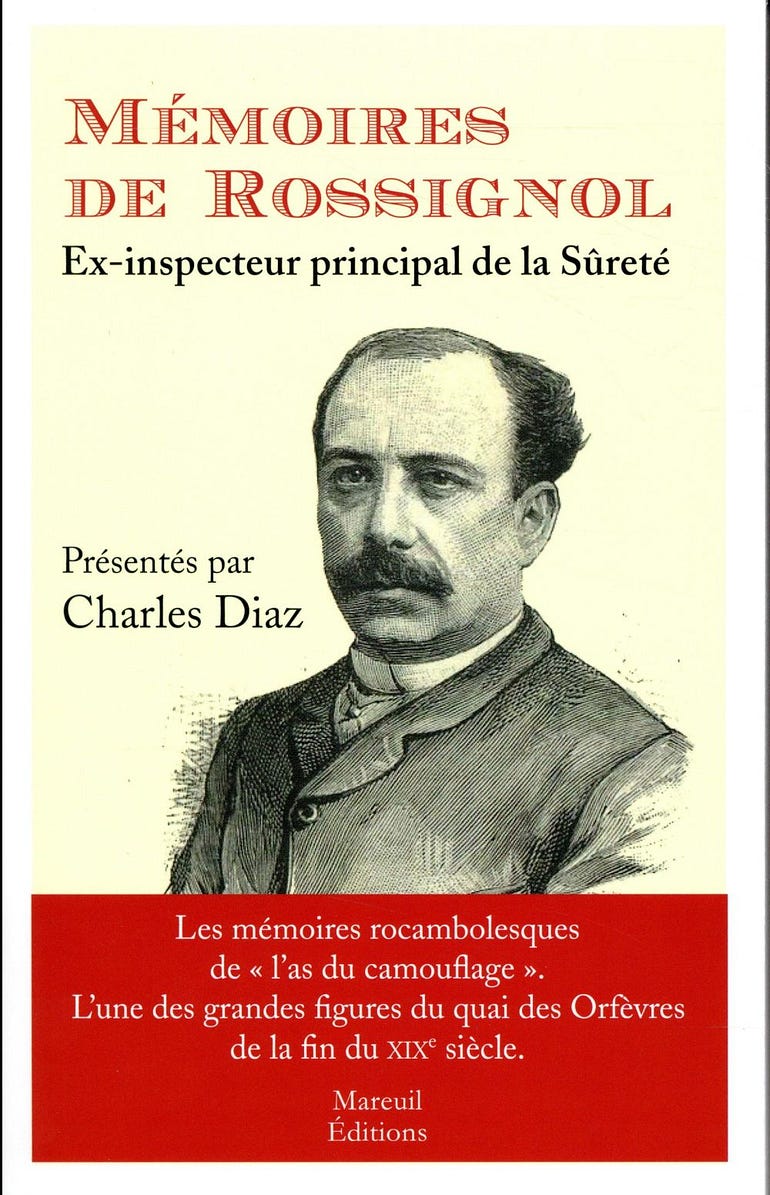

« Some days later, following a raid on a person named Didier, a fence, Clément Duval was arrested — not without having wounded Officer Rossignol with some superficial knife blows — as being the author of the robbery. Imprisoned in Mazas, he wrote on October 24, 1886 to Le Révolté (n° 6, du 12 novembre 1886) to justify himself in the name of the theories he exposed in court.”

In Duval’s memoir, translated into English by Michael Shreve, Duval describes the circumstances that led to him being tried for attempted murder:

“You are accused of the attempted murder of Sergeant Rossignol. When this officer was investigating Didier with the chief of detectives, Didier’s wife pointed you out as Duval to the officer. He asked you to follow him to talk to the chief of detectives. You answered that you had no business with him and he wasn’t one of your friends. Seeing this, the officer identified himself as a sergeant of the police and arrested you in the name of the law. You answered him: ‘Ah! Scum, in the name of freedom I’ll strike you down!’ And you stabbed him eight times with a handmade dagger, intending to kill him.”

“I only struck Sergeant Rossignol twice and not eight times. If I’d stabbed him eight times, being all worked up by the surprise at being arrested as I was, he would probably not be here to testify. It was a scratch, a scrape that he got when we fell off the sidewalk. Unfortunately, he dragged me down with him in his fall, otherwise neither he nor Officer Pelletier, who was with him, would have arrested me.”

“So, you would have killed them both?”

“No, I would have defended my freedom. But I couldn’t. Officer Pelletier right away took advantage of my fall by grabbing me by my throat and my private parts; and Rossignol was able to get hold of my right thumb and bite it.”

4.

A certain air of farce. Officer Rossignol. Officer Nightingale. The grabbing of the private parts, the biting of the thumb.

5.

Albert Bataille, in his early thirties at the time, covered the trial for the Figaro. Bataille was trained as a lawyer. Among his colleagues, he was known for his energy and persistence: “Leaning his head over his pad of paper, pen in hand, he would report on what he was seeing for five or six hours at a time. … He grasped on the fly sudden incidences that would cause a shock, he’d extract from interrogatories everything that was pertinent, susceptible to enlighten the reader…” In France, Bataille was known for a report maintaining that journalists should be trained as such, at the higher education level. He died in 1899 from a heart attack: “ A little tired the last two or three days”, read the report in the Figaro, “he had happily passed the evening at home, with his family. At one in the morning the first symptoms of the sickness declared themselves. His entourage, and he himself, at first believed that it was only a not very serious feeling of discomfort, and soon, after taking some care, his good humor returned. It was only around seven in the morning that a new crisis occurred. He got up suddenly, then, regaining his bed, at the insistence of his poor frightened wife, he told her simply, I am lost, and died in her arms.”

Bataille described Duval like this, on January 14, 1887: “Duval is a bad boy around thirty years old, hairy, with an evil squint, a bushy moustache, a line in bibulous talk, a sinister clown who posed himself before the jury without seeing that he was playing for his head.”

Posed. A threatrical term. One used by Duval himself — he spoke, once, about being “posed” — playing the role of — the accused. The dramaturgy leaks through the legal ritual.

Yet, Bataille’s account of Duval’s street eloquence is not without a certain hint of admiration. Duval was not a buffoon, a sinister clown, however much his working class manners insulted the dignity of a courtroom that was, in its etiquette, a redoubt of esoteric and feudal gestures. His speech to the jury after they found him guilty is both moving and, for the readers of Figaro, where it appeared in Bataille’s reporting, a threat.

“I have to tell you that I am not a thief, but a rebel. I have to tell you why I am an anarchist. My lawyer has posed me here before you as the accused. But I pose myself as the accuser. If you want the head of an anarchist, here it is, take mine. But I have the right to turn to bourgeois society and ask it to account for itself. Theft, on our part, is restitution. In pillaging, as you put it, the town house of Madame Madeleine Lemaire, I committed an act of anarchy.

I’ve given the people a lesson in the deed…. I do not recognize your law. I am not a defendant — I am an avenger!”

6.

Yet was this locksmith an avenger?

Or a dupe?

For his tussle with a policeman, his stealing of silver and jewellery, and for setting a fire that burned “a portrait of Lemaire by Chaplin, a piano, and an umbrella painted by a young miss,” Duval was given the death penalty. However, because this sentence caused a stir — it is a little much to guillotine a man for scratching a plainclothes policeman and taking some thousands of dollars in jewellery that was quickly recovered — it was changed to life in the prison colony of Guyana, another sort of death sentence. Duval’s speeches had been too well reported in the papers to allow him to serve five years in some prison in France. Duval himself published, or had someone publish, a little pamphlet containing his defence. In his memoir, he claimed that 50,000 of these pamphlets were sold. So: better to bury him in the French overseas concentration camp system. Like the much more famous Henri Charrière — Papillon — he managed in the end, after 18 years, to escape his prison in Guyana. Papillon became a movie, written by Dalton Trumbo, the ex communist. In Marianne Enckell’s introduction to Duval’s memoirs, Duval is called an anti-Papillon — Papillon was, after all, a cop stooge who bowed down to the authorities, snitched, and snubbed his fellow prisoners. Duval, that hirsute locksmith, was far more guilty in the eyes of bourgeois society: he threatened it with the bomb. His Hollywood category is plainly villain.

7.

“… and Clement Duval, who made his name in 1886 by knifing a police officer.” Beverly Gage, The Day Wall Street Exploded: the story of America in its first age of Terror.

:… A burglar named Clement Duval, who stole from a wealthy Paris residence, was transformed into Comrade Duval.” John Merriman, The Dynamite Club: How a Bombing in Fin-de-siècle Paris Ignited the Age of Modern Terror.

“… Clement Duval, a notorious robber who justified his profession as a redress of social oppression.” Louis Patsouras, Crucible of Socialism.

Inglory is one of the great tools of bourgeois historiography. When that tool is seized — as in the recent case of the 1619 affair — there is a veritable explosion in the club. It is as if by some inadvertence, some failure of the police -the cultural police — Clément Duval or his type — mounts to the judge’s seat and issues sentence. It is as if the avenger were at the door. Clément Duval is a perfect stooge for writers who reckon that the terrorism of the anarchists and the terrorism of the Islamicists are one terror. Not included in this terror are the slave labor camps of the French and the British, the bombs, trenches, poison gas, missiles, white potassium, napalm and other of the ordinary paraphernalia of policing situations. There is no connection made between oppression and terrorism. Except to say that those who point out the oppression are justifying the terrorism

And to say back: those who are pointing out the terrorism are justifying the oppression. Flip the coin: on both sides, there’s faces.

8.

There are so many perspectives, infinite perspectives, in which a person can be seen, and the sum of these is a difficulty for novelist, policeman, anarchist, artist and the angels of God. Even those celestial recorders with their data. What does it profit an angel if they mark down a theft and lose their own souls?. Was Duval the anti-Papillon, the avenger even in chains? Paul Mimande, a journalist, went to Guyane in 1894 and wrote a reportage: Among the anarchist felons. As a senior convict, Duval was a mentor to many of those sent to the prison camps as the French Republic cracked down on political dissent. Mimande went and interviewed certain names that had once seemed threats to the bourgeois order. Duval was living, then, on one of the island camps, in a hut. He’d returned to his old job as locksmith. When Mimande asked his police guide about Duval, he was told that he no longer had the “hand” of a good locksmith, but: “… he is full of good will, no transferee is as submissive, as gentle, as well behaved.”

Mimande found that Duval had not lost his convictions. Which bored the journalist-tourist. So he asked about his wife, the family from which he had been parted, and got a satisfactory breakdown, tears, some ragged regrets about his wife. Mimande was satisfied.

Mimande’s account is of a different Duval than the one who penned the memoirs. Far from being submissive, Duval made 18 attempts to escape and he aided in a failed rebellion. He finally did escape in 1901. His memoirs, which recount his life in Guyana among the political prisoners, don’t give the details of that escape. Duval did not think of himself as an adventurer. He was an avenger.

9.

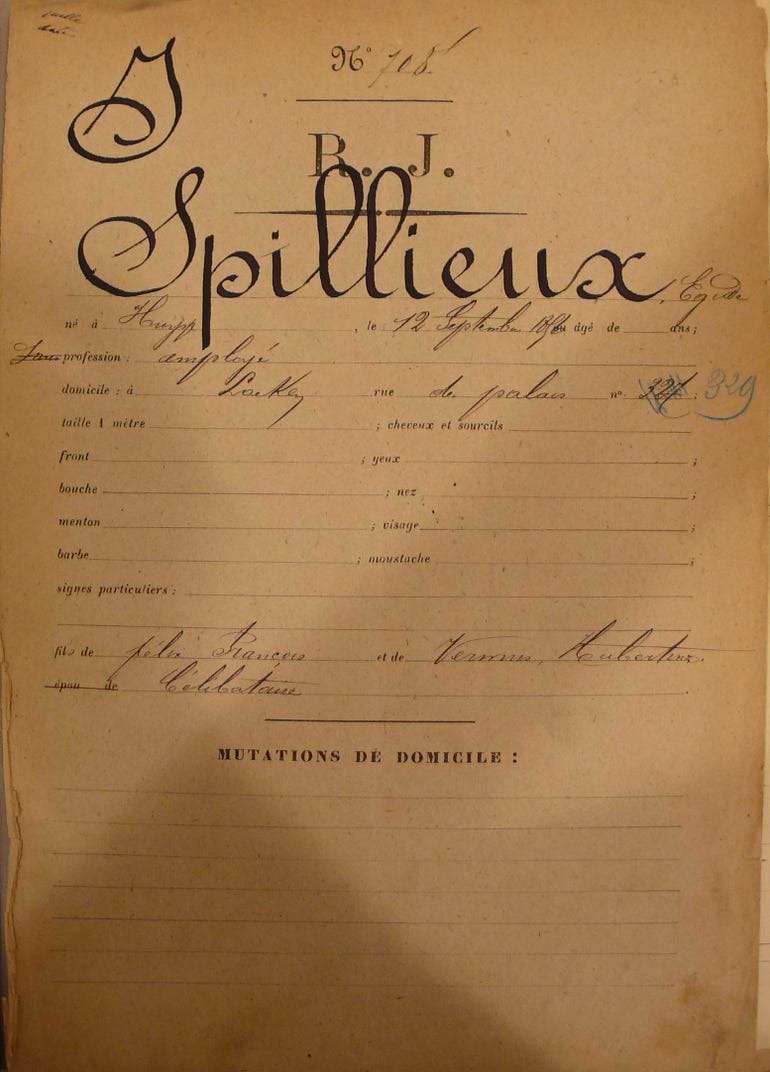

Among the anarchists, from the very beginning, there were agents provocateurs. Agent provocateurs, either hired by the cops or by the wealthy, were scattered among anarchists groups like a cluster of raisons in a pain aux raisons. The first French anarchist paper, La Révolution sociale, in 1880, was founded by Égide Spilleux, who it turned out was on the payroll of the police chief, Louis Andrieux. Duval would surely have known this. Spilleux was unmasked in 1881.

In the Affaire Duval, there is a mysterious gap, from the beginning. Duval, when he was caught, spoke of one Turquais. Or Turquet. “I met him boulevard de la Chapelle. I initiated him into anarchism. I showed him our newspapers, which are made by workers and not journalists. And then he indicated to me a good job. (with the voice of a villain in a melodrama) The day came at last to break open the strong boxes of the rich! (general hilarity).”

Another version: “I was out of work last September. My boss, to whom I had been denounced as a member of the anarchist group, the Panther of Batignolles, threw me out on the pavement. One day, in the square of Villette, I came upon Turquet sitting on a bench, not less desperate than me. We spoke of social injustice, and I showed him that it was time for anarchists to act against the propertied class. I told him that I had fabricated a jimmy for stealing, hoping by this example to give courage to the workers, who will not be free until they have blown open the safes of their bosses. It is Turquet who proposed that we rob Madame Lemaire.”

Duval did not disclaim the idea behind his crime; but his forging of a “pince” a burglar’s tool for forcing open locked drawers was as far as he had gotten. He was a talker, Duval. He wanted to “teach” the working man. Hypothesis: this is the very type of gull that the agent provocateur preys on.

Turquet knew of Madame Lemaire. How? This uncaught presence knew a place. Don’t they always? It was Turquet who shimmied over a wall, and let Duval in to the garden of the apartment. Turquet, when they got to Suzanne Lemaire’s room, the daughter of the painter, read her letters and scattered them on the carpet. They must have gone through the atelier. They must have recognized it as such. A place of work. Turquet set fire to the house, the latter over Duval’s objections. Not that Duval was against the arson for bourgeois reasons! Duval does not come out and say it, but he evidently thought arson would endanger the other people in the town house. The Judge and prosecutor laughed at Duval’s claims. Where was this Turquet? The police could not find him. Although Duval never expressed this, either at the trial or in his memoirs, there is something funny about Turquet, something that bothered Duval enough that, even though he took on himself the guilt, or the glory of the burglary, he compulsively told on Turquet. Even as he exculpated the two others who were on trial with him.

Was there really a Turquet? Was Turquet, the man conveniently on that bench, really… an agent provocateur?

Duval’s testimony, as it is reported in the different papers, makes for a slightly confused transcript, since different reporters hear different things. One collates, one gets a broad picture from the stories. But the overall tone of the courtroom is pretty clear, with the President of the court and the prosecutor either sneering or indignant, and Duval acting as he must have imagined he would act, if given a chance: as though he were turning his deed back into words, words that would penetrate the hard of hearing bourgeois world — as well as reaching the masses. He was there to testify, to tell a story, to make a courtroom procedure about a crime into a agit-prop drama about a person. The courtroom was where he could testify about his own existence; for him, the judge, the partial and stooge like “President”, was a kind of prop bourgeois in a scenario he and his anarchist group knew well.

Knew as a caricature. In the same way they were known by the judge, the reporters, the middle class readers, as caricatures. Caricature faces caricature. On both sides, there’s faces. He was proud of stealing, but never showed that he was an egotist about it, a disciple of Stirner. It was a deed clearly led to by the logic of anarchism, but it was a deed that was, primarily, for anarchism. He was clear that he was not stealing for his wife and family. In previous seasons of poverty, he had stolen a crust of bread, vegetables to feed himself and his wife, but these were not anarchist thefts. The robbery of 31 Rue Monceau was for money to fund the cause. It was for weapons, it was for printing presses. Which makes it all the more puzzling that he would try to hide his tracks through a fire, and all the more plausible that this really was not his idea.

Even at the time, even among sympathizers like the group that published Cry of the People, there were discussions of Duval’s individualist expropriation. Wasn’t theft itself always theft? If property was theft, that doesn’t mean one was therefore, justified in stealing property. Or was this to continue the chain of (socially evil) being. The mirror doesn’t destroy the room it reflects, it simply reflects it as another piece of furniture.

10.

Duval was asked if he knew Madam Lemaire. “No. But Mme. Lemaire is part of the collectivity of parasites which gnaw the worker and nourish themselves on their sweat, so I accepted to do the job. I must add that if I had known there was no money rue de Monceau, I would never have gone.”

According to many sources, Clément Duval escaped from the prison colony of Guyana on April 14, 1901.

Meanwhile, Madam Lemaire had settled back into her routine. Her work as an artist. Dumas fils, author of Lady of the Camillas, said Lemaire was, next to God, the greatest maker of roses. She provided illustrations for many books — including a thin, highly aesthetic book entitled Les Plaisirs et les jours. A book that caused an incident. Jean Lorrain, a self-consciously decadent writer, reviewed that book under the pseudonym Raitif de la Bretonne, and criticized not only the author, but the illustrator.

“Les Plaisirs et les Jours : serious melancholies, elegiac spinelessness… inane flirting with a precious and pretentious style, with, between the margins or at the head of the chapters, the flowers of Mme Lemaire as strewn symbols — and one of these chapters is called: the death of Baldassare de Silvande, le vicomte de Silvande. Illustration: two jugs. Another, Violante or the mondaine lifestyle. Illustration: two rose leaves (I’m not making this up). The ingeniousness of Mme Lemaire has never been so tightly adapted to the talent of the author… It is thus that a story entitled Amis: Octavian and Fabrice has for its commentary two cats playing the guitar …”

Jean Lorrain’s article goes on in this fashion, and even implied various things about the author’s supposed homosexual liaison with Lucien Daudet. If true, perhaps the rumor had travelled in the same gay circles as Lorrain, a very gay man. In any case, the author replied by challenging Lorrain to a duel.

Each shot twice at the other in the Bois de Meudon. None of the four bullets struck flesh. They both stood there and, one supposes, looked at each other, critic to author, with the author feeling justified and masculinely restored.

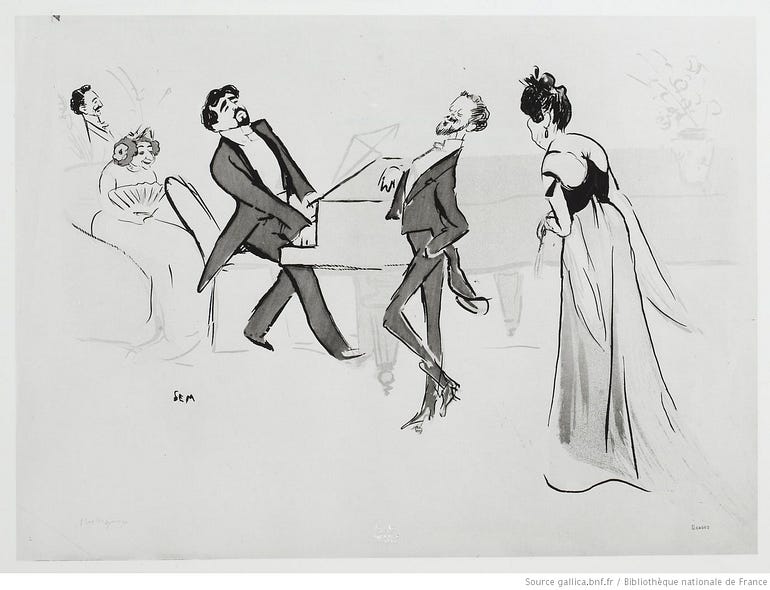

On May 11, 1903, a certain Dominique, the pseudonym of the author of Les plaisirs et les jours, wrote a floral article, Le cours aux lilas et l’atelier aux roses, subtitled “The Salon of Madame Madeleine Lemaire” for the Figaro. Was Duval already in New York at this point? The robbery of 31 Rue de Monceau had long been overshadowed by other, more drastic, anarchist deeds. Dominique made no mention of it. Dominique — or, to use his real name, Marcel Proust — was a regular at Madam Lemaire’s soirees. Her name figures extensively in his correspondence, notably with another regular, Reynaldo Hahn. Proust once wrote Hahn that after his Mama, he loved Hahn best. Hahn was a well known pianist, song-writer, and musical impresario. Between Proust and Hahn, in their letters, Madam Lemaire was gently mocked. Later, not so gently mocked, she inspired, in part, Madam Verdurin, with her “mincing tyranny.” Her way of ruling the “little clan” on her Tuesdays. Where Odette met, in an encounter whose modulated shock resonates throughout Proust’s novel, M. Swann.

11.

In Jean-Yves Tadié’s biography of Marcel Proust, Madeleine Lemaire is given the kind of shorthand biography that is allotted to the walk-on parts: the pupil of her aunt, Mme Herbeline — who owned the townhouse at 31 rue de Monceau — “a classical talent, secondary but varied” — friend of “tout Paris”. According to Martin Battersby in The World of Art Nouveau, where she engrosses a whole chapter along with a rival flower painter, Louise Abbama, she was accorded the title of Professor at The Museum of Natural History in Paris. Not that Battersby’s judgment of Lemaire’s work is unabashedly positive. He rounds up his chapter with this paragraph:

“Very few of these women painters achieved more than a mediocre standard and one of the more onerous duties of critics was to attend the annual “Salon des Femmes Peintres’ which had been inaugurated in 1881. ‘They would be better employed in devoting themselves to embroidery’, sighed one critic, but there is no use in telling them — they will do it.”

12.

Dominique’s account of Madame Lemaire begins with a pastiche of Balzac that one can’t imagine a society columnist getting away with today. We begin with the neighborhood, and come upon a certain disturbance in the street order:

“… a small townhouse which, contemptuous of all wayfare regulations, advances by a foot and a half on the sidewalk, which thus renders the street hardly wide enough to park cars on…”

The house, for Dominique, still writing under the guise of imitating Balzac, is a symbol for the painter and hostess who lives in it, for it “stops the passerby.” “One senses immediately that its proprietor must be one of those strangely powerful personages, before the caprices or habits of whom all powers must bend, for whom the ordonnances of the Prefecture of the Police and the decisions of the municipal council remain dead letters.”

The strange power that puts at naught the state, or its representatives. One wonders: is this what Duval saw? Did he and his friend Turquet “case” the joint?

Proust at this point was exploring the mysteries of different levels and forms of power — that of literature, that of the society hostess and that of her guest, that of the aristocracy and that of the bourgeois parvenu. As he wrote to Jacques Riviere, he constructed his novel on “many planes”. It is at one of Lemaire’s Tuesdays that Proust met Robert de Montesquieu, who became as important for Proust the novelist (the “model” for Baron de Charlus) as Oliver St. John Gogarty was for Joyce the novelist (the “model” of Buck Mulligan). Thus, from the atelier and salon of 31 Rue de Monceau sprang two of the great figures in A la recherche du temps perdus.

An address is an encounter. An event — which is the form taken by encounters, and which is, at the same time, irreducible to them.

And in the assault on 31 Rue de Monceau, Clément Duval made his mark on history — history as faits divers, history of little people — for which he paid with his remaining life.

13.

Posing. As regards posing. There’s a passage about the Verdurin salon. Swann comes in looking for Odette. She isn’t there. He leaves. The little clan discusses Swann — that mover between spheres, that man who is, although the Verdurin don’t know it, a personal friend of the Prince of Wales. There is some discussion about if there is something “going on” between Swann and Odette. Monsieur Verdurin remarks that even if there was, the little clan wouldn’t know about it, because it would be a matter between the two people involved.

“She would have told me,” answered Mme Verdurin with pride. “I may say that she tells me everything. As she has no one else at present. I told her that she ought to sleep with him. She makes out that the can’t; she admits, she was immensely attracted to him at first; but he’s always shy with her, and that makes her shy with him. Besides, she doesn’t care for him in that way…”

“You’ll permit me not to be of your opinion,” said M. Verdurin, “he is only half on my good side, this gentleman, and I find him a poser.”

‘Mme Verdurin stiffened, put on an inert expression, as if she were becoming a statue, a fiction that permitted her to seem like she had not heard that insupportable word, poser, which had the air of implying that one could “pose” with them, thus that one was “more than them.””

To pose. To pose in a courtroom or a salon. A salon that, once infected with the suspicion of the poser, might well erode the mysterious power it held, might dissolve the little clan. A suspicion held off by posing — posing as a statue.

Just as a too radical emphasis on the pose one held as the accused might make it seem all too arbitrary whether one was the accused or the accuser, the judge or the avenger.

14.

« Princesse, I am not going to speak to you about the war. I have, alas! Assimilated it so completely that I cannot isolate it, I can no longer speak of the hopes and fears it inspires in me than one can speak of sentiments that one experiences so profoundly that they no longer can be distinguished from oneself. It is less for me an object (in the philosophical sense of the word) than a substance interposed between me and the objects. As one loves in God, I see in the war (you know those neuralgias that one does not cease to feel as one speaks of other things, and even while one sleeps).” Proust, letter to madame Dimitri Soutzo, April, 1918.

Proust was not alone to “see” in war — this became the twentieth century experience, but he was aware of this as few of his contemporaries were.

The world after the war was tough on the world of the Verdurins. New fashions, new morals, new people, new money. It was, as well, tough on the utopias that drove the anarchists. Instead of the stateless future, the future of the collapse of the capitalist class, the future of mutual aid, utopia gravitated to the Bolsheviks.

Paul Avrich interviewed an anarchist named Florence Rossi in Needham Massachusetts on February 14, 1988. The anarchist comrades in Needham were recruited, as in many Massachusetts communities, from the Italian immigrant community. Rossi, along with her partner, Raffaele Schiavina (aka “Bruno”) were editors of L’Adunta dei Refrattari, the “principle Italian anarchist paper in the United States from the 1920s through the 1960s”.

“Clemente Duval lived with us for a while before his death. He had been living with a shoemaker in Brooklyn named Olivieri, but his house was next to the subway and Nonno — that’s what we called Duval — couldn’t sleep. So we moved to Brooklyn from New Jersey and he moved in with us. He was small, old and disfigured from arthritis. But he exercised every morning and a French comrade, Dr. Guilhempe, used to come to examine him. The neighbors thought he was Bruno’s father. He lived with us for a few months. He felt he was going to die and didn’t want to cause use any trouble, so he returned to Olivieri, where he died two days later.”

From Duval’s pamphlet, quoted in his memoir:

“And do you think that a worker with unselfish, noble sentiments can see this picture of human life constantly unroll before his eyes without revolting against it? He who feels all its effects and who is constantly its victim, morally, physically, and materially; he whom they take at twenty years old to pay the blood tax, to use his flesh against bullets to defend the properties and privileges of his masters; and he comes back from this slaughter crippled by it or with a sickness that makes him half-disabled, that makes him roll from hospital to hospital, using his flesh for the experiments of the Gentlemen of Science. I know what I’m talking about: I came back from this carnage with two wounds and rheumatism, sicknesses that have already earned me four years in the hospital and that prevent me from working six months of the year.”

Life sentences, that is what we rebel against. And the sentence keeps winning.

Madeleine Lemaire — the Patronne, or Boss, to her coterie, a bourgeois parasite to a thirty year old Clément Duval, someone he mysteriously knew of to the mysterious Turquet — died in 1928. Aux écoutes, a scandal sheet — Eavesdropper would be a good translation — published a very mean spirited obsequy, like some sort of monologue by Baron de Charlus: The Empress of roses.

Here’s how the obsequy ends:

“A sincere artist whose inspirations were without doubt limited, but with a perfect sensibility, Madeleine Lemaire suffered, and horribly, from the sort of disdain that had fallen on her painting. In these last years she received, to finish her off, two cruel blows to the heart. The first before the Nympheas of Claude Monet, which she could not understand, posing this tormenting question to her spirit: Aren’t my flowers as good as the flowers of Giverny? The second blow by an afternoon at the Salle Drouot [an auction house], They were selling a collection in which figured many Madeleine Lemaires. She wanted to know “how much that would bring in”.

The most beautiful, an immense aquarelle, sold for 150 francs. And the artist went out, her eyes humid, feeling that she was finished, that fate had shot its arrow and she was now obsolete…”

Or, as Duval might put it, once bourgeois society has no more use for you, they throw you away like a used rag.

Proust’s Madam Verdurin, in Time Rediscovered, marries twice after the death of her husband, each one bringing her higher into the social circles she so envied and derided in her own little clan. In Proust’s novel, Elstir — that representative of modern art, Monet and Manet in one — is far from being a stranger to the Verdurins. But he leaves that circle when Madam Verdurin interferes too much in his private life.

This is what Proust writes about the death of Monsieur Verdurin. “For every death is for others a simplification of existence, takes away the scruple of having to show one’s gratitude, the obligation to visit. It is in no other way that the death of M. Verdurin was received by Elstir.”

What Proust didn’t imagine was the evaporation of all these scruples before Madam Verdurin’s death, the cold hard marking down of her work in some auction hall, and her afterlife as merely the key to a certain character in a famous novel.

Or did he?

“As one loves in God, I see in the war…”

No comments:

Post a Comment