About Reason and the Imagination – let’s begin with the beginning image, or similitude, in the essay. It is an overdetermined one – the similitude between the map, which is what the utilitarians go by, versus the picture, or the globe versus the local. Of course, maps are not neutral things:

“They [the theorists] had better confine their studies to the celestial sphere and the signs of the zodiac; for there they will meet with no petty details to boggle at, or contradict their vague conclusions. Such persons would make excellent theologians, but are very indifferent philosophers. To pursue this geographical reasoning a little farther. – They may say that the map of a country or shire for instance is too large and conveys a disproportionate idea of its relation to the whole. And we say that their map of the globe is too small, and conveys no idea of it at all.”

Given these images, one might expect a defense of the local, imagination, against the universal, or reason. Which is why Hazlitt’s moral examples are so interesting – because they are not local. They are not British. They are colonial. In this, Hazlitt is following the Burkian machinery, one in which the sublime and the notion of delight play a key role, that always finds reason in images and images in reason, and that was most at work in the impeachment of Hastings and in the denunciation of the French Revolution. The local, for Burke, was founded on local traditions – and the universal was founded on respecting tradition. Go to the end of this logic and you come to the end of empire – but Burke himself did not find that the egress he sought. Instead, his thought envisions empire as a collusion among elites, which, in fact, was a definite aspect of the British rule in India and elsewhere during the 19th century. Yet Burke’s imagery is more extreme, more suggestive, than this outcome would suggest. It presents, perhaps, a surreptitious ideology, an unconscious one, which is why it is so exciting to read, for instance, Burke’s comment to one of his critical correspondents during the Hastings impeachment, Mary Palmer:

“I have no party in this business, my dear Miss Palmer, but among a set of people, who have none of your lilies and roses in their faces; but who are the images of the Great Pattern as well as you and I. I know what I am doing; whether the white people like it or not.”

Hazlitt is also in pursuit of the Great Pattern, and thinks, contra Burke, that it revealed itself in the French Revolution – taking that to span the time from 1789 to 1815, as Hazlitt does – and that the post 1815 radicalism that he tried to influence has turned towards mere patterning, towards calculations based on self interest in which the self’s intrinsic, internal interest in the self is left out of account. And he is especially wary of the fact that once the self is evacuated, the population of selves can become subject to tests – we can test out policy on them. Javed Majeed, in an essay on James Mill’s attitude towards India which were put into his history of India – one of Hazlitt’s objects of scorn in the Reason and Imagination essay – writes this, in defense of Mill’s feelings concerning empire:

“Furthermore, the tensions in James Mill’s project stem from his ambivalent stance on empire. On the one hand, Mill took an economic view of imperialism in India and argued that the expense of government, administration and wars meant that Britain had not derived any economic benefits from India. In his economic writings, he denied the importance of colonies as markets and stressed that they did not yield any economic benefits. He also argued that colonies served as a source of power and patronage for the ruling elite and were used to perpetuate their position. But Mill’s History was divided between this negative view of contemporary imperialism and the possibilities that empire opened up as the testing ground for new bodies of thought which had emerged in the metropolis and which had as their aim the critique and reform of the establishment in Britain itself.” (Javed Majeed in Utilitarianism and Empire, 96)

At this point, LI has to loop back to our own self.

Years ago, in the bitterly poor winter of 2002, LI did a series of posts about Fitzjames Stephen. At that time, we were still suffering from the afteraffects of the Tech boom delusion, i.e. we were busy trying to make it as a freelance writer. Of the idiotic detours we have taken on the way to the grave, none, none has been as shamefully stupid. Hence, the bitter poverty – there is nothing like gnawing on the bone of your own failure to leave that taste of narcissism gone sour in your saliva. Ah, but we have spent the decade since mumbling that bone! In any case, the point of my 2002 series was to illustrate a thesis, which went like this:

1. in the cold war, a historical myth was coaxed into being by conservative intellectuals;

2. the myth went like this: the whole idea of the managed economy had come, by way of crazy Frenchman, Marx, and that Lucifer, Lenin, from the Soviet Union;

3. so that the idea of managing the economy, which was all the rage among the post-war technocrats, was tainted with the Gulag.

I believed these ideas were bogus. The text that codified this bogosity was Hayek’s Road to Serfdom, with the scary, Russo-suggestive Serf in the title, and Hayek’s unconscious parody of Artaud – the plague came from the East! Instead, the whole of the British imperial enterprise in the nineteenth century, especially the governing of India, was the actual locus of the idea that the state, with the proper technostructure, could manage a society. India’s laws were changed to meet an ideal created by the utilitarianists. Property rights were transformed, the rural economy was monetized, and the sub-continent, in British eyes, bloomed. Of course, British eyes did not see wave after wave of famine; they saw railroads and exports. Such success in setting the rules of the game, under the regime of free trade, made various Indian office intellectuals, and those with whom they were connected, begin to wonder if rational administration couldn’t make capitalism itself more efficient. This idea was divided between the right – Stephen being the first to introduce a colonial authoritarianism back into conservative thinking about governing the home country – and the left, all those Fabians who shuttled back and forth between position papers and jobs in Colonial office.

At the time I was putting this thesis together, I was unaware that large parts of this had already been said before, by Eric Stokes, in his The English Utilitarians in India (1959). I did eventually peruse Stokes, but I didn’t quite get him.

Well, those are our back pages. Useless to burrow back there into the warren of our burrows. I like to think of LI as a sort of roadkill of the Bush era, emitting not just the smell of the dead, but creamed in precisely such a way that one can infer the traffic that ran us over.

In any case, resurrecting my history here, Hazlitt – at the time – did not strike me as the dialogue partner that an anti-imperialist liberalism should take up. Now he does. Which gets us to Hazlitt and the slave trade … that I have still another poky post to go over.

“I’m so bored. I hate my life.” - Britney Spears

Das Langweilige ist interessant geworden, weil das Interessante angefangen hat langweilig zu werden. – Thomas Mann

"Never for money/always for love" - The Talking Heads

Monday, January 14, 2008

Promoting my academia column in the Austin American Statesman

I was editing away today on a dissertation {and I'm looking for more editing, please!) and forgot that I was supposed to be all about me today. Me, as in I, as in not-you, as in my column in the Austin Statesman on two books: Trying Leviathan by D. Graham Burnett and Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison's groovy Zone book, Objectivity. This is my second column so far, my dearest and nearest, and I'm looking to franchise this baby - gonna send it around to various newspapers in various high ed towns and offer it for peanuts - that is, a week after the statesman publishes it. I'm not sure if this will work, but I'm gonna give it a shot. And if it does work, I'll be your man on the university press beat.

So, did I say Me? Yes. This has been shameless self promotion on the part of LI. Check it out!

PS - here's my editor Jeff's blog post about this.

So, did I say Me? Yes. This has been shameless self promotion on the part of LI. Check it out!

PS - here's my editor Jeff's blog post about this.

Sunday, January 13, 2008

Carry on you wayward son and other great lines of poetry

Obviously, the place to go on the intertubes today is the Werepoet’s site for the close reading of one of those masterpieces that justify all the effort humankind made 2 million years ago to stand up on its hind legs, to wit: Starship’s We built this city on Rock n Roll. George Saunders, eat your heart out.

Saturday, January 12, 2008

Hazlitt and the claims of the imagination

Both in Hazlitt’s essay, Reason and Imagination, and in the Spirit of the Age essay on Bentham, Hazlitt’s argument against utilitarianism proceeds on two levels.

The first level is, so to speak, a defense of the moral integrity of the person that rests on construing the imagination as having a major shaping role in creating the person. On this level, Hazlitt is not just defending the imagination as an instrument of practical reason, but he is making a larger, cultural claim against utilitarianism, which is that utilitarianism does a manifest harm to humans by diminishing their imaginative capacity. Philosophers are more used to the first line of argument than the second, if you take Hazlitt to be using the imagination to play a role similar to Hegel’s recognition. According to David Bromwich, in Hazlitt’s major and little read philosophical treatise, Essay on the Principles of Human Action, he ‘puts forward a single main thesis about the nature of action. It includes, however, distinct arguments on the limits of identity and the freedom of the imagination. The idea of a personal identityt that contiues from past to future is first shown to be an artifice – the past, says Hazlitt, is known thorugh memory, the present through consciousness. We are then asked to realize that we contemplate the future only with the help of imagination. It follows that someone else’s future is potentially as real to me as my own. Since imagination is not limited by identity, and identity itself is discontinuous, the two arguments can be shown to assist each other.”(p.18, Metaphysical Hazlitt)

It is Hazlitt’s cultural argument that, I think, gives us the more original, and even prophetic, insight. However, it is one that has been neglected or misunderstood by liberal moralists, who tend to transcribe this thesis, when they meet it, as meaning that art (which is where they take the imagination to be lodged) has some social use. But Hazlitt is not lodging the imagination in art alone – it is, rather, intrinsic to the very circle of the human. Thus, its squeezing, its distortion, by a utilitarian society is a mutilation on all persons.

It is easy not to see what Hazlitt is getting at here because his case doesn’t break along the usual fracture lines – the happiness of the greatest number vs. the universals of duty. Unlike Bentham, Hazlitt contends that the imagination inevitably intervenes on any calculation having to do with action, since the very basis of that calculation is the imaginative power that allows us to project ourselves into the future. It is thus more primary than the hedonic motive. On the other hand, unlike Kant, Hazlitt is not subscribing here to the early modern psychology that would neatly separate reason from the sensual. Kant, of course, has tried to purify his psychology of the moral terms that overlay the discourse of the affections in order to give us a pure opposition between sensual motive and the motive of reason, but the options still follow the mold of the older bias. And, indeed, that bias has not exhausted itself. The idea that the emotions and moods are ultimately reducible to pleasure and pain, to some pure animal state, is still alive in psychology – thus, happiness is a sort of cloud around a central pleasure, sadness a cloud around a central pain, and so on. In a sense, these are the masks of god – the god of pleasure assumes the mask of happiness, or enthusiasm, or excitement, the god of pain assumes the mask of anger, or of disappointment, and so on. But what shapes these masks, and what are they themselves made of?

All of which I will discuss in another post. The next post, though, will be about the second level of Hazlitt’s attack. Hazlitt’s set of examples when he attacks the utilitarians invariably stray to extra-European – to imperial – instances. The slave trade. India. And for good reason, since the utilitarians flourished in the imperial interface.

Thursday, January 10, 2008

Tears again

It kills me. It kills me. In Don Delillo’s Underworld, he has Lenny Bruce giving a performance during the Cuban Missile crisis about JFK’s speech on TV, and he says:

"Kennedy makes an appearance in public and you hear people say, I saw his hair! Or, I saw his teeth! The spectacle's so dazzling they can't take it all in. I saw his hair! They're venerating the sacred relics while the guy's still alive."

And he punctuates his monologue with a “line he’s come to love: we’re all gonna die!”

That was back when superman first came to the supermarket. The monster was just being born back then, and it didn’t seem at all like a monster, it seemed like art: those Esquire writers, like Norman Mailer, going beyond the surface scrim of politics to contact with knowing fingers the Siamese twin tie between the larger than life personality and the larger life at large, the semiotic encoded in the statesman’s gestures, his suits, his dislike of hats… And so this new way of writing about politicos, writing about them as though they were characters in a novel, was born. Born just as the novel was dying out as a dominant aesthetic form – cut out the middleman, make your own in living breathing flesh and blood characters, hire consultants to do it, and then raise up a brood of commentors whose perceptions are as predictably shallow as their upbringing, a background in which was omitted all history, languages, nights of the soul, empathy, imagination, knowledge, and loose this whole dire bestiary on tv and in the papers as a permanent chorus, giving us ever thinner narratives, novels in which Superman gradually lost the irony and became an action movie figure, President Mission Accomplished, and in which now the emphasis was all on the hair, the cleavage, the tears – because this brood weaves novels that will never reflect the sad state of our prosperous days. These are the days when democracy is giving birth to feudalism, to syndromes ong thought to be long extinct – mercenary armies, torture, an executive claiming more divine rights than Charles I ever dreamed of. Accompanying it is the slugs orgy of outrage 24/7, the cretinorama by which all the information by which one could make an informed choice about anything – drugs, cars, toothpaste, politicians – is utterly waylaid in a maze. As our lords and masters intended it to be – make the world hazy and issue credit cards, that’s the plan.

The continuing ‘controversy’ about Hillary Clinton’s tears hurts so bad it is going to make my balls drop off. Nobody gives a flying fuck, except in TV toyland. Oh, it isn’t that sentimentality and mushiness should be off the radar as far as politics is concerned. I propose we do talk about it. I say, let’s talk about the worst, the bloodiest, the most malign sentimentality of them all, which is called toughness. It is the silence the boy substitutes for calling for his mommy. And soon it hardens delightfully over the tyke. Oh how they love toughness, the media Heathers, oh how it makes them cum cum cum all over their peashooters. Of course, the funny thing is that the toughness they sentimentalize about is projected on such amazing, bilious old physical wrecks like Fred Thompson or John McCain. On the other hand, the Ur-gesture of toughness – going into a convenience store and blow the head off the cashier, for instance – is all too yucky. Oh, that scares them so much that they desire even tougher men to lock those tough boys up. So it is tough and tougher, a simp’s progress down the road to the pit. And all that fucked up toughness is unmoored. It is part and parcel of the whole unmoored emotional landscape that has to float above the wasteland created by the corporation and the state, it’s a clip joint sentimentality designed to get men and women down down down on the totem pole to look up and admire, as their heroes, the men and women who systematically plunder them, who contrive their vulnerability, who pride themselves on gambling with the lives of the feebs’ and rubes’ children. They are tough, those who build, cell by carcinogenic cell, the environment of disaster into which we are collectively drifting.

"Kennedy makes an appearance in public and you hear people say, I saw his hair! Or, I saw his teeth! The spectacle's so dazzling they can't take it all in. I saw his hair! They're venerating the sacred relics while the guy's still alive."

And he punctuates his monologue with a “line he’s come to love: we’re all gonna die!”

That was back when superman first came to the supermarket. The monster was just being born back then, and it didn’t seem at all like a monster, it seemed like art: those Esquire writers, like Norman Mailer, going beyond the surface scrim of politics to contact with knowing fingers the Siamese twin tie between the larger than life personality and the larger life at large, the semiotic encoded in the statesman’s gestures, his suits, his dislike of hats… And so this new way of writing about politicos, writing about them as though they were characters in a novel, was born. Born just as the novel was dying out as a dominant aesthetic form – cut out the middleman, make your own in living breathing flesh and blood characters, hire consultants to do it, and then raise up a brood of commentors whose perceptions are as predictably shallow as their upbringing, a background in which was omitted all history, languages, nights of the soul, empathy, imagination, knowledge, and loose this whole dire bestiary on tv and in the papers as a permanent chorus, giving us ever thinner narratives, novels in which Superman gradually lost the irony and became an action movie figure, President Mission Accomplished, and in which now the emphasis was all on the hair, the cleavage, the tears – because this brood weaves novels that will never reflect the sad state of our prosperous days. These are the days when democracy is giving birth to feudalism, to syndromes ong thought to be long extinct – mercenary armies, torture, an executive claiming more divine rights than Charles I ever dreamed of. Accompanying it is the slugs orgy of outrage 24/7, the cretinorama by which all the information by which one could make an informed choice about anything – drugs, cars, toothpaste, politicians – is utterly waylaid in a maze. As our lords and masters intended it to be – make the world hazy and issue credit cards, that’s the plan.

The continuing ‘controversy’ about Hillary Clinton’s tears hurts so bad it is going to make my balls drop off. Nobody gives a flying fuck, except in TV toyland. Oh, it isn’t that sentimentality and mushiness should be off the radar as far as politics is concerned. I propose we do talk about it. I say, let’s talk about the worst, the bloodiest, the most malign sentimentality of them all, which is called toughness. It is the silence the boy substitutes for calling for his mommy. And soon it hardens delightfully over the tyke. Oh how they love toughness, the media Heathers, oh how it makes them cum cum cum all over their peashooters. Of course, the funny thing is that the toughness they sentimentalize about is projected on such amazing, bilious old physical wrecks like Fred Thompson or John McCain. On the other hand, the Ur-gesture of toughness – going into a convenience store and blow the head off the cashier, for instance – is all too yucky. Oh, that scares them so much that they desire even tougher men to lock those tough boys up. So it is tough and tougher, a simp’s progress down the road to the pit. And all that fucked up toughness is unmoored. It is part and parcel of the whole unmoored emotional landscape that has to float above the wasteland created by the corporation and the state, it’s a clip joint sentimentality designed to get men and women down down down on the totem pole to look up and admire, as their heroes, the men and women who systematically plunder them, who contrive their vulnerability, who pride themselves on gambling with the lives of the feebs’ and rubes’ children. They are tough, those who build, cell by carcinogenic cell, the environment of disaster into which we are collectively drifting.

Wednesday, January 09, 2008

Magic, zombies, the NH primary

Ah, the old dilemma. On the one hand, the Clintons represent the vilest D.C. shit imaginable – war, neo-liberalism, faux progressive politics that gets up in your ass and eats your intestine. And just as you are about to throw them out, they get attacked by – the even viler people. The media krewe of nitwits and combjobs who, over the last week, danced around like the high school students in Carrie, so happy that the wicked Hillary – she’s not a cheerleader girl at all! – was no longer in contention to be prom queen. The sheer overwhelming dreadful gross misogyny of it all made anybody with any heart want to strike them back, to slap those fat sleek faces until they were red. And so the 1998 white magic happens all over again. You can tell from who votes for the Clintons that it is a visceral class phenomena – that’s the sad part. It is the Blue collar belt that really always saves the Clintons bacon, not because the working class are stupid peckerwoods, but because they have a healthy animal instinct for the enemy. Although superficially they might nod along as the anchorman trills through his pack of lies, an instinct scratches. What is so sad is that, in these circumstances, the Clintons are really in the enemy camp. The enemy of my enemy is still my enemy. How fucked is that?

I was thinking, today, that someone really needs to start up the Adam Nagourney satire site again that went up in 2004 – this time, I think, as Jokeline, the popular comment thread name for Joe Klein – something that will throw as much shit as possible at the bastards. It is hard to think straight about politics when everything you hate is embodied every day on every channel and every newspaper – a smirking, brainless, sycophantic syndicate of toad eaters whose every gesture and remark is redolent of class privilege, ignorance, and such a remarkable lack of soul, such a vacuum of an interior life, such a cardboard sensibility for the normal drama of human existence that, that, that – I mean, it would shock a zombie how dead these people all are. All those stories about ‘natives’ fearing that photographs drain your soul are obviously scientifically right –for haven’t we watched TV drain the soul, down to the last drop, of those greedy talking heads that elbow their way in front of the camera? They exist solely to cretinize us – to make us stupider and stupider – on the magical principle of like drawing to like. As they draw the last bit of your soul out of fingertips, you can join them in a sort of vampire state of non-being.

So, somehow, that Clinton won – while I so ardently want Clinton to lose, to hear no more of Clinton, to see no more Clinton, somehow, somehow – this news made me smile.

I was thinking, today, that someone really needs to start up the Adam Nagourney satire site again that went up in 2004 – this time, I think, as Jokeline, the popular comment thread name for Joe Klein – something that will throw as much shit as possible at the bastards. It is hard to think straight about politics when everything you hate is embodied every day on every channel and every newspaper – a smirking, brainless, sycophantic syndicate of toad eaters whose every gesture and remark is redolent of class privilege, ignorance, and such a remarkable lack of soul, such a vacuum of an interior life, such a cardboard sensibility for the normal drama of human existence that, that, that – I mean, it would shock a zombie how dead these people all are. All those stories about ‘natives’ fearing that photographs drain your soul are obviously scientifically right –for haven’t we watched TV drain the soul, down to the last drop, of those greedy talking heads that elbow their way in front of the camera? They exist solely to cretinize us – to make us stupider and stupider – on the magical principle of like drawing to like. As they draw the last bit of your soul out of fingertips, you can join them in a sort of vampire state of non-being.

So, somehow, that Clinton won – while I so ardently want Clinton to lose, to hear no more of Clinton, to see no more Clinton, somehow, somehow – this news made me smile.

Tuesday, January 08, 2008

Alien: coming to an economic sector near you!

LI has several posts on the drawing board. We have a post about Derrida and intercessors that is partly a reply to certain things LCC has said about my man Jack; we have to complete our sequence about Hazlitt; and most of all, we want to talk about Alexander Herzen. Piqued by this recent piece in More Intelligent Life about the Moscow Inszenierung of Tom Stoppard’s play in Moscow (and, by accident, doing a lot of editing recently on papers having to do with Russian intellectual life), we started reading Herzen. Long ago, I bought a paperback abridgement of Herzen’s autobiography, and somewhere in the mounds of paper on one of my desk it is probably hibernating, its little heart slowed to a death’s breath by day after day of non-reading.

But all of those fun things are so fuckin’ convoluted, dude! Taking forever to think out and then to write. Whereas I could just refer to this excellent little Financial Times piece by Stephen Roach. Now, at least I know one of my readers – I’m looking at you, Brian! – is as into depression prediction porn as I am. There’s a vast audience out there for those books with titles like: 1980s – Coming Depression! 1990s – Great Crash! 2000 – How the coming depression will change everything! Myself, I’ve even got depressed about this coming depression. The key word seems to be coming. It is always coming, but never arriving. Hey hey, I told you it was porn, didn’t I?

In actual fact, depression (recession is of the same genre of euphemisms as Defense department is for Department of War – it was coined in the fifties to make life seem more comfy) has long ago become a sectional thing, and the Keynesian economy (which undergirds the present neo-liberal order) has gotten very good at compartmentalizing it. The Rust Belt’s depressed – the Sun Belt’s booming. Finances sag, the power market surges. The political advantage of this from the standpoint of Mr. Moneybags, your softshoeing Monopoly card capitalist, is that depression never becomes a category around which political identification can take place. Divide and conquer and all that shit.

But though we don’t think of the totality, the totality thinks of us. And this is what Roach’s article does pretty well, laying out a schema that makes sense of some everduring features in our current economic landscape:

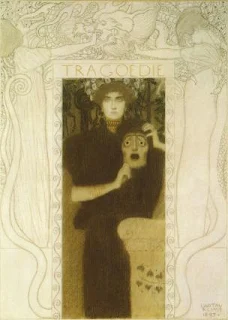

Now, there’s a little sour grapesianism going on here. Bubbles have a bad rep – and deservedly so, at least back in the Tulipomania past. Myself, I’m open to the question of whether we don’t have an affluent enough framework in which bubbles actually do a different kind of job, now – bubbles might be the thing that, in tandem with the sectoral depressions, keep the economy afloat. Much as I hate to say it, they’ve done a really good job at that. While a marginal old fart such as myself has long been among the people who are sat on by the people who are sat on by the people who are sat on in this economy, I’ve noticed much less disgruntlement among the masses about the general sitch. It might be that Roach is right – we can’t borrow any more, the bills come due, the walls of Jericho, NYC, Washingon D.C., Houston, L.A., Dallas, Atlanta and Miami fall, and we all come face to face with the face of capitalism, a picture of which I am including for your viewing pleasure here:

But forgive an old dodderer his doubts. I’ve heard this before. Maybe the years are just wearing away my resistance to being sat on. And of course Roach ends with an unjustified inference:

But all of those fun things are so fuckin’ convoluted, dude! Taking forever to think out and then to write. Whereas I could just refer to this excellent little Financial Times piece by Stephen Roach. Now, at least I know one of my readers – I’m looking at you, Brian! – is as into depression prediction porn as I am. There’s a vast audience out there for those books with titles like: 1980s – Coming Depression! 1990s – Great Crash! 2000 – How the coming depression will change everything! Myself, I’ve even got depressed about this coming depression. The key word seems to be coming. It is always coming, but never arriving. Hey hey, I told you it was porn, didn’t I?

In actual fact, depression (recession is of the same genre of euphemisms as Defense department is for Department of War – it was coined in the fifties to make life seem more comfy) has long ago become a sectional thing, and the Keynesian economy (which undergirds the present neo-liberal order) has gotten very good at compartmentalizing it. The Rust Belt’s depressed – the Sun Belt’s booming. Finances sag, the power market surges. The political advantage of this from the standpoint of Mr. Moneybags, your softshoeing Monopoly card capitalist, is that depression never becomes a category around which political identification can take place. Divide and conquer and all that shit.

But though we don’t think of the totality, the totality thinks of us. And this is what Roach’s article does pretty well, laying out a schema that makes sense of some everduring features in our current economic landscape:

“The US has been the main culprit behind the destabilising global imbalances of recent years. America’s massive current account deficit absorbs about 75 per cent of the world’s surplus saving. Most believe that a weaker US dollar is the best cure for these imbalances. Yet a broad measure of the US dollar has dropped 23 per cent since February 2002 in real terms, with only minimal impact on America’s gaping external imbalance. Dollar bears argue that more currency depreciation is needed. Protectionists insist that China – which has the largest bilateral trade imbalance with the US – should bear a disproportionate share of the next downleg in the US dollar.

There is good reason to doubt this view. America’s current account deficit is due more to bubbles in asset prices than to a misaligned dollar. A resolution will require more of a correction in asset prices than a further depreciation of the dollar. At the core of the problem is one of the most insidious characteristics of an asset-dependent economy – a chronic shortfall in domestic saving. With America’s net national saving averaging a mere 1.4 per cent of national income over the past five years, the US has had to import surplus saving from abroad to keep growing. That means it must run massive current account and trade deficits to attract the foreign capital.

America’s aversion toward saving did not appear out of thin air. Waves of asset appreciation – first equities and, more recently, residential property – convinced citizens that a new era was at hand. Reinforced by a monstrous bubble of cheap credit, there was little perceived need to save the old-fashioned way – out of income. Assets became the preferred vehicle of choice.”

Now, there’s a little sour grapesianism going on here. Bubbles have a bad rep – and deservedly so, at least back in the Tulipomania past. Myself, I’m open to the question of whether we don’t have an affluent enough framework in which bubbles actually do a different kind of job, now – bubbles might be the thing that, in tandem with the sectoral depressions, keep the economy afloat. Much as I hate to say it, they’ve done a really good job at that. While a marginal old fart such as myself has long been among the people who are sat on by the people who are sat on by the people who are sat on in this economy, I’ve noticed much less disgruntlement among the masses about the general sitch. It might be that Roach is right – we can’t borrow any more, the bills come due, the walls of Jericho, NYC, Washingon D.C., Houston, L.A., Dallas, Atlanta and Miami fall, and we all come face to face with the face of capitalism, a picture of which I am including for your viewing pleasure here:

But forgive an old dodderer his doubts. I’ve heard this before. Maybe the years are just wearing away my resistance to being sat on. And of course Roach ends with an unjustified inference:

“It is going to be a very painful process to break the addiction to asset-led behaviour. No one wants recessions, asset deflation and rising unemployment. But this has always been the potential endgame of a bubble-prone US economy. The longer America puts off this reckoning, the steeper the ultimate price of adjustment.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Love and the electric chair

It is an interesting exercise to apply the method of the theorists to themselves. For instance, Walter Benjamin, who was critiqued by Ador...

-

You can skip this boring part ... LI has not been able to keep up with Chabert in her multi-entry assault on Derrida. As in a proper duel, t...

-

Ladies and Gentlemen... the moment you have all been waiting for! An adventure beyond your wildest dreams! An adrenaline rush from start to...

-

LI feels like a little note on politics is called for. The comments thread following the dialectics of diddling post made me realize that, ...