In the lexicon of cognitive states, brooding has a

distinctly low ranking. We meditate or reflect to achieve illumination;

brooding, however, is the prelude to a tantrum. To think means trying to see

the object of thought whole – but the brooder is peculiarly averse to letting

go of the object of thought, and thus condemns himself to repetition and

compulsion. Argument is meant to persuade us to let the personal go, to, in

effect, accept the autonomy of discourse. In Socrates’ dialogues, the argument

is often treated as though it were some live thing, a spirit, a genius that

must be respected. As such, the argument is extra-personal. From this

perspective, brooding is a failed, or at the very least, a pariah cognitive

act.

Yet, the brooder does have one fierce insight on his side,

for the ideology of cognition obscures the moment of surrender, or sacrifice,

in the release of the object of thought to the drift of discourse – to “what

everybody knows”. The brooder understands that argument’s aspiration to universality

is founded on blooding the personal, and that universality operates under the

rule of polemos, or war. To surrender a thought is, among other things, to

surrender.

Cioran is one of the great brooders. His longer essays can

seem wearying because his sentences are so highly worked that they seem not to

be building an argument, but to be resisting one. The readerly flow of the

essay is impeded by the brilliances of its individual moments. Cioran sometimes

seems like one of those brilliant

conversationalists who never, actually, converse – in as much as conversation

is marked by listening, while the brilliance of the conversationalist seems

impervious to hearing. It bears the mark of a certain deafness. And so it is,

sometimes, with Cioran, especially in his first texts.

Cioran’s development of a reader is a long, painful

abdication of the harangue and the monologue. To hear the other means, in a

sense, letting your style – the verbal front Cioran is so careful to maintain –

allow itself a certain vulnerability. Cioran begins to be readable, for just

this reason, in The Temptation to Exist. It is here that he actually goes the

distance, rather than contenting himself with the pure jab of the phrase.

It is here, too, that he takes as one of his objects of

thought brooding itself – although he doesn’t label the negative space he

opposes to reflection “brooding” as such. What he does is turn upon reflection,

in its institutional forms (literature and philosophy) his suspicion that

underneath the mask of liberality lurks the spirit of resentment, the eternal

return of a grievance. This notion has a long history, and we know its avatars:

Schopenhauer and Nietzsche in particular. It is the reactionary road to

enlightenment.

In Letter on some roadblocks (Lettre sur quelques impasses),

Cioran uses a trick that he employs, as well, in later texts to detach himself

from the brooder’s solipsism: the essay as a message to some correspondent. To

write a letter is not the same as engaging in a conversation, because letters are not subject to the vital

element in conversation – interruption. While conversations go by “turns”, the

violent can bear them away simply by interrupting, and there is nothing in the

rules that forbids this. But letters are, briefly, a space the producer

controls. At the same time, the letter must, however grudgingly, acknowledge

the addressee.

The impasses or roadblocks here collect around the hated

figure of the writer. On the pretence that Cioran is warning his friend against

publishing a book, he launches into an invective against the mere writer – the

littérateur – which, of course, produces a performative “impass” - since Cioran is very much a writer. This

allots him a paradoxical place in his argument. Cioran accepts the cynicism of

the paradox – he even exploits it. It is as though he were not so much a writer

as an anthropologist carrying out fieldwork on people like Cioran – other

writers. And in this guise, he is reporting on their rituals.

What is it that Cioran hates about the writer? It is, I think, the writer’s

tendency to be a moral entrepreneur – to wave about his sensitivity to right

and wrong as though it were a superiority, a talent. Underneath the moral

entrepreneur, Cioran spots the vacuity of the rhetorician:

‘Voltaire was the first litterateur to erect his

incompetence into a procedure, a method. Before him the writer, happy enough to

be next to events, was more modest: doing his job in a limited sector, he

followed his path and stuck to it. No journalist, he was most interested in the

anecdotal aspect of certain solitudes:

his indiscretion was inefficacious.

With our know it all (hableur) things changed. None of the

subjects which intrigued his times escaped his sarcasm, his demi-science, his

need for noise, his universal vulgarity.Everything was impure with him, except

his style…”

Note a key term for Cioran: impurity. Impurity, for Cioran,

is a hallmark of liberal enlightenment. To understand this, one has to

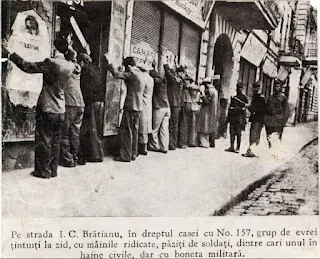

understand Cioran’s dallying with fascism of the most violent sort in the 30s,

and his brief stance as an admirer of Hitler.

This, actually, is the center of what Cioran brooded upon his whole life

long – his error, here, and his retraction. In the 30s, Cioran was very

explicit about his hatred of the Jews, his desire for war, his faith in great

and therapeutic violence that would stamp some hierarchy on the people for one

thousand years.

Later, in the late thirties in France, he began to change

his mind. He did not, as far as I am aware of, collaborate in the forties.

Rather, he went over and over the logic of his position, starting from the idea

that liberal Europe had suffocated itself under its own dead skin, exiled from

the sources of life itself. And yet, he retreated to the liberal side and renounced

violence: he renounced life-affirming war, and opted for death-affirming peace.

Violence, in Cioran’s view, makes us gigantic, larger than life, and we

renounce it at our peril. In History and Utopia he wrote:

“We employ our clearest vigils in taking apart our enemies

limb from limb, pulling out their eyes and guts, popping and emptying their

veins, crushing and pounding underfoot

each of their organs, and leaving them, for charity’s sake, merely the

enjoyment of their skeletons.” But, clearly, these are visions that Cioran now

does not want to see realized on the streets of the cities (where, as he

remarked somewhere else, he is always mildly astonished that everyone is not

killing everyone else). However, that renunciation has a price. The price is paid

in purity: “Not to venge oneself is to be enchained in the idea of forgiveness,

it is to sink into it, get stuck in it, it is to render oneself impure by the

hatred one strangles in oneself.”

Thus, the hidden dialectic between, on the one hand, the

universal vulgarisers of liberal society, and, on the other hand, the stocking

up of resentment and weakness. What distinguished the Fascist principle for

Cioran was its recognition of the logic of purity: it advocated violence not

for the sake of peace, but because violence was beautiful; bombing was

beautiful because it smashed and hurt our enemies down to the last generation;

mass murder was beautiful because you could see your true self in the pooled

blood of the victims. Cioran, at last, recognized this to be madness, but he

did not renounce the logic of purity – rather, he sought a catharsis through

rehearsing extreme statements in the paradoxical mode. After getting off to a

false start in life, he made false starts a hallmark of his style. And so

brooding, in his work, takes the place of reflection, and reflects, pallidly,

the dangerous fires that he had longed to light himself – and that then ran so

out of control that he was condemned to live in a world that was singed by the

destruction they wrought.

No comments:

Post a Comment